Alias Moses: Maksym Butkevych on 850 days in captivity, life on the edge of the abyss, and the miracle of his return

If Gabriel Garcia Marquez were to tell this story, it might begin like this. "Many years later, Lieutenant Maksym Butkevych, aka Moses, convicted of crimes he had never committed, was to wake up alongside three dozen prisoners in a penal colony in Luhansk Oblast and feel a sense of relief whenever he had nightmares." "You wake up terrified, and your first thought is: 'Oh, thank God, it was just a dream - actually I'm just in a prison camp.

The section, the barrack, captivity, the war - everything's fine,'" Maksym says, smiling, four months on from his release in a prisoner-of-war swap.

Advertisement:Human rights activist, philosopher, anarchist, journalist, antimilitarist, soldier - these are just a few of Maksym's many identities, enough for a whole cohort of remarkable individuals who may or may not all get along with one another. His friends nicknamed him "Maks 'Actually-It's-All-A-Bit-More-Complicated' Butkevych" in tribute to his dislike of simple answers to complex questions and easy paths to what only appears to be the truth. Maksym volunteered to take up arms in early March 2022.

Three and a half months later, he was captured by the Russians. Russian propagandists were frothing with excitement as they talked about the "valuable catch" Butkevych represented. The antifascist who had long endured hostility from Ukraine's far-right radicals was painted as a Ukrainian Nazi.

The human rights activist who had been helping refugees from Putin's Russia settle in Ukraine since 2014 was branded a Russophobe. And the committed antimilitarist? A "militant of the bloodthirsty Kyiv regime".

Thirteen years' imprisonment was the sentence handed down by a Russian occupation court in March 2023. He was released from Russian captivity together with 94 other Ukrainians on 18 October 2024. This is the story of Maksym "Moses" Butkevych, his many life choices, and his long journey to freedom - one that lasted far longer than his 850 days of captivity.

Maksym Butkevych: "In captivity, the scariest thing wasn't dying: it was doing something I wouldn't be able to forgive myself for.

Maksym Butkevych: "In captivity, the scariest thing wasn't dying: it was doing something I wouldn't be able to forgive myself for.

To me, physical death is not the end. But betraying myself, my values or the people who believe in me is true death."Photo: Oleksandr Ratushniak

A collection of identities

Maksym was born in Kyiv in the late 1970s, in an era when the pharaohs running his country were feeble. Back then they still had enough resources to build cardboard pyramids and throw dissidents behind bars, but not enough strength for anyone to truly believe in their greatness.

Can one be happy in slavery? Of course, provided you're a child and the love of your parents shields you from the lies that surround you. Even today, Maksym gives the impression of someone who grew up in an atmosphere of unconditional love.

The gentle gaze of a child who is loved is unmistakable, even when that child is now 47. "The love of my parents was instilled in me then and has supported me ever since, no matter where I am or what happens to me," Maksym says. As a child he dreamed of becoming an astronaut, until a heart condition made him realise it was a dream he would have to let go.

Luckily for him, it turned out that the cauldron of public life, bubbling over the fire of perestroika, was no less fascinating than outer space.

Advertisement:Maksym plunged headfirst into that cauldron in 1990, when he was 13. It was then that he came across a newspaper outlining the ideas of the newly formed political movements, one paragraph per faction. What intrigued Maks most were the views of the anarcho-syndicalists.

"I thought: interesting people, I need to find them. Protests were happening all around, so I went looking for the anarchists. I knew they carried red-and-black flags.

Eventually, I found some people with those flags. But they turned out to be not quite anarchists. It was either a faction of Rukh or the Ukrainian Youth Association, which I ended up joining.

