Rehearsing the apocalypse: Life in Kharkiv after the Ukrainian counteroffensive

"You know, Kharkiv was not awarded the title of Hero City after World War II. ["Hero City" is an honorary title awarded by the USSR in 1965-1985 to cities now in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine for their outstanding heroism during World War II - ed.] There were plenty of reasons to do so, but Moscow decided not to. But Kharkiv has earned that title now. It's difficult to single out individual heroes here.

Everyone here is a hero." Ihor Terekhov, Mayor of Kharkiv, made this rather grand statement with a somewhat disarming sincerity in a recent conversation with Ukrainska Pravda. After more than 300 days of relentless hostilities, bombardment, destruction and civilians sheltering in the city's metro [Kharkiv's system of underground trains - ed.] since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Kharkiv is truly emerging as a city that is confident, stubborn and, if you will, heroic.

This city's history might well serve as a metaphor for the rest of Ukraine, because historically, Kharkiv's biggest problem has always been its proximity to Russia. That is also the reason why the city has experienced the war relentlessly since day one, 24 February. The intensity of shelling varied, as did the distance to the front line and the numbers of Russian occupying troops on the approach to the city, but one thing remained constant: almost every day, Kharkiv has been rocked by yet more strikes.

In contrast to Kyiv, Chernihiv and even Sumy, Kharkiv is unfortunately situated only 40 kilometres away from the Russian border. That's why even when the occupiers were pushed back, the war was far from over for Kharkiv. Quite the contrary: it entered a new phase that was psychologically even more difficult than before; one that resembles scenes from apocalyptic Hollywood movies.

Top Russian authorities in the Kremlin, stuck somewhere in the 18th century, have decided to plunge Kharkiv, a modern megapolis, into that same distant past. Following their failure on the Kharkiv front, Russian forces began targeted attacks on the region's critical infrastructure, dooming millions of civilians in Kharkiv Oblast and neighbouring oblasts to a life without electricity, running water, gas, and everything that is encompassed by the phrase "modern civilisation". While Kyiv's residents spend their evenings in bars and restaurants, Kharkiv is shrouded in the impenetrable darkness of the blackout.

Yet in this darkness there are glimmers of hope: the countless stories of heroism, the search for new leaders, and tentative dreams about the city's great reconstruction in the future. Ukrainska Pravda journalists spent three days in Kharkiv in an attempt to document several of those stories, which are now presented below.

A scarred city

If you spend some time looking at the Derzhprom building in Kharkiv, it might seem that the war never happened. [This is a building in central Kharkiv known as the State Industry Building or the Palace of Industry in English. It was the first modern skyscraper in the Soviet Union upon its completion in 1928 - ed.] The pavements are swept, the grass has been cut neatly, the trees are carefully pruned.

But the moment you look back, the war becomes plainly obvious as the building of the Kharkiv Oblast Administration, destroyed by several Russian missile strikes, comes into view.

Kharkiv Oblast State Administration

Kharkiv Oblast State Administration

We met Taras Kovalchuk where the roads fork in front of the [destroyed] administration building, right where the Russian missiles landed on 1 March. Taras is a blogger and a Kharkiv native. A few weeks ago, craft beer saved his life.

Taras lives in an apartment block right next to the Kharkiv Oblast Administration building. The windows of his apartment were shattered by the shelling on 1 March. Taras put off getting started on renovations until August, when he finally decided it was time to get to work.

"I have a tradition: I celebrate my birthday elsewhere, but I always try to be in Kharkiv on Kharkiv Day, 23 August. I thought it shouldn't be any different this year, so I came here," Taras recalls. Kharkiv Day is practically his second birthday now.

Taras Kovalchuk

Taras Kovalchuk

"I was at home.

I was supposed to stay there for a while, to finish tidying things up, but my friend called me and told me to stop by [a store] and pick up something [to drink] for the night, to celebrate. I called a local craft beer shop and they told me they were only open till 7 pm and were about to close. I begged them to stay open till I got there, called a taxi and went there straight away.

Meanwhile, another missile struck this place and destroyed everything here. Again," Taras says, a smile barely visible under his moustache. "There was absolutely no logic behind that attack.

