Undersea warfare in the Baltic: Why is Russia destroying EU and NATO countries' critical infrastructure?

Unable to sway the countries supporting Ukraine, the Kremlin has resorted to hybrid tactics to disrupt energy links between EU members. If left unchecked, the incidents in the Baltic could occur in other seas as well. The cold waters of the Baltic Sea have turned into a hot theatre of war and hybrid special operations in recent months.

During this time, three key types of undersea communications have been affected: a gas pipeline, communication lines, and a power cable. Investigators suspect deliberate actions by Russia in almost every case. The Kremlin habitually denies everything, saying "You try to prove it".

Advertisement:Why would the Kremlin be behind the sabotage in the Baltic Sea?

Is there a risk of a surge in sabotage incidents, and how can hybrid aggression be countered?

Sabotage in the Baltic Sea

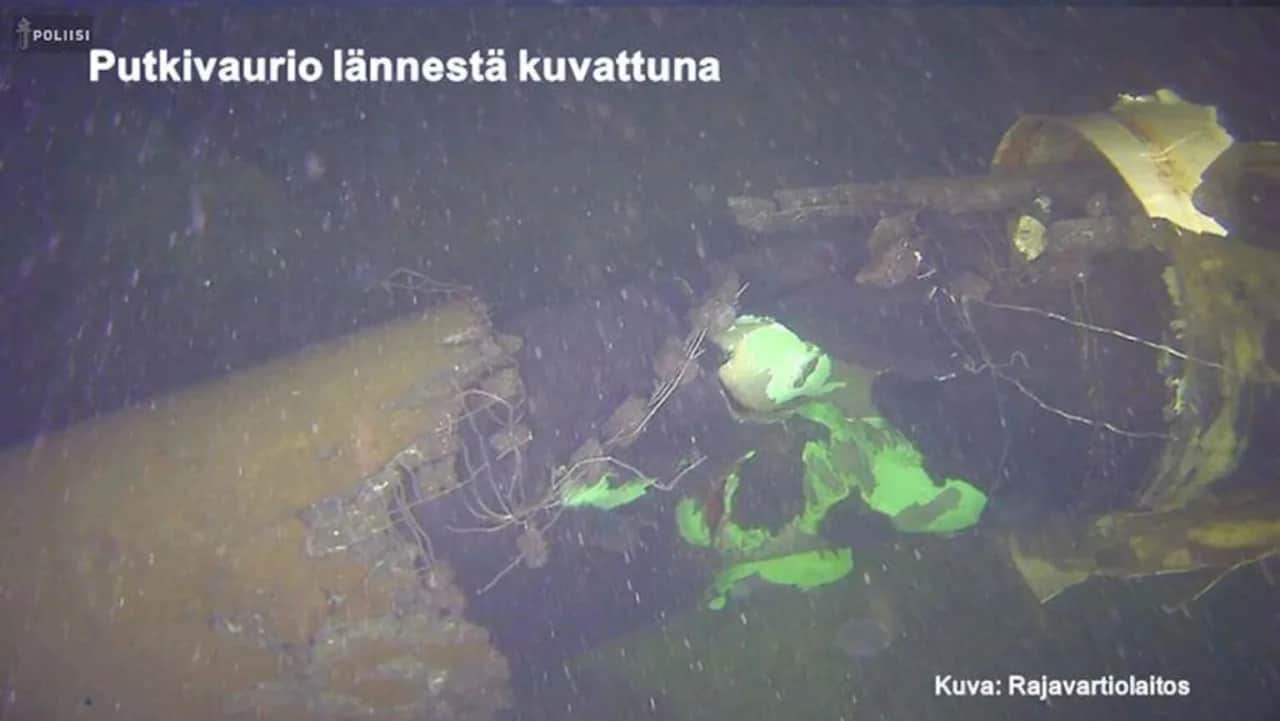

Four particularly egregious incidents involving NATO and EU critical infrastructure have rocked the waters of the Baltic Sea since the onset of Moscow's full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The first occurred in October 2023: the Balticconnector gas pipeline and data cable connecting Estonia and Finland across the Gulf of Finland were severed. Finland's National Bureau of Investigation has said the Hong Kong-flagged vessel Newnew Polar Bear was involved.

