Building a new life: how people who fled to Zaporizhzhia from Russian-occupied Melitopol, Berdiansk and Tokmak stay connected to the cities they left behind

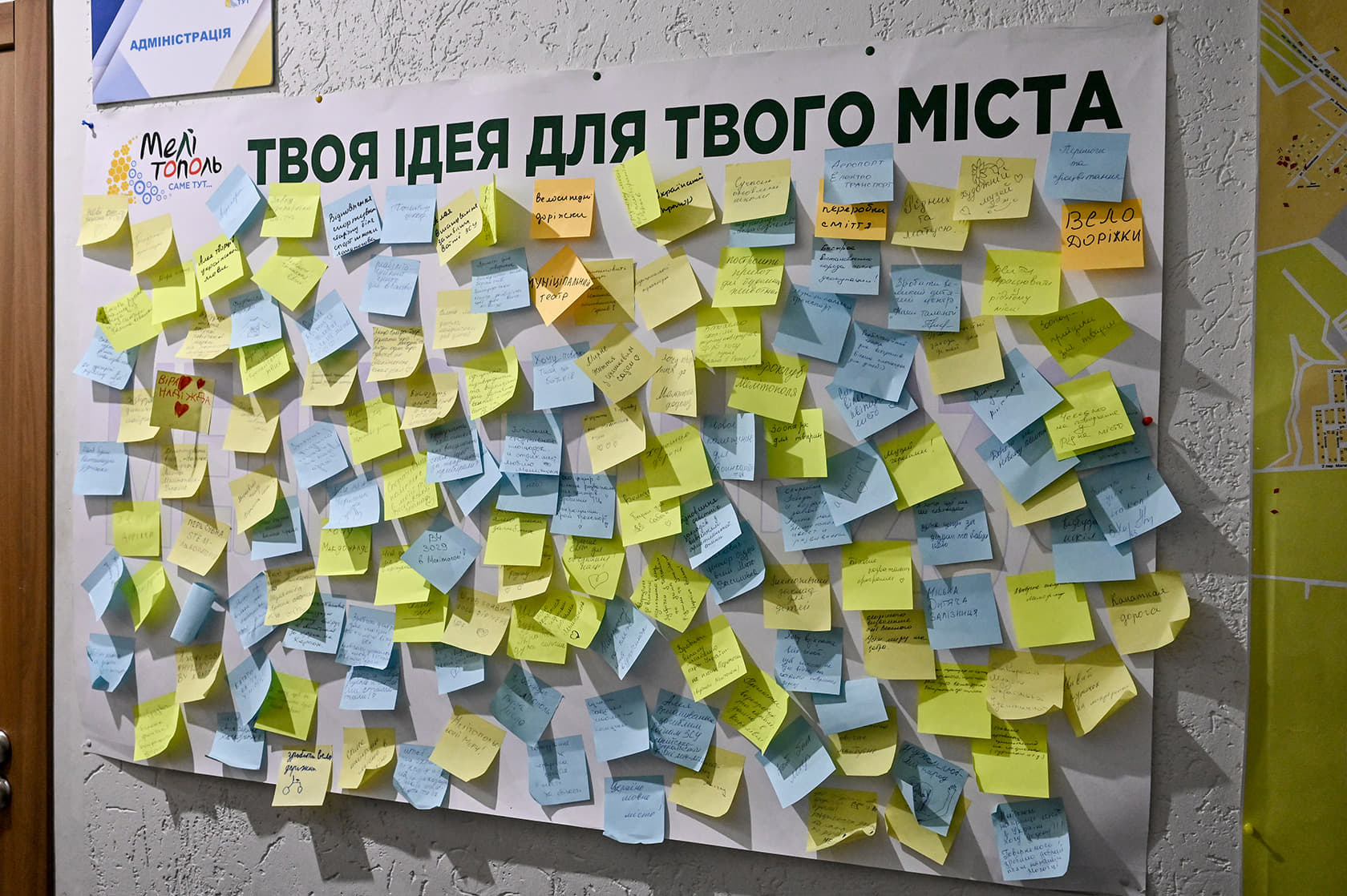

I'm looking at a large notice board headed "Your ideas for your city". It's covered with hundreds of blue and yellow slips of paper - all handwritten notes from people who have fled the Russian-occupied Melitopol district in Zaporizhzhia Oblast, detailing their hopes for their native region after it is liberated from Russian forces. "Build cycle paths", "Create a memorial avenue for the fallen soldiers from the Ukrainian Armed Forces", "Invest in a municipal theatre", "Build a recycling plant", "I want a McDonald's", "A cherry festival", and hundreds of other dreams.