The Oblast Administration building had already been completely destroyed after the first attack, there hadn't been anyone there for a long time," he adds, pointing at the ruined heating pipes, which he had replaced just before the second missile struck, with some sadness.

At least the walls of Taras's apartment withstood the blast. His friend lived a block away from the Oblast Administration building, in a now-infamous 19th-century tenement building, photographs of which have been shared the world over. Now that building might well serve as a horror film set: the doors of a small room, with a Klimt reproduction on the wall, no longer open into another room, but into an abyss of evil and horror.

Taras says that the spokesperson for the Kraken unit, a special sabotage unit subordinated to the Main Intelligence Directorate of the Ministry of Defence of Ukraine, gave an interview in front of a building like that - and just 20 minutes later the building was hit by a Russian missile.

A local resident who was collaborating with the Russian army had helped guide the attack. This is an unsettling story: it seems that anyone walking next to us on the street could turn out to be a traitor responsible for razing one of many buildings to the ground. Meanwhile, Taras, who is giving us a "war tour" of the city, suggests that we walk several blocks from the Oblast Administration building to a local spot called Liudy (People), a basement bar.

It's a unique venue, perhaps the only one in central Kharkiv that didn't close its doors when the war started but, on the contrary, opened them. It became a cult spot as soon as it opened. You can meet people from totally different groups and demographics there: from hipsters and influencers to top government officials and military personnel.

Though only when the bar's open. When we go downstairs into the basement, total darkness closes in on us. Only the flickering light of several small candles somewhere at the back of the long narrow room breaks the darkness.

"There's another blackout in Kharkiv. The Russians have been launching missiles on the Thermoelectric Power Plant and all sorts of transformers for the past several days. Municipal workers are doing their best to restore [power], but it could take up to a day," a bartender explains sadly.

Outside, we find out that power has already been restored in the next neighbourhood over, so we decide to call a taxi and have lunch in one of the cafes or restaurants there.

This is another aspect of Kharkiv's "new normal": "power migration", meaning that you go food shopping or to dine out wherever there's still power, not where you might be used to shopping or eating. There's a sudden explosion right behind us as we wait for the taxi. Within a few seconds, another strike takes place.

At the same time, everyone's smartphones have started to sound the air-raid alarm. "Kharkiv is really close to the [Russian] border, there's not enough time to record the missiles being launched. So we get an explosion first, then the air-raid sirens," Taras explains, adding, "If we hear the siren before the explosion, it means [the missiles are] going to strike elsewhere."

The Ukrainian people wouldn't be quite themselves if they didn't get used to these new circumstances. One of the Telegram channels most popular with Kharkiv residents is maintained by an anonymous resident of a village near the Ukrainian-Russian border. Missiles launched from Russia's Belgorod Oblast [near the border with Ukraine - ed.] usually fly over his village, and he posts about it on Telegram.

This gives [the residents of Kharkiv] a few seconds or minutes before the missile destroys another residential building or industrial target. In general, the city of Kharkiv is a "scarred city", as Ihor Terekhov, the Mayor of Kharkiv, once put it. The neighbourhood of Pivnichna Saltivka has been the most badly affected by the Russian attacks, especially artillery.

But every street in central Kharkiv also bears signs of recent strikes. The war, like Godzilla in the movies, entered the city and wrecked everything in its path, tearing away the roofs of buildings, shattering windows, trampling over people's lives and fortunes. It is oblivious to the nuances of local architecture, not caring whether it destroys a modernist building on Sumska Street - the office of former Minister [of Internal Affairs] [Arsen] Avakov which has been hit by a Russian missile - or a regular apartment block in a residential district.

The only difference is the way that the residents of different neighbourhoods respond to Russian attacks.

In addition to "power migration", another, regular kind of migration is also underway. The majority of Kharkiv's residents have left the city's central neighbourhood. "Kharkiv is not a poor city.

It's usually the wealthy intelligentsia, business people, academics and so on who live in the city centre. People who had the opportunities and resources to leave - and that's what they did. If you go to neighbourhoods further away from the centre, a lot more people have stayed there than in central Kharkiv," says Roman Semenukha, Deputy Head of the Oblast Administration.

Several rockets launched from Russian multiple-launch rocket systems (MLRS) landed right next to his house in central Kharkiv a week or so ago. "We asked mobile phone service providers for information about service users. As of the end of the summer, only about 55% of the people who lived in Kharkiv before the war were still here.