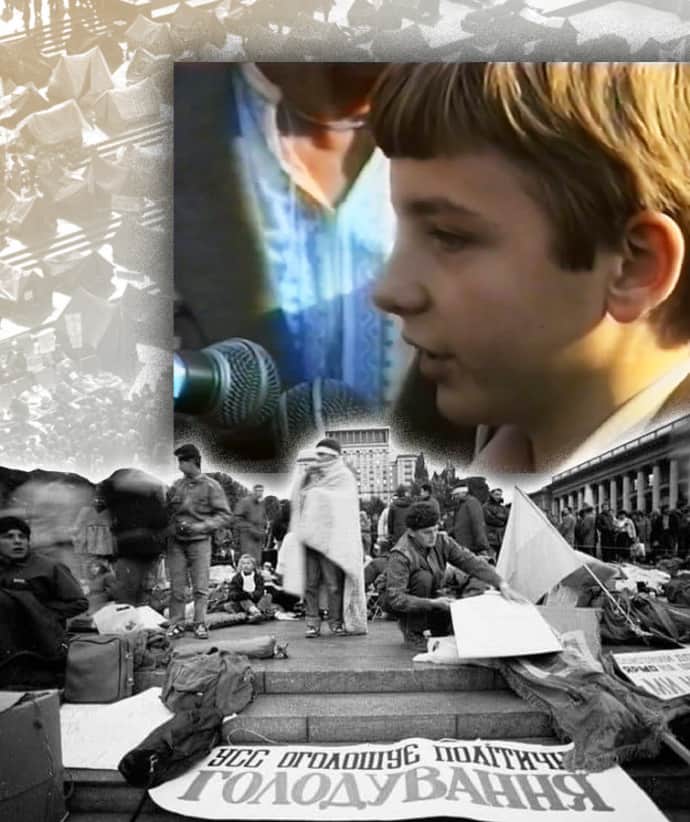

They even invited me in, despite my age. They took the fact that I'd taken part in the 1990 Revolution on Granite into account. I tried to organise a strike at my school, and I spoke at a rally in October Revolution Square [now Independence Square]." [The Revolution on Granite was a student protest in Kyiv against the Soviet government that led to democratic reforms and pushed Ukraine toward restoring its independence.]

That was my first taste of the idea that change was possible - change in the country, in society, in one's own fate. But it would come at a cost. This realisation shaped everything in my life that followed."

"We all understand this is only the beginning of the struggle.

"We all understand this is only the beginning of the struggle.

And we will fight on," 13-year-old Maksym Butkevych declared at his first rally during the Revolution on Granite.Photo collage: Andrii Kalistratenko

Maksym's long journey to becoming the person he is today involved many stops along the way. He's a philosopher and anthropologist by training, a human rights activist by nature, an international journalist, and a co-founder of Hromadske Radio and the No Borders Project, which sought to protect refugees and displaced persons. Yet he believes his most significant identity was shaped by his grandmother, a lecturer for the Soviet Knowledge Society who promoted atheist propaganda.

God must have a sense of humour, as it was on her bookshelf that he discovered the book that would later become central to his life - the Bible. When asked to rank his many identities, Maksym carefully guides you through the labyrinth of his self-perception. "Being a believer, a Christian, holds the greatest significance for me, though not in an institutional sense, but as an internal set of ideas.

Anarchist? I realise that to a lot of people who hold those convictions, I might not be an anarchist. I don't call for violent revolution, I've integrated into the state structure of the Armed Forces.

But if anarchism is about having an anti-authoritarian worldview, about recognising the dangers of power as dominance over others, about coordination being preferable to subordination and networks functioning better than rigid hierarchies - if all this defines anarchism, then I am an anarchist or at least anti-authoritarian. Human rights activist comes after that. This is about valuing human rights.

I fully understand their historical context, but I recognise their fundamental importance for every individual. This has been the main pursuit of my life for many years. Being Ukrainian is an essential part of me, though not more so than my other identities.

It does not separate me from the world, but rather adds to its diversity. And of course, since 2022 a new identity has emerged, one that will never leave me - I'm someone who has taken up arms, who is capable of fighting when necessary."