It was its anchor, which was later removed from the seabed, that caused the damage. The incident is still under investigation.

The damaged power cable between Estonia and Finland is expected to be repaired by August 2025.

The damaged power cable between Estonia and Finland is expected to be repaired by August 2025.

At the time, the incident was deemed an accident, as it was the first of its kind. However, in November 2024, a similar event occurred.

The Chinese ship Yi Peng 3, which departed from the Russian port of Ust-Luga on 15 November, severed two communication cables - one linking Sweden and Lithuania and the other between Germany and Finland. Swedish police investigators suspect that the captain of the Chinese-owned ship, which dragged its anchor along the seabed for over 160 km, may have been following orders from Russian secret services. Russian nationals were also among the crew. "This raised alarms throughout the region.

We must give credit where it's due: [NATO] warships swiftly seized the vessel. The investigation is ongoing," said Mykhailo Honchar, Presiden of the Kyiv-based think tank, Strategy XXI Centre for Global Studies.

Damage to the Balticconnector gas pipeline linking Finland and Estonia was discovered on 7 October

Damage to the Balticconnector gas pipeline linking Finland and Estonia was discovered on 7 October

Some still labelled this new incident as an accident. However, when a third event of this type took place on 25 December, this time involving the EstLink 2 power cable between Estonia and Finland, it became clear that it was no accident.

Repairing the 650 MW cable will take more than seven months, with completion expected by the end of July at the earliest. However, even that incident was not the last. A submarine communication cable connecting Latvia and Sweden was damaged in late January 2025.

The cable was severed by a Chinese-owned vessel, the Vezhen, which had also departed from the Russian port of Ust-Luga. The owner of the ship confirmed that it was their tanker responsible for the incident, although they maintained it was unintentional. According to the owner, one of the multi-tonne anchors fell to the seabed due to strong winds and struck the fibre optic cable. The vessel was seized and sent to Swedish territorial waters for investigation.

Who stands to benefit from the disruptions?

Many investigative bodies and EU politicians have suggested that Russia may have been involved in these sabotage attacks.

"There's no doubt who was responsible for these incidents", says Honchar. "The investigation will undoubtedly continue and it will be a lengthy process. Some may question whether it was deliberate sabotage or an accident. As is typical of the Russians, their response is: 'You prove it'.

"This has alerted many officials in the EU and NATO, and consultations have been held. The Kremlin's covert actions can be seen as a warning to the countries of the region and to the EU and NATO - these are merely isolated cases of communication disruptions and it may get worse. Imagine if such actions become widespread."

Read also: How Western energy sanctions against Russia are failing

He suggests that this could be a specific type of cooperation between Russia and China. "I allow for the possibility that the Russians may be working with the Chinese 'behind the scenes' as it is not the vessel's owner making a certain move, but the crew. Russians often work on these ships - not just as ordinary sailors but as captains or first mates.

This may be a form of cooperation where each side plays a role." During a press conference, journalists questioned Kremlin leader Vladimir Putin about Moscow's potential involvement in the Baltic sabotage, which he dismissed as "complete nonsense". "It could have been anything...

Some technical [fault] perhaps... Someone may have hit it with some hook, I don't know... earthquakes do happen, although rarely. Maybe some [tectonic] shifts...

I don't know, let them investigate", Putin said, trying to present his vision of the incidents.

Why the Baltic and who is next?

Russia exports the lion's share of its oil and oil products through its ports on the Black and Baltic Seas. When it comes to energy exports, Russia is less concerned about the Black Sea as it has a somewhat unpredictable but generally stable ally there in Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. In the Baltic region, discussions took place in 2024 on restricting Russian oil traffic, which had started to pose a threat to the environment.

In recent years, Moscow has unilaterally loaded its ships crossing the Baltic Sea with a massive volume - up to 100 million tonnes annually - of oil and oil products, which are dangerous cargoes. The consequences of this, compounded by the use of obsolete tankers with no insurance, were highlighted by an incident involving two vessels near the Kerch Strait. "Recently, discussions have begun in the Baltic about the need to limit oil traffic", Honchar points out. "This is especially true since it comes from an aggressor country financing a war with this money.