Many of those who left didn't go abroad, but to neighbouring districts. If you go to nearby villages now, sooner or later you'll see an expensive Porsche or Mercedes parked next to ordinary village houses," Semenukha explains. There is also a small group of people who, instead of fleeing Kharkiv, went back there at the beginning of the war.

Vsevolod Kozhemiaka, a local businessman who was in the Swiss Alps when the war started, is one of them. Now he is the commander of the Khartiia voluntary battalion. He has recently come to the forefront of media attention because the fighters of his battalion raised a Ukrainian flag over one of the settlements near the Ukrainian-Russian border that was recently liberated in Kharkiv Oblast.

We arranged to meet Kozhemiaka, and he came to pick us up in his car. He promised to show us an "interesting Kharkiv spot". When his armoured Land Cruiser finally stopped and we got out, we realised that we were standing outside of the already familiar Liudy bar.

"We're helping them as needed - they feed the soldiers. We're friends," Kozhemiaka says, explaining his choice of where to take us. Once again, we are unable to stay for a drink.

Once again, Russian missiles had prevented Liudy from opening its doors.

Test collapse: Balakliia and Kharkiv

We are meeting Oleh Syniehubov, the Head of Kharkiv Oblast State Administration, at 8 am on a central square near the Derzhprom building. He has agreed to take us with him to Balakliia, liberated a few days before. Olena, Syniehubov's assistant, is complaining, saying that they also wanted to go to Izium, which has been completely destroyed, but the soldiers wouldn't give permission this morning.

The following day President Zelenskyy arrives in Izium and it becomes clear why we were not allowed there. Our car joins a police car and Syniehubov's black Land Cruiser, and we set off like a small "motorcade". The satnav shows the nearest route and approximate journey time - 1 hour 20 minutes.

It actually takes more than three hours one-way due to exploded bridges, damaged roads, and detours through fields or swamps.

There are only a few civilian cars on the road. It's mostly convoys of Ukrainian military vehicles, trucks towing captured Russian vehicles, and sometimes, so rarely that it is like an exotic speck, horse-drawn carts can be seen, carrying men who are weary as the land itself. We overtake a convoy of ten Ukrainian Post Office vehicles that are delivering cash for pensions and everything needed to resume operations in Balakliia.

"Approximately 30% of the oblast was occupied at first.

Now we estimate that there is approximately 10% left under occupation. But living under occupation for a month is one thing - six months is totally different. People have vastly different feelings here," Syniehubov tells Ukrainska Pravda as we walk around the central square in Balakliia.

A big group of people, mostly older people, is gathering around us, waiting for the humanitarian aid to be distributed. Syniehubov explains that the main difficulty of living under the occupation was that towns, cities and villages were without electricity, water supply, communications and [internet] connection for months on end. "But even Kharkiv is in a bad way at the moment.

I'm mostly talking about critical infrastructure facilities. The enemy targets them deliberately. The Russians are trying to hit sewage treatment facilities in Kharkiv.

This is a very bad sign. When the energy distribution substation in Kharkiv was destroyed, and there are only a couple of them in the oblast, this was a very serious attack on critical infrastructure," Syniehubov says. And what he says about Kharkiv sounds especially vivid and disturbing against the backdrop of a weary, somewhat irritated group of people waiting for humanitarian aid.

Syniehubov explains that a new substation will have to be built because the one that was destroyed is beyond repair.

This will take much longer than a couple of weeks or even months, even if the Russians attacks were to stop. "So we could have a rather apocalyptic scenario in which there is a complete blackout?" we ask Syniehubov. "No electricity, no running water, no food...

If there is a power outage, sewage treatment plants won't operate, there'll be no mobile phone service... It's not that hard to understand where we're headed," is how Syniehubov describes the potential future scenario in Kharkiv. The city has already had several opportunities to "rehearse" the apocalyptic scenario, though only briefly, no longer than half a day at a time.

That's how long it usually takes municipal service workers to restore the power supply. When we get back from Balakliia, our hotel manager vividly describes a near-identical collapse scenario that the city has lived through just that day. "There's no power, so there's no running water or heat either, we can't clean [the rooms] or even make a cup of tea.

