“Help me.” Story of deportation of teenager who managed to return to Ukraine

At the end of December, a 16-year-old Serhii was brought back to Ukraine, it was reported by the Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights. Months before in March, the then 15-year-old boy was forcibly taken to the occupied territory and deported to the Russian Federation, where he was placed in a Russian foster family. The Russian ombudsman personally participated in issuing the boy a passport against his wishes.

Thanks to perseverance, Serhii managed to return to Ukraine. The author of this text managed to find Serhii while he was still in Russia and uncover what path the boy took, how he ended up in Russia, and who in the occupied territory participated in the boy's deportation. We can finally publish key elements of the investigation and share the story of Serhii's deportation.

***

Almost nothing was known about Serhii at first, only his name and that he used to live near Mariupol, and that he was placed in a Russian foster family in the suburbs of Moscow. This could be seen in a Russian propaganda video, one of those videos that the Russians began filming on 24 February on deported Ukrainian children; designed to glorify their new Russian "adopters". The video does not explain in any way how the Ukrainian 16-year-old Serhii ended up in Russia.

It was scripted to create the illusion of a "happy proper family" and their "accomplishments". It was this video that helped to locate Serhii back in November. Without any additional mechanisms and resources, solely with the help of the Internet, the entire search process took a maximum of an hour; such a situation of course is pure luck, and unfortunately unique.

Many details of this investigation and story will not be released due to the safety risks involved. "I want to return to Ukraine, please help," was one of the boy's first phrases. This is how the story of his deportation, transfer to a Russian family, life in the Russian Federation and return to Ukraine became known.

*All the events described here are based on the testimony given by him and his relatives in Ukraine. We can't mention their names because of the security risk for them and Serhii.

Photo of Serhii coming backPhoto: Office of the Ombudsman of Ukraine

Photo of Serhii coming backPhoto: Office of the Ombudsman of Ukraine

Who are you, Serhii?

In April 2022, Serhii turned 16 years old. Serhii's family lived near Mariupol.

The boy's parents had both died. In 2021, at the age of 15 he remained an orphan. Besides him, there were several other children in the family.

Serhii was the youngest. One of Serhii's older sisters applied for custody of the boy in the summer of 2021, when Serhii was 15 years old and about to enter college to become a mechanic. But the child welfare authorities of the local administration, for some reason, denied the sister permanent guardianship over her brother, citing that the college director could provide guardianship.

In addition to Serhii, the director had more than ten such children under his supervision; those without parental care or with disabilities.

The beginning of the invasion. The way home

On 24 February, when the full-scale invasion was launched, Serhii recounts that the director of the college first took the children under his care to Zaporizhzhia, a territory then controlled by Ukraine, and he soon disappeared. "One of these guys who was evacuated wrote to me that he is safe, but we didn't know anything about the director," said Serhii.

But Serhii was not evacuated together with these children. The guy decided to go home with another college student, and for some reason, no one stopped him. They decided to walk almost 50 kilometers together to their native home, in winter, through the already occupied territory.

He saw Russian military equipment driving and heard shells exploding. "We were just walking. We didn't care, we just wanted to get home," he says.

Hiding to rest, and without the possibility of somewhere to warm up or stop, the boys understood that their decision had probably been too risky. However, it was too late to return. "I would have left there and returned back to the territory controlled by Ukraine if I could," Serhii recalls now.

The boy was able to stay at home for no more than two weeks. Then during the last week of March the Russians forcibly began removing people from Mariupol to the outskirts under the guise of evacuation; from there people were immediately booked "for departure" by buses, one way tickets only - to Russia. People were not given any choice on where to go.

This also took place in the settlement where Serhii was at that time. He later learned that all his relatives had also been deported.

Abduction and deportation

Two weeks after Serhii returned, a district police officer arrived at his house. He was well known to all the local residents, as he was a police officer until 24 February.

He told Serhii's relatives that he had to take him to the hospital for a medical examination. He referred to the order of the guardianship service of the local administration since Serhii did not have a guardian. His relatives said that Serhii was not at home.