Advertisement:The birth of Moses

According to one story, the Old Testament Moses received his name from Pharaoh's daughter, who found the infant among the reeds on the riverbank. Maksym became Moses just before his first combat missions.

The company commander gave him the nickname after he signed up at the military enlistment office on 24 February 2022 and a week later put on the uniform of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Why Moses? Perhaps the commander was making a joke, recalling how Maksym had led a group of soldiers to the medical unit and they got lost.

He set off on a 20-minute walk and came back an hour and a half later. But the Old Testament Moses's gift for taking a long and winding path towards his goal isn't his only similarity with Maksym. "I would never compare myself to Moses, but there do seem to be some coincidences so far as the fundamentals are concerned," Maksym says.

"Moses is often seen as a leader and prophet who guided his people with a firm hand, sparing neither himself nor others. For a long time, I imagined him that way too. Then I came across a striking verse in the Book of Numbers: 'Now the man Moses was very meek, more than all people who were on the face of the earth.'

For me, this is an integral part of Moses's personality. This version of Moses, the man who not only led and punished but also protected his people and tried to shield them, is less familiar and less understood." The alias Moses stuck.

A comrade in his unit even asked him once, "Moses, what's your alias?"

When he was studying philosophy at university, Maksym had another nickname, Sobakevich ("Dogosopher"), though not because of the character in Gogol's Dead Souls. It stemmed from his admiration for the ancient Greek Cynics. The Greek word "cynos" means "dog", so "Dogosopher" was, in essence, a very philosophical name.Photo: Lesyk Urban

When he was studying philosophy at university, Maksym had another nickname, Sobakevich ("Dogosopher"), though not because of the character in Gogol's Dead Souls. It stemmed from his admiration for the ancient Greek Cynics. The Greek word "cynos" means "dog", so "Dogosopher" was, in essence, a very philosophical name.Photo: Lesyk Urban

As a pacifist, believer and human rights activist, why did he take up arms?

Western media outlets who interview Maksym often ask him this question. He usually answers that a Kalashnikov was the only way to defend human rights on 24 February 2022. "Of course I was not defending the state in the usual sense.

To me, the state is a creation of human minds and human hands, but it had become something different to what it should be. I was defending the people I love. I was defending people I didn't know but who shared my values.

I was defending people who did not share my views but believed that was no reason for us to hate one another. I was defending our right to choose at a moment when they were trying to take that right away. In essence, I was defending freedom, the freedom to choose the future."

Moses served in the military for three and a half months as a member of the 210th Berlingo Separate Assault Battalion. At first he was stationed in Kyiv Oblast on the Irpin front, but in June the unit was redeployed to eastern Ukraine. Maksym's platoon was ordered to set up positions near the settlement of Myrna Dolyna in Luhansk Oblast and observe Russian movements from there.

Maksym described two terrifying recurring nightmares that have plagued him all his life. "The first one is about being lost. I find myself in a house with many rooms or a labyrinth, searching for someone close to me but unable to find them.

The space keeps changing, yet I keep searching. In the second nightmare, I suddenly come face to face with a being that is trying to destroy me. Sometimes this happens when I'm talking to someone I trust and at some point I realise that this is not the person I know.

It isn't a person at all. It is something greater, more powerful than a human, merciless, devoid of any positive emotions, carrying nothing but pure hatred." On 21 June 2022, those nightmares became reality.

Advertisement:Instead of a desert: a field near the village of Myrna Dolyna.

Instead of God's chosen people: eight soldiers from the Berlingo battalion, led by their commander, Moses, who is trying to lead them out of an encirclement under mortar fire without communications or water. Instead of a burning bush: a radio which suddenly comes to life and speaks with the voice of one of the soldiers from a neighbouring unit: "You're surrounded, but if you follow the reference points I give you, you'll find your way out." "He led us to a field close to a strip of forest," Moses recalls. "When we were a few dozen metres away from the forest strip, my comrade told us that we had to stop, because we were in their sights.