That's why Russia launched an offensive in the Baltic [Sea] region. It felt that its oil empire could come to an end." The Baltic seabed hosts three key types of communications: gas pipelines, fibre-optic lines and power cables.

All three have been severed in recent months. These could be dry runs for larger operations, given that the Baltic does not hold the largest concentration of such subsea communications. The density of underwater critical communications is higher in the North Sea, next to the Baltic.

This is largely due to a surge in offshore wind farms in the North Sea's shallow waters over recent decades. Their total capacity is estimated at 25 GW, which is equivalent to the output of 25 nuclear power units. To put this in perspective, Ukraine's peak consumption in recent years has been less than 20 GW.

A significant number of power cables, which transmit electricity from wind farms to the shore, run along the bottom of the North Sea.

This is why Russia has turned to sabotage, aiming to project a picture of the potential consequences should the Baltic states impose substantial restrictions on Russian oil traffic.

This could also be a kind of warning to Poland, which took over the presidency of the Council of the European Union on 1 January 2025. For instance, damage may be caused to the 600 MW power cable connecting Sweden and Poland, or to the Baltic Pipe subsea gas pipeline between the Norwegian sector of the North Sea and Poland, which has helped Warsaw diversify its gas supplies and allow it to abandon Russian gas. Additionally, Poland plans to build one of the world's largest offshore wind farms in the Baltic Sea, capable of providing energy to 2.5 million households.

The Kremlin's message to Poland is clear: with so much infrastructure along your coast, don't use your EU presidency to push anti-Russian initiatives. The recent events in the Baltic could be only the beginning, and if left unchecked, the frequency of such incidents may soon increase.

How to counter sabotage?

NATO countries are already stepping up the monitoring, patrolling and tracking of all ships in the Baltic Sea. This is the right thing to do, although it is impossible to put sensors on every kilometre of underwater communications or deploy constant maritime patrols.

Such measures would be costly and inefficient. Honchar proposes three options to force the Russians to stop destroying critical infrastructure. First, reciprocal actions are needed.

Something similar should happen to critical infrastructure on Russian territory. However, Russia, a continental state, has most of its critical infrastructure located within the country. Second, actions should be asymmetrical.

For example, in response to subversive activities in the Baltic, restrictions could be imposed on Russian oil shipments, thereby reducing the flow of petrodollars to its coffers. Moreover, Russia's shadow fleet of tankers, which mainly consists of outdated vessels, poses a global environmental hazard. These tankers have repeatedly caused kilometre-long oil spills, which have been recorded in different parts of the world, from Thailand to Vietnam, and from Italy to Mexico.

A fresh example is the disaster of two oil tankers that sank near the Kerch Strait in mid-December. The environmental damage caused by the spill of oil products from these two vessels is estimated at more than US£14 billion. Furthermore, the ships that sank in the Black Sea were carrying less than 10,000 tonnes of fuel oil, while tankers with a capacity of 100,000 to 150,000 tonnes regularly pass through the Baltic.

These larger vessels are typically fully loaded, meaning the impact could be far more severe. The third measure is to mirror the actions of Russia, which has repeatedly blocked the Black and Azov Seas under the pretext of military exercises. Honchar says: "They did this in 2020-2021 and there was no reaction.

Given that the Baltic is, in fact, a NATO and EU sea, [NATO and EU countries] can act in the same way: block the waterway between Finland and Estonia for civilian vessels. This can be done by organising a month-long exercise under the pretext of combating undersea sabotage. Then the Russians will feel it."

Otherwise, he believes, the frequency of sabotage incidents will rise weekly, potentially extending to the North Sea in the future. For this story, Ekonomichna Pravda interviewed Mykhailo Honchar, President of the Strategy XXI Centre for Global Studies, who has authored a separate study on the subject. Mykola Topalov

Translation: Artem Yakymyshyn

Editing: Shoel Stadlen