Staff from other neighbourhoods [of Kharkiv] can't get here because the metro and the trolleybuses aren't running. One of our guests had a train to catch, but he spent the entire morning trying to get hold of a taxi: there's no service and all of the taxi companies' dispatch services also had no power. So he had to run through the empty streets in an attempt to get a lift with someone," the hotel manager explains, making expansive gestures.

Add to this the fact that none of the shops, banks, ATMs, petrol stations, traffic lights - and possibly not even the railways - were working, and the city seems like a set for the sequel to The Day After Tomorrow. Kharkiv, the largest city in eastern Ukraine, is home to electricity and mobile service distribution hubs not only for the city itself, but also for several neighbouring oblasts. The scale of the potential catastrophe would thus not be limited to the city of Kharkiv, but might also reverberate through Sumy, Poltava and parts of Dnipropetrovsk oblasts.

An "open sky" above Kharkiv

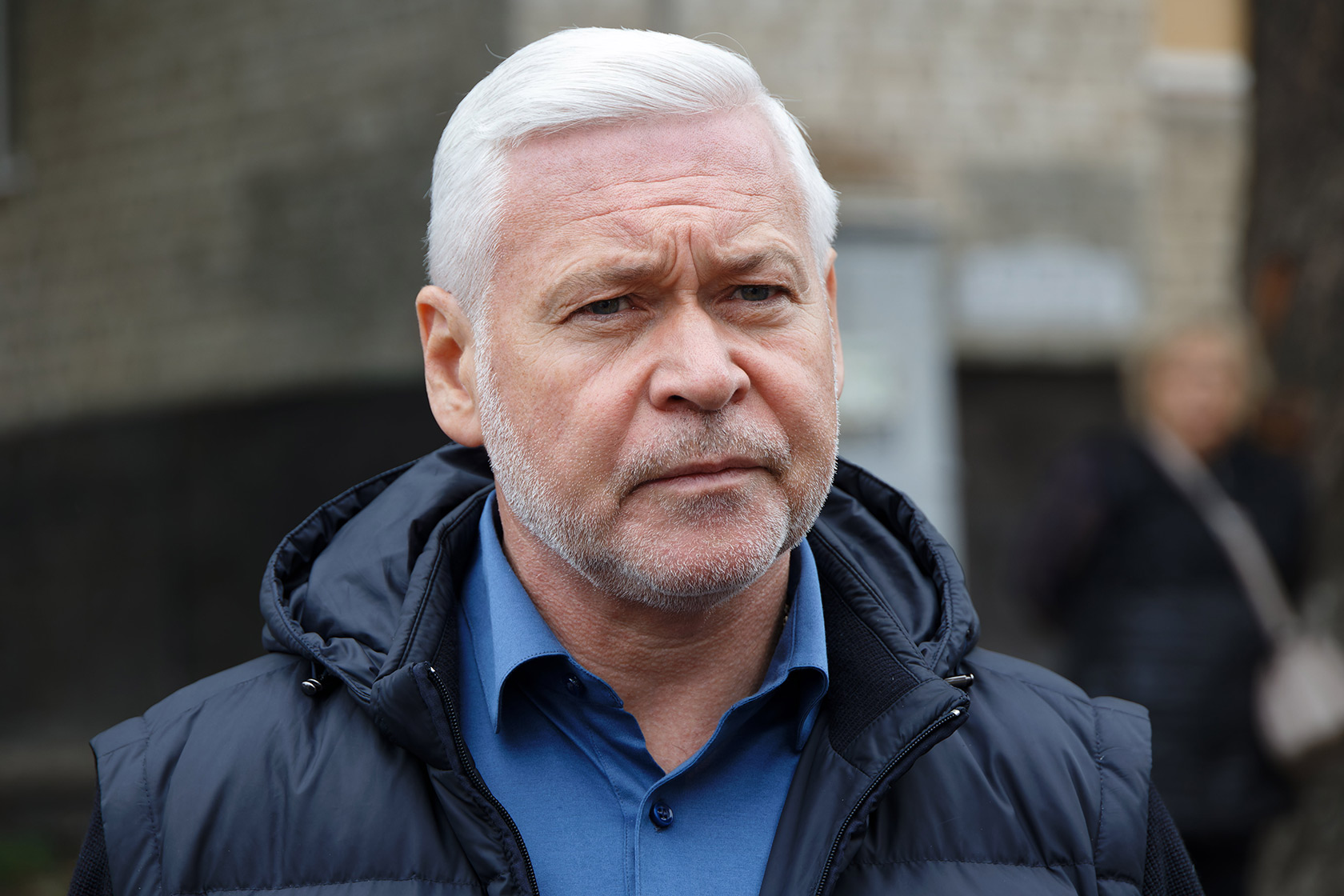

Ihor Terekhov, the Mayor of Kharkiv, gets out of his armoured minivan and immediately begins to order people around.

"Who parked this here? It's hideous. Get it away from here," he says quietly but with great authority to a foreman who couldn't think of anything better than parking an old, tired-looking Gazel van over a manhole gaping open in the road.

Terekhov has just got back from visiting one of the buildings that have been devastated by the Russians and which is now being repaired.

This was the building that Kharkiv city officials would decide to take President Zelenskyy to when he made a brief stop in Kharkiv on his way to Izium. Terekhov estimated Zelenskyy's route, walked through the construction site in his unassuming Prada sneakers, indicated which bit had to be swept, where a small clearing should be created, and where the building's residents should stand. Eventually, Terekhov turns to the Ukrainska Pravda journalists and says coldly, though politely, "So, shall we talk?"

One of the first things we ask is how life in Kharkiv will change following the successful counteroffensive undertaken by the Ukrainian Armed Forces. "It depends on how far back the Russian forces are pushed. But it's really important for the people, they've gained some confidence, a sense of hope.

People here have been feeling pretty tense, to be honest. Many were wondering whether to come back. Now we'll have a bit more certainty and perhaps people will feel more uplifted," the mayor replies, though he immediately adds a less optimistic caveat:

"The only issue is that these non-humans - you can't call them anything else - use MLRSs with a range that allows them to shoot from the territory of the Russian Federation. And even today they shoot from there and destroy our infrastructure. You see what they actually do - they hit transformer substations.