On the way from their house, the police officer spotted Serhii on the street and called him. Serhii knew him well. "He called out my name, asking me to approach him, and then said that since I do not have a guardian, I must be taken to the hospital temporarily, to determine who will take care of me.

I reminded him, I have a guardian, who is the director of the college. But the police officer said: "There is no director. You're going with me to the hospital, I have an order from the guardianship service (juvenile affairs service of the local administration - author)," Serhii recalls.

You might be wondering why they went to the hospital? There were simply no other special care facilities in that area, so hospitals and similar facilities were used by the occupiers as temporary detention centers for people like Serhii. Similar centers already functioned throughout the occupied territory as part of an established scheme for the deportation of Ukrainian children by the Russians.

Why did Serhii go with the district police officer? He realized that his village was already occupied. However, when the district police officer arrived, he did not identify him as a threat.

"He never treated me badly before. I thought that he's better than the Russians," describes Serhii. Of course, Serhii understood that the district police officer hadn't worked for the Ukrainian authorities at that time.

On the other hand, how could Serhii refuse? Unlikely. He did not know then that children were being collected all over the occupied territory.

Serhii was kept in the hospital for several days. Once, people from the local guardianship service visited Serhii. "They said there was a family nearby, and if I wanted, there would be an opportunity to see my family.

And then it turned out that they sent me to Donetsk," says Serhii. His relatives found out about this afterwards accidentally from an employee of the "guardianship service" who helped the occupation authorities deport children. She had previously worked in the service prior to the occupation.

On arriving in Donetsk, Serhii was again placed 'allegedly temporarily' in yet another hospital, where other children displaced from territories occupied by Russia were "overexposed". "All orphanages and other institutions for children lacking parental care had already been filled with children brought from other occupied territories," says Serhii. There he "temporarily" spent almost two months.

His sole Ukrainian document, his birth certificate, was "lost". "I asked them where it was. They told me they sent it to Moscow and that it was lost there.

Further, I didn't have a Ukrainian passport because when I turned 16, I was already in their hospital," added Serhii. In Donetsk, Serhii was informed that it was dangerous to stay there due to shelling, and therefore he would be taken to an orphanage in Russia. Serhii was taken from Donetsk to Rostov-on-Don, from where he was taken by plane to an orphanage in the suburbs of Moscow.

He spent a month there, and from there he was transferred to another orphanage, in Yegoryevsk. "We'll get you back later, they said," recalls Serhii. Perhaps the reason why he was kept in the occupied territory for 2 months was related to processes that took place in Russia.

When the deportations began, and Russian ombudsman Maria Lvova-Belova started promoting the adoption of deported Ukrainian children, Russians faced the reality that adopting such children is illegal, even in Russia. Maria Lvova-Belova lobbied for changes to Russian legislation that would legalize the procedure for adopting children of another nationality. Her idea stirred up a lot of controversies, even in the Russian political environment.

The fact is that according to one social study conducted in Russia (2021), less than 50% of Russian citizens bare a Slavic appearance due to assimilation with other nationalities. Russian propagandists consider this a problem (from the conclusions of the report by the Eastern human rights group and the Institute for Strategic Studies and Security). Solving their demographic "problem" at the expense of deported Ukrainians sounds like a terrible nightmare of 1939-45, but this is a reality.

And just as Serhii and other Ukrainian children ended up in an orphanage in the Russian Federation, the president of the Russian Federation personally signed a law that removes obstacles to the adoption of Ukrainian children. And the adoption process began in conjunction with propaganda videos that glorified "hero parents", who are in reality participants in a horrific crime. So, after a month's stay in an orphanage in Russia [during the summer of 2022], Serhii arrived at the home of a married Russian couple, the "new family".

By the time we first communicated, Serhii had been in this family for 4 months. It turned out that before that he was trying to find help on his own to return to Ukraine. "I thought about earning some extra money, but I didn't have the opportunity... and where can I go without a passport?

The police would stop me," he said.