He said he had been held captive by the Russians since the previous day. And that if we didn't lay down our arms now, we would be killed. We were an easy target in the middle of the field.

That's how we were captured. And then we ended up with this guy in a prison cell in a Luhansk detention centre. He was convinced he'd saved our lives.

Maybe he did, maybe he didn't. I don't know, I'm not his judge." Maksym's introduction to his new reality in the first few days of captivity was a history lesson from a Russian officer wearing a balaclava.

The officer would read out quotes from Putin's pseudo-historical research on Ukraine to the Ukrainian prisoners of war from his mobile phone. Anyone he pointed to had to repeat those passages word for word. If anyone stumbled or made a mistake, Moses was beaten with a wooden stick.

"Putin's version of Ukrainian history will stay with me as a scar on my shoulder for the rest of my life. Which I think is quite a beautiful metaphor, although it was not a very pleasant procedure," Maksym recalls.

Moses on captivity, fear, and the strategy of resistance

"As a Soviet child, I was brought up on stories about Pioneer heroes. They spat in the face of fascists, shouted 'For the Motherland!' and died heroically.

But as a human rights activist, I met people who had been tortured and realised how fragile a human being is. So I didn't know what to expect of myself in captivity. I found myself both stronger and more fragile at the same time.

Fear was a constant background for the first six months of my captivity. I'd never imagined before that fear could have such power over a person, that it could paralyse the will, desires, everything. What scared me most was the possibility of making the wrong choice, which would turn out to be a choice in favour of death.

In favour of something unforgivable. I was not so scared of dying, I was scared of doing something I wouldn't be able to forgive myself for or answer for - to myself, to God. For me, responsibility is about answering for my actions.

After about six months of captivity, I came up with a strategy of behaviour. When I was interrogated and told that I had to do something unworthy, I would refuse. Properly, politely, without getting personal, but I'd say that I wouldn't do it because it was not true, because I didn't agree with it, and ultimately because I was an officer of the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

And I'd immediately add that I was under no illusions - they could force me to do it. But I'd have to be forced, because I wouldn't do it myself. I understood that in this situation, their next step could be to use the tapik [TA-57, a field military telephone used to torture victims with electric shocks by attaching terminals to the earlobes, genitals, fingers, feet or tongue - ed.].

But I tried not to let fear take over, not to do something I wouldn't forgive myself for later. Surprisingly, they would be so astonished by my reaction that almost every time they did not proceed to physical pressure. I realise that in many ways I was lucky, because our other guys went through much worse things than I did.

I had less physical pressure, less bullying, less pain."

The battle for Frankl and the personal space of freedom

Many years later, in the library of maximum-security penal colony No.

2 in occupied Luhansk Oblast, Lieutenant Maksym Butkevych was to remember the Kyiv library his mother had taken him to as a child, where he would browse the shelves filled with tomes, curl up in a corner and read strange and wonderful books. "I'm one of those people who remember the smell of books. So when I got to the library there [in the penal colony], I felt that of all the places around me, this was the least threatening and dangerous place for me," Moses recalls.

It was around a book that the epic battle for Butkevych's personal space of freedom in captivity unfolded. Maksym was sent a book by Viktor Frankl, A Psychologist in a Concentration Camp, but the vigilant guards were so exercised by the words "concentration camp" in the title that they refused to give it to him. "I spent the next month pestering the colony's management about getting my book.

The whole barrack was watching me try to get my hands on Frankl. In the end, the acting head of the colony said that he would personally read the book, find out everything he could about the author, and if there really was nothing forbidden in it, he'd give it to me. I said: 'Please make sure you read it.

I think you'll find it very interesting.' I hope he did read it." Books, letters and prayers which he composed in his mind became a space of internal resistance for Maksym. When he was finally given permission to write letters from the penal colony in spring 2024, he received a "request" from the censors: "Tell him to write less - we don't have time to read it all."