The electricity goes off and people's lives actually stop."

Terekhov says that the only option to avert a catastrophe is to close the sky and build defences that ensure the city cannot be fired on from Russian territory. "And when did you realise you would hold out after all, that there was a chance of holding the city?" we ask the mayor, before the presidential motorcade comes into view. "From day one.

If we hadn't had such confidence, people would have behaved differently," Terekhov answers without hesitation. According to our information, however, he was holding something back. According to Ukrainska Pravda sources within both the Kyiv and Kharkiv authorities, on the morning of 24 February, a few hours after the start of the Russian invasion, neither Terekhov nor Syniehubov, the head of the Kharkiv Oblast Military Administration, could be found.

At the first teleconference with local leaders organised by the President's Office on the morning of 24 February, which Ukrainska Pravda has written about here, there were no representatives from either Kherson or Kharkiv. "The Security Service of Ukraine (SSU) reported that Terekhov and Syniehubov were discussing what to do in the centre of Kharkiv at the apartment of a member of parliament. Meanwhile, panic and rebellion were already brewing in the State Administration and at City Hall," a source within Zelenskyy's team told Ukrainska Pravda.

It all ended up with [Kharkiv's] mayor and head of military administration being immediately detained by the SSU when they arrived at the State Administration. However, the service let them go almost immediately. To the credit of both officials, they found the strength to get their acts together and take control of the situation.

Interestingly, the head of the regional SSU who organised the detention of the Kharkiv leaders at the time was recently notified that he is under suspicion of treason. Now the Office of the President is convinced that Syniehubov has become a favourite at Bankova [the street in Kyiv where the President's Office is located] - at the very least, he is definitely up there in the top three heads of state administrations. And this despite the fact that the Kharkiv Oblast State Administration is currently understaffed, to put it mildly.

"There were days when we had 20 people doing everything. And they managed. We still can't understand why there are a few hundred workers left," Oleksandr Skakun, Syniehubov's deputy, joked in a conversation with Ukrainska Pravda.

Interestingly, it wasn't just minor officials who ran away. Kharkiv is one of the cities that produced the largest number of billionaires and oligarchs. We wondered whether the following people are helping the city...