Serhii was met at the train stationPHOTO: Office of the Ombudsman of Ukraine

Serhii was met at the train stationPHOTO: Office of the Ombudsman of Ukraine

Ukraine in touch

There was limited time for communication, because Serhii's "parents" monitored and controlled his movements: a geolocation app was forcibly installed on his gadget, and he could only talk during specific times. Serhii's voice sounded confident: "I want to return to Ukraine. Will you help me?

Please."

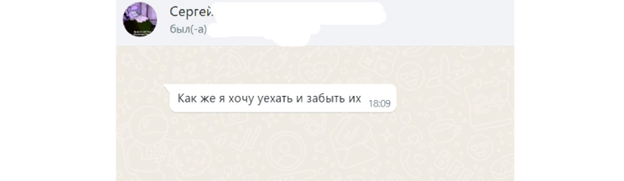

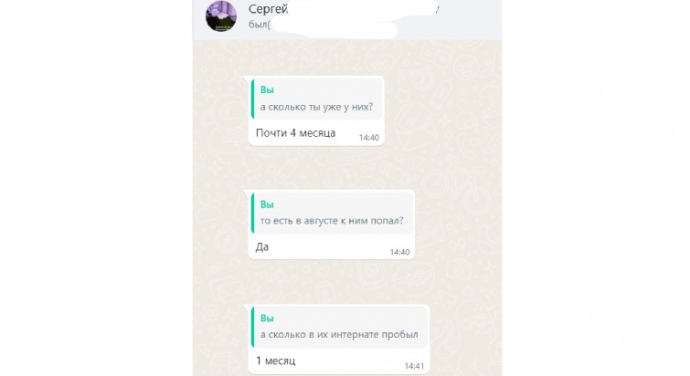

Excerpts of texting between Serhii and the journalist

Excerpts of texting between Serhii and the journalist

There was hope in the boy's voice every time. And he was still there, waking up every morning in a foreign country that was bombing his native country, among strangers who were hostile to the language of his country, and who decided everything for him and for some reason believed that Serhii should be happy about it. "I immediately told them that I would leave them.

They say, "Oh, why, what don't you like," he remembers. This family already had three children of their own and one adopted child. Therefore, Serhii became the fifth.

The family was religious, often went to church, and controlled the time he could use the phone. "What was most annoying was that they discussed Ukraine all the time. I didn't like that at all.

I asked them not to do it, but they didn't care, they would just sit down and wouldn't stop. Constantly, when I was at home, they started: "Nazis in Ukraine", and that's it. I just kept quiet, didn't talk to them," says Serhii.

Excerpts of correspondence between Serhii and the journalist

Excerpts of correspondence between Serhii and the journalist

The final video about him and his new "family" Serhii was not shown.

He was forced to communicate with journalists: "I wouldn't watch it. I don't want to. I hate them."

A separate point in this story is that he was forcibly issued a Russian passport, when he became a member of a Russian "family". "This was done by Maria Lvova-Belova, it was her initiative," said Serhii. But these "parents" immediately confiscated his passport, allegedly "for adoption purposes", but Serhii thinks in fact, it was done to prevent him from going anywhere.

After all, according to Russian law, from the age of 16 upwards, children with a Russian passport can travel freely around the country. All this time, Serhii patiently waited for help, that there were still people in Ukraine who needed him, that they were waiting for him here and would not leave him. That this help will really come.

He never gave up. "I wrote to people to take me away," says Serhii. We counted the days together.

Ukraine was waiting for him. And Ukraine had waited.

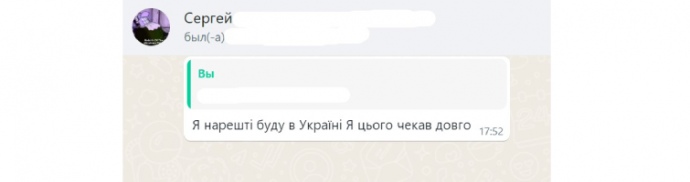

Excerpts of correspondence between Serhii and the journalist

Excerpts of correspondence between Serhii and the journalist

Comeback

We can say that Serhii initiated his departure himself, by writing in the right place. He is well-versed in the internet world.