"I replied: 'I'm sorry, but you've locked me up and now you'll have to read my letters: about the connotations of ancient Greek words, about the neurophysiology and mechanisms of pain and fear, about the peculiarities of the Church Fathers in terms of social issues, about what went wrong with the Russian Orthodox Church."

Maksym Butkevych: "One of the guards in the penal colony said: 'Moses, when are you going to get your people out of here? Get them out now. I really want you to get out of here as soon as possible and take your people out."Photo: Emile Ducke

Maksym Butkevych: "One of the guards in the penal colony said: 'Moses, when are you going to get your people out of here? Get them out now. I really want you to get out of here as soon as possible and take your people out."Photo: Emile Ducke

At the end of August 2022, Maksym and another prisoner of war were taken to Popasna and Sievierodonetsk by the Russians for their trumped-up crimes to be "documented".

They were transported in the back of a Patriot UAZ, handcuffed to each other and chained to the bars. It was sweltering hot in the car and the windows were closed, almost like summer in the Judean desert. As they were driving along, Maksym remembered that he hadn't finished saying his morning prayers.

Among those to whom he mentally addressed himself was the biblical Moses. "I asked that our people would come out from under Pharaoh's yoke and reach the promised land. That the modern-day Pharaoh, the ruler of the Russian land, and his associates would be brought to justice for what they are doing, that they would be scattered like dust in the wind, and vanish and perish like dew in the morning sun.

Of course our guards didn't know about this, but even if they had, they couldn't have done anything," Moses recalls. After he was released, Maksym was given a T-shirt with a quote from Frankl on it: "The one thing you can't take away from me is the way I choose to respond to what you do to me. The last of one's freedoms is to choose one's attitude in any given circumstance."

The final battle for Frankl's book did not take place in the penal colony: Maksym had been due to receive the book on Monday, but the day before, he was taken out of the camp for a prisoner swap. "But one of the books I received on the outside during my first week of rehabilitation was a Ukrainian translation of this very book by Frankl. So I think at least in this way, I won that battle."

Advertisement:Why and for what purpose?

In times of trials, when an atheist usually asks himself "Why?", a believer tries to understand "For what purpose?"

Have his years of captivity brought Maksym any closer to answering that second question? "In dark times, the question of theodicy comes to the fore for many people. Where was God?

Why did he allow this to happen? I was waiting to see whether this question would arise for me. It didn't at all.

I wasn't interested in God's responsibility. You don't have to shift the responsibility for your own choices onto someone else, whether that's another person or God. I was interested in my own responsibility: what I can do, what I have done (or will do) right or wrong.

Each of our present choices shapes our future choices. For me, my time in captivity was about shaping the next me, about finding out what was really important to me, about building my priorities. To understand and feel this, I had to get to where I was and go through what I was going through.

I was grateful to have had the opportunity to comprehend this. And I just asked for strength to be able to walk this path with dignity, and for me to control my fear, not for it to control me. Perhaps that was the most important thing."

War is always a time of simplification. Where are the red lines for Maksym "Actually-It's-All-A-Bit-More-Complicated" Butkevych today that he would not want to cross in this simplification, under any circumstances?

Advertisement:Moses on the mirroring of brutality, dehumanisation, and generalisation

"I'm not the type of person to condemn anyone or preach to anyone, but for me personally, I consider three things unacceptable. The first is attempting to maximise the 'eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth' law. They hurt and rape and kill, so we should do the same.

When our guys would be having conversations outside the barracks in the penal colony, sometimes one of them would say: 'You know their prisoners who're being held in Ukraine - are they put through anything like what we've been through? I hope so.' Usually, before I could open my mouth, one of our guys would say: 'No, we can't do that.

Our prison camps are probably open for inspections by international organisations, and because of that, they have to keep Russian prisoners of war in different conditions.' The Russians convicted of their crimes must be punished, but not tortured. If that rule is violated, I'm prepared to defend Russian prisoners of war tooth and nail.