"Yaroslavskyi promised a billion dollars from the sale of his yacht. And there are many other famous people from Kharkiv. People like Oleksandr Yaroslavskyi [a Ukrainian businessman, formerly co-owner of UkrSibbank and president of Metalist Kharkiv football club], Pavlo Fuks [founder of a development company], Vadym Rabinovych [businessman and co-chairman of the pro-Russian Opposition Platform - For Life party, whose activities were initially suspended by the National Security and Defence Council and then banned by the Ukrainian Court] and so on: are they helping the city now?" we asked.

"We do almost everything ourselves. As for the people you mentioned, since the beginning of the war, I've spoken to Fuks twice on the phone, and once, I think, to Yaroslavskyi. [I haven't communicated with] Rabinovych at all. There was no systemic support for the city.

It's one thing to declare you're going to do something, and another to actually help. We haven't seen any money," the mayor answers with an ironic smile. The presidential guard begins to push journalists and bystanders away from the area where Zelenskyy is about to arrive.

"You know, the main thing now is to close the sky. Because everything could be very difficult. I'm going to say the same thing to the president now," Terekhov says, and he walks away to a group of people including Syniehubov and Kyrylo Tymoshenko, the deputy head of the Office of the President, who came with the group.

"Volodymyr Oleksandrovych, is it possible to close the sky over Kharkiv so that the Russians don't hit critical infrastructure?" we ask the president as soon as we can get a question in.

"It is only possible to strengthen air defence by acquiring new complexes. And this is not a question of money, although it is a lot of money: between half a billion and two billion dollars. But we can find the money.

The question is the countries that manufacture them. There is the US, Israel, there's a joint German-French-Italian company, they produce very good medium-range complexes. The complexes that we need to obtain now are complexes with a small radius of action.

This is the NASAMS [National Advanced Surface-to-Air Missile Systems] that we agreed on with the United States, and Scholz and I agreed on IRIS. They would be of great help to us now; we are waiting for them," answers the president, surrounded by a dense ring of armed guards.

"But you know how it is: our partners want to help us, but they can't give away their ready-made complexes, they can only make new ones. So we are waiting.

The Israelis could help us. But it's more difficult with them," adds the president, slightly shrugging his shoulders. * * *

"How was it possible to hold Kharkiv?" says Roman Semenukha, deputy head of the Kharkiv Oblast State Administration, over a cocktail. "On the one hand, the heroism of the 92nd Brigade, which formed a solid line and prevented the Russians' main forces from entering the city. On the other hand, in Kharkiv, literally in the first few days, the territorial defence forces were packed, everyone was given weapons and they simply killed everyone who broke into the city. Independent Ukraine raised 15,000-20,000 men who together sent the 'Russian world' packing and did not surrender the city."

We met by chance in the Liudy bar, when the city centre finally got electricity in the evening. All the tables behind the wall from us were taken by the Kyiv delegation of the Ministry of Infrastructure, headed by Oleksandr Kubrakov, the [infrastructure] minister. To the left of the bar, a group of foreign journalists are looking at their phones and singing along as best they can to the song "Stefania" by Kalush [the Ukrainian band that won Eurovision in 2022].

A little further on, fighters from Khartiia [a volunteer battalion from Kharkiv] are discussing their possible redeployment to a recently liberated city in Kharkiv Oblast. There are many people in the Liudy bar whose humanity and sincerity have been brought out by the war. We're surrounded by light, conversations and jokes.

But once you pay the bill and take five or six steps out of the bar, the contrast and surprise will take your breath away for a moment. There is not a single car, not a single passer-by, and not a single light in the centre of a million-strong metropolis at half past eight in the evening. Only a dead, all-absorbing silence and darkness, which envelops everything around, fills the streets and yards, seeps into the smallest cracks.

It's here, in this dark silence, that you're hit by the true realisation of the tragedy that this great Hero City is going through. And the only thing that saves us from despair is that somewhere in this darkness, in cramped yet friendly basements, People who dream of victory are gathering together. Author: Roman Romaniuk, Ukrainska Pravda

Photographs by Dmytro Larin, Ukrainska Pravda

Translating: Olga Loza, Elina Beketova, Myroslava Zavadska

Editing: Teresa Pearce