Every day was equally difficult while he was there. And then there were a few days of silence. And at some point, a sudden message came.

It contained a short text: "I just entered Ukraine. Happy St. Nicholas Day to you?"

It was undoubtedly the best gift for all of us. The journey was incredibly difficult. And on 20 December, the Office of the Ukrainian Ombudsman Dmytro Lubinets, officially announced that Serhii had been returned to Ukraine.

Serhii's meeting was confidential. The report added that Serhii was met on the border with Ukraine. In the published photos, Serhii holds the Ukrainian flag.

For ethical and security reasons, his face is hidden. "When I was far away, the "family" wrote to me - they said, come back, we will give you money (for travel), come back, otherwise we will have problems. That is, probably, the main thing is that they will have problems," Serhii recalled.

Perhaps these people will really have "problems". But the foster family took a child deported from Ukraine to their home. And no matter what propaganda pours into the ears of Russians, such "parents" are accomplices in a crime.

And not just a crime, but a genocide, as stated in Article 6 of the Rome Statute - "genocide", one of the points of which is "the forced transfer of children of one group to another group". This crime falls under the direct jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court and will be investigated within the framework of the main case. The identities of those who participated in the crime will be established without fail.

And no matter how good in their understanding those Russians who take Ukrainian deported children into their families are, all of them will be tried sooner or later. It is known that in Ukraine Serhii has relatives who will take care of him. Serhii already has plans in Ukraine.

He plans to continue his training, most likely as a mechanic - this is his dream. Also, he has already received a Ukrainian passport. I was really looking forward to it.

All the bad things are over for him. But not for thousands of other Ukrainian children deported to Russia. Not all of these children are as old as Serhii.

Not everyone has the opportunity to ask for help. "Russian children's Ombudsman Maria Lvova-Belova, who visited children "for sweet communication" on camera for propaganda media, decided the fate of Serhii and other deported Ukrainian children-adoption into Russian families," said Dmytro Lubinets. Earlier, during a special report, Dmytro Lubinets, the Ombudsman, noted that his Russian "colleague" does not hide this crime:

"On the official website, the representative of the Russian President, Maria Lvova-Belova, officially admits that she personally deports Ukrainian children, takes part in this, and that Ukrainian children, according to her, are "very bad-minded". That is, they sing Ukrainian songs and say "Glory to Ukraine". And she adds, "It's okay, we'll re-educate them." We draw the attention of all international experts to this.

And we demand that separate proceedings on the forced deportation of children be opened at the level of an international tribunal." *** According to the research conclusions of the Eastern human rights group and the Institute for Strategic Studies and security, which investigated the deportation of children, it was a planned operation with a pre-prepared system, with routes, a network of so-called "detention centers" in the occupied territories, and a step-by-step deportation scheme.

Human rights activists found out that Russians deport not only orphaned children, but also look for any opportunity to deprive parents of the right to separate them from their child and deport these children. In their investigation, they conclude that forced passport registration, an exam on ideologically correct upbringing for new parents of Russians, a change of first and last names, and deportation are direct signs of genocide of Ukrainians. ***

According to the National Information Bureau of Ukraine, for the period from 24 February to 1 November, 2022, the number of deportees (forcibly removed from the territory of Ukraine to the territory of the Russian Federation or the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, and Sevastopol) is 45,995 people, including 37,855 adults and 8,140 children. But this is only the data that Ukraine managed to verify. And this only means that the number will grow.

The Russians themselves announce the figure of about 700,000 Ukrainian children, whom they took out. The article was created with the support of The Reckoning Project - an international project to document testimonies that will have legal force in war crimes cases. We have also published a translation of the article and the documentary film "Dad, You Have to Come Or We Will We Adopted." The terrible war saga of one Ukrainian family" about the abduction of children from Mariupol.

It was also created by The Reckoning Project team. Mariia Lebedieva Translators: Elina Beketova, Yelyzaveta Khodatska, Ilona Pylat

Editor: David Matthews