We must not be them - in order to remain human, and in order for our struggle to remain a just struggle. Otherwise, what is it for?

Maksym Butkevych: "While in captivity, I got the feeling that there are no coincidences at all. There is a fabric of life that is woven in such an amazing way.

Maksym Butkevych: "While in captivity, I got the feeling that there are no coincidences at all. There is a fabric of life that is woven in such an amazing way.

Everything was a part of this fabric, everything made sense, even if it was not always immediately apparent."Photo: Emile Ducke

The second thing is total dehumanisation. War always involves dehumanisation, especially when it comes to people with weapons in their hands. Unless someone has psychological characteristics that are now most often defined as pathologies, then in order to kill another person, they need either an affect or an extremely serious motive.

In any case, first of all, that other person must be dehumanised. However, it's one thing to dehumanise an enemy on the battlefield, but quite another to start dehumanising the entire community identified with the enemy. At that point it no longer matters whether they're soldiers or civilians, men, women or children.

When collective dehumanisation takes place, especially when it's done by people who have no direct connection to the battlefield, I find it completely unacceptable. The third thing is generalisation. I don't believe in collective responsibility based purely on belonging to a community defined by ethnicity or other aspects of identity, especially those that people have no control over.

If we're talking about all ethnic Russians, regardless of where they live, or everyone who speaks mostly or only Russian - no, I do not believe they bear collective responsibility. But if we're talking about citizens of the Russian Federation, the question 'What have you done to stop this?' is one that applies to every single one of them. Even to those who haven't killed anyone, have not fought, and have not worked in defence industries.

Because they are part of a society that keeps Russia's economy afloat, pays taxes, and upholds the illusion of normality in the midst of the horrific disaster unleashed by their government. Naturally, this implies a certain degree of responsibility. Because that money funds the production of weapons.

Because that 'normality' enables the killing of other people to continue. While in prison, I read several articles by Hannah Arendt, one of which dealt specifically with the issue of collective responsibility. She writes that perhaps the only way to escape it as far as the citizens of a particular state are concerned is to renounce one's citizenship.

There is no other way. Either you renounce your citizenship, or you share that responsibility with others."

Hugs and triggers

Maksym describes his state of mind in captivity like this: "At some point in that cell at the Luhansk pre-trial detention centre, it occurred to me that we were like insects trapped in amber. Outside, new geological layers were forming, but the insects remained frozen at the moment when the resin had caught, engulfed and immobilised them.

I had become frozen in June 2022." Maksym was finally freed after 850 days of imprisonment. Four months on, I ask him what brings him the most joy in this new world - and what he finds most annoying.

He gets great joy from friendly physical touch and hugs, something he sorely missed in captivity. "Any physical contact in prison or a penal colony is a threat, always a prelude to something worse - beatings, violence, or punishment. I've had so many hugs since I was released.

At first I joked about having a sense of tactile deprivation, but then I realised that it was actually true. And even now, I'm genuinely happy whenever someone hugs me." There are two things that trigger him.

The first is anything to do with mobilisation and, more broadly, the changing attitude of some sections of society towards the war and their role in it. "Perhaps this is the one area where Russian propaganda has managed to unsettle us, because it has played on the strongest human instinct - the instinct of self-preservation." The second trigger is personal - it surfaces whenever Maksym feels that someone is trying to impose a choice on him or restrict his freedom to choose, even unintentionally, even with the best of intentions, by offering unsolicited advice: "You know, you'd be better off doing this," "It's best to choose that," "You should consider this for your future."

"My first reaction is: don't tell me what's best for me. Even if I make a mistake and choose the worse option, at least it will be my choice. I've never felt such a strong need to make my own decisions as I do now.

It can really trigger me, and then I have to apologise for my reaction. Fortunately, so far people have been understanding." Captivity still catches up with him in his dreams, though he rarely remembers them.