Some of the notes read more like a cri de coeur than a plan for action: "I want the Russians to leave the city as soon as possible", signed "Halyna Ivanivna". Or: "I want all those bastards deported from my native city." You can find this notice board of ideas in the city of Zaporizhzhia, at Right Here - a space where people from Melitopol and its environs, which have been occupied by Russian forces since early on in the full-scale war, can get various types of aid and assistance.

Right Here has been open for two years.

Advertisement: ????? "???? ???? ??? ????? ?????"

????? "???? ???? ??? ????? ?????"

Alina, 25, has received legal advice and mental health support here on several occasions. Today she is here with her four-year-old daughter to collect humanitarian aid. Before the full-scale Russian invasion, she lived in a village in the Melitopol district, and fled to Zaporizhzhia in 2022.

Alina is a trained pharmacist, but she can't get a job at a pharmacy because she has no one to look after her daughter while she's at work. Kindergartens and schools in frontline areas don't offer in-person teaching, so Alina gets by working remotely as a translator and editor.

Alina's four-year-old daughter is terrified of explosions and thunder

Alina's four-year-old daughter is terrified of explosions and thunder

Alina has been thinking about finding a child psychologist because of her daughter's fear of loud noises. "When she hears thunder, she screams and drags me into the hallway - let alone explosions," Alina says as she waits for her turn. It's hot and sunny outside, but no sunlight reaches inside the building.

The windows have been boarded up since Right Here's premises were damaged in a Russian attack on Zaporizhzhia on 6 April.

Advertisement:Despite her work and childcare troubles, Alina is more at ease in Zaporizhzhia than anywhere else, in large part because she's still close to her native village, which - for now - remains under Russian occupation. Also because she has some friends here: many other people who fled the Melitopol district have settled in Zaporizhzhia. "It's scary going somewhere where you don't know anyone," Alina says.

She explains that some people move to Zaporizhzhia because their partners or relatives are serving in the armed forces. Something specific to Zaporizhzhia is the fact that the majority of internally displaced people (IDPs) here come from other districts of Zaporizhzhia Oblast, the ones that have been occupied by Russian forces. As of late May, according to official data, there were 226,300 IDPs in Zaporizhzhia Oblast - the equivalent of the population of a mid-sized Ukrainian city like Ternopil.

Alina, 25, from a village in the Melitopol district, stands by the memorial wall honouring fallen soldiers from the Armed Forces of Ukraine at the Right Here centre in Zaporizhzhia

Alina, 25, from a village in the Melitopol district, stands by the memorial wall honouring fallen soldiers from the Armed Forces of Ukraine at the Right Here centre in Zaporizhzhia

The needs of the people who fled to this large industrial city have changed over the course of the past two years.

Back in 2022, people fleeing Russian occupation needed food, clothes, personal hygiene products, medicines, and a temporary place to stay. Now, their most pressing issues are housing, jobs, and their children's education, since schools in Zaporizhzhia still operate online, says Oleksandr Svystun, acting director of the Association of Unconquered Hromadas. [A hromada, or community, is an administrative unit designating a town, village or several villages and their adjacent territories - ed.] The newcomers have gradually got used to living in Zaporizhzhia, and some even consider themselves fully assimilated.

Many of them continue to keep in touch with the towns and villages they came from even after two years in their new city. "If we lose that connection, who will go back after those areas are liberated?" says the head of the Right Here humanitarian centre. She asks us not to disclose her name, because she has relatives who are still living under Russian occupation.

Advertisement:Lenin didn't dance

Artem Shuliatiev, principal of the Melitopol Children's Arts School, proudly shows us the premises his school will now occupy in a new youth centre in Zaporizhzhia. There are drums and guitars everywhere, brightly coloured drawings on the walls, and colourful beanbags in the lobby.

Artem Shuliatiev, principal of the Melitopol Children's Arts School, at the premises his school will now occupy in Zaporizhzhia

Artem Shuliatiev, principal of the Melitopol Children's Arts School, at the premises his school will now occupy in Zaporizhzhia

In April 2022 Shuliatiev went through a similar experience to many internally displaced people in Ukraine: fleeing the occupation, work and housing issues, and the difficult process of reinventing himself in a new city.

After Russian forces entered Melitopol on 26 February 2022, the Melitopol Children's Arts School was closed and didn't reopen for the whole of March. Several of the school's staffers tricked Shuliatiev into coming to the school: they said they needed to pick up some things they'd left behind and asked him, as the principal, to let them into the building. When Shuliatiev arrived, instead of his colleagues he was greeted by four Russian soldiers, who took him to his office "for a chat".

One of them asked Shuliatiev if the school had copies of Lenin's works. "Lenin didn't sing or dance, so we don't keep his works in our arts school," he replied. The Russians wanted him to resume lessons at the school. Two other headteachers of Melitopol schools who had refused to collaborate with the Russians were abducted around this time.

Shuliatiev knew that he had to get out of the school at all costs. Promising to talk to his colleagues, he went home, grabbed his family - wife, daughter and son - and fled Melitopol. The family has lived in five different rented apartments during their two years in Zaporizhzhia, even though they owned three in Melitopol.

Shuliatiev says housing is a huge issue for IDPs in Zaporizhzhia. Last year, Shuliatiev taught a kids' guitar class at the Right Here centre in Zaporizhzhia, and got involved with the centre's other work as well. In 2024, the Melitopol Children's Arts School has opened its doors again, this time in Zaporizhzhia, thanks to grants from international partners.

Now 130 children will be able to study singing, piano, guitar, violin, drums, art and drama here - entirely free of charge.

The Melitopol Youth Centre in the city of Zaporizhzhia

The Melitopol Youth Centre in the city of Zaporizhzhia

Over time, several departments of Melitopol's city administration have moved into various buildings, Right Here says. The sports department has rented a gym and started sports clubs. The education hub plans to open a mixed-format school that will combine offline and online learning.

And the medical department will be operating in a hospital starting July. Right Here has launched a new service - assistants for veterans - and organised summer holidays in Ukraine and abroad for schoolchildren. There is, however, a sizable group of IDPs who are only interested in humanitarian aid, rations and nothing else, the organisation admits.

Right Here has recently launched a new service - assistants for veterans

Right Here has recently launched a new service - assistants for veterans

After last year's much-anticipated Ukrainian counteroffensive, on which the former Melitopol residents had pinned high hopes, many people fell into depression after losing the hope of returning home soon, Shuliatiev says.

Their plans, like the future itself, are uncertain. Things became even harder after the state cut payments for IDPs. Some of them even went back to the temporarily occupied territories.

Adapting to the constant changes is hardest of all for the children. Shuliatiev reveals that since his family's latest move to another rented apartment, his 12-year-old daughter is reluctant to make more new friends only to lose them later.

Advertisement:Internally displaced doctors

Melitopol isn't the only city in Zaporizhzhia Oblast whose institutions have relocated to the city of Zaporizhzhia. A multidisciplinary intensive care hospital from the Russian-occupied city of Tokmak opened here in November 2023.

It's headed by Yevheniia Tupozliieva, who lived and worked in the now-occupied city of Berdiansk before the full-scale invasion.

Yevheniia Tupozliieva, a medic from Berdiansk, is now the director of the Tokmak Multidisciplinary Intensive Care Hospital

Yevheniia Tupozliieva, a medic from Berdiansk, is now the director of the Tokmak Multidisciplinary Intensive Care Hospital

This two-storey medical institution is staffed by IDPs from the occupied cities of Tokmak and Berdiansk, as well as from Zaporizhzhia itself and Ukrainian-controlled Orikhiv, which suffered extensive damage during the hostilities. The institution has been built from scratch. First, administrative and junior medical staff were hired.

There was nothing in the clinic to start with. Tupozliieva recalls how the staff cleaned and cleared away rubbish together before preparing for the opening. Gradually more staff joined the team - a general practitioner, family doctors, a neurologist, an endocrinologist, a paediatrician, and finally a gynaecologist.

Now there are 13 doctors on staff. There's also a lab where medical tests can be done. Initially, the problem was that very few people in Zaporizhzhia knew about the hospital.

Oksana Petrovska moved to Zaporizhzhia from Orikhiv and is in charge of the lab at the relocated Tokmak hospital

Oksana Petrovska moved to Zaporizhzhia from Orikhiv and is in charge of the lab at the relocated Tokmak hospital

"Our girls hand out flyers in the street during their lunch break [to promote the hospital - ed.]," Petrovska says.

People also learn about the hospital when they come to collect humanitarian aid, which is distributed outside the clinic by the Tokmak Military Administration. Here, IDPs find out that doctors from their hometowns of Tokmak, Berdiansk and Orikhiv are here now. Gynaecologist Natalia Anisimova, who joined the medical staff in April 2024, headed up the women's health centre at the Tokmak hospital for 20 years.

She recalls the first few weeks of working under the Russian occupation with horror. "A woman came to an appointment. I asked her: 'Are you sexually active?' She answered: 'My husband was run over by a tank just outside the city administration'," Anisimova reveals.

She left Tokmak on 13 April 2022 because she could not endure the occupation psychologically. "I couldn't live like that. Why did I have to have a Russian passport? Why did I have to pay taxes to their budget?

Then they use that money to launch attacks on us," Anisimova explains.

Gynaecologist Natalia Anisimova headed the women's health centre at the Tokmak hospital for 20 years and now works at the relocated hospital in Zaporizhzhia

Gynaecologist Natalia Anisimova headed the women's health centre at the Tokmak hospital for 20 years and now works at the relocated hospital in Zaporizhzhia

After moving to Zaporizhzhia, Anisimova's first priority was to find a job for her daughter, a nurse, rather than for herself. The hardest thing was being left behind, she explains - suddenly realising you're not needed anymore after you've dedicated your whole life to your job. So when the Tokmak hospital where she used to work offered her a part-time position, she decided to start a new professional life.

Patients started arriving, both IDPs and Zaporizhzhia residents. "The day before yesterday four women came!" Anisimova says happily.

Advertisement:All the services provided by this medical institution are free, including medical tests, which is an important aspect for the IDPs, clinic staff say. The lab can run 350 tests per day, but so far the average is 25 per day, says Oksana Petrovska, who worked in a lab in Orikhiv for 26 years.

People waiting to be seen in the relocated hospital in Zaporizhzhia

People waiting to be seen in the relocated hospital in Zaporizhzhia

Like the other doctors from the Tokmak Multidisciplinary Intensive Care Hospital, Anisimova enthusiastically lists the services their medical institution can now provide in Zaporizhzhia. But when the doctors think back to their past lives before the full-scale invasion or talk about future plans, they, like other IDPs, often can't hold back their tears.

Above all, the medical staff cling to this hospital because it gives them the opportunity to work when "nobody needs you in Zaporizhzhia", Petrovska explains. In any city there are people who refuse to accept the IDPs, and you can't escape that - whereas at the hospital everyone understands each other, both doctors and patients. But another key objective of the hospital is to preserve the human resources potential of Zaporizhzhia Oblast, Tupozliieva explains.

It's important that people return home and work there when the temporarily occupied territories are liberated. "We're building a new life on the ruins of the old one," she says. Svitlana, a matron, is planting and watering flowers outside the hospital, just as she used to do in her hometown of Tokmak. Kristina Berdynskykh

Photo - Dmytro Smolienko Translation: Olya Loza and Polina Kyryllova Editing: Teresa Pearce

This article was written for the Ukrainian School of Political Studies and Ukrainska Pravda with the support of the Partnership Fund for a Resilient Ukraine, which is funded by the governments of the UK, Estonia, Canada, the Netherlands, the US, Finland, Switzerland and Sweden.