"If I wake up overwhelmed with happiness, it's only then that I realise I must have been dreaming about being in captivity," he says.

Life as a miracle

What has stayed with Maksym to this day is his sense of a miracle. "The fact that I survived and returned is a miracle. It's hard to live with this awareness, knowing that circumstances 'wear it away' and that over time, it fades and gets lost.

But it can stand up for itself and remind me - most often through other people. It's a pity I never got the chance to meet Ihor Kozlovskyi [a renowned Ukrainian scholar and theologian - ed.]. We walked the same paths, but they never crossed.

It was only in the summer of 2024, while I was still in the penal colony, that I learned of Kozlovskyi's passing. Suddenly I felt an immense sadness, as if something important had been taken away from me. When I returned, several people unexpectedly said words to the effect that 'We lost Kozlovskyi, but we've got you back.

The space has been filled again. Now it's your turn to speak out about the things that matter.'" I remind Maksym of something he said in an interview in 2017: "I personally don't need just any Ukraine.

Independent at any cost, independent just for the sake of it, and then we'll see. No. I need Ukraine to be a country of free people, a project, a society striving toward an ideal - a place where everyone can live without fear, regardless of who they are or what they believe."

I ask him if he still stands by those words. "I do. Because an authoritarian, chauvinistic, xenophobic Ukraine would just be 'another Russia', no matter what it called itself.

It might speak a different language and outwardly nurture different traditions, but its values would remain the same. For me, Ukraine is about values. We are different at the foundation - not in our walls, not in the carvings on our window frames.

We are different at the foundation, not genetically - definitely not - but through the choices we have made throughout history. If we suddenly changed and became like Russia, to me, that would mean we would have lost, no matter what we called ourselves. I don't need a Ukraine that we can lose to ourselves, keeping only the name and not the values."

A Scheherazade for our times

Over the past few months, Maksym has frequently travelled abroad - New York, Washington, Brussels, Strasbourg, Munich, Copenhagen - talking about what he endured in captivity.

He does everything he can to make people in other countries feel that this distant war is their own. With his ever-gentle smile, Maksym recalls the words of a colleague and friend: "Scheherazade told stories to survive. We are doing the same."

He radiates calm, even when discussing things that drive others to despair - such as Donald Trump's latest statements. "For what purpose?" is still the key question for Maksym, even now that he is free - in a world that increasingly resembles a dystopia. "Many who once hoped for a black-and-white division of the world - an almost Manichaean split between the forces of light and darkness, our allies and Russia with its allies - have now realised that things are far more complicated and far worse.

That some of our allies are not so different from our enemies in terms of their priorities and political behaviour. That others are too hesitant, too slow, even though they know this hesitation could end in tragedy. But this entire situation brings us back to ourselves.

Some may be hoping that the 'big guys' will come and fix everything. They're not going to. And they're not that big either."

Maksym Butkevych: "Life, meaning, freedom, and love - things we try to separate in our minds - are actually one and the same: the fabric of life."Photo: Lesyk Urban

Maksym Butkevych: "Life, meaning, freedom, and love - things we try to separate in our minds - are actually one and the same: the fabric of life."Photo: Lesyk Urban

We return to the central story around which, one way or another, everything on Maksym's journey revolves - his escape from captivity, and his rediscovery of himself.

I ask him what point he thinks we are now at on this path. "On one hand, we are crossing the sea with Pharaoh's army in pursuit. What's happening is terrifying, and no one knows how it will end.

But we keep moving forward because we have to believe. On the other hand, I'd like to think that we are already near the Promised Land. At the very least, we've passed the stage where, to put it in modern terms, 'the people are confronting Moses' - when the primary demand was always directed at others: 'Give us this, give us that.'"

Biblical scholars have calculated that the 40-year journey that the chosen people made from slavery in Egypt to the land flowing with milk and honey should have taken no more than 10-11 days if they had travelled directly. But as it turns out, reality is a bit more complicated. And takes a lot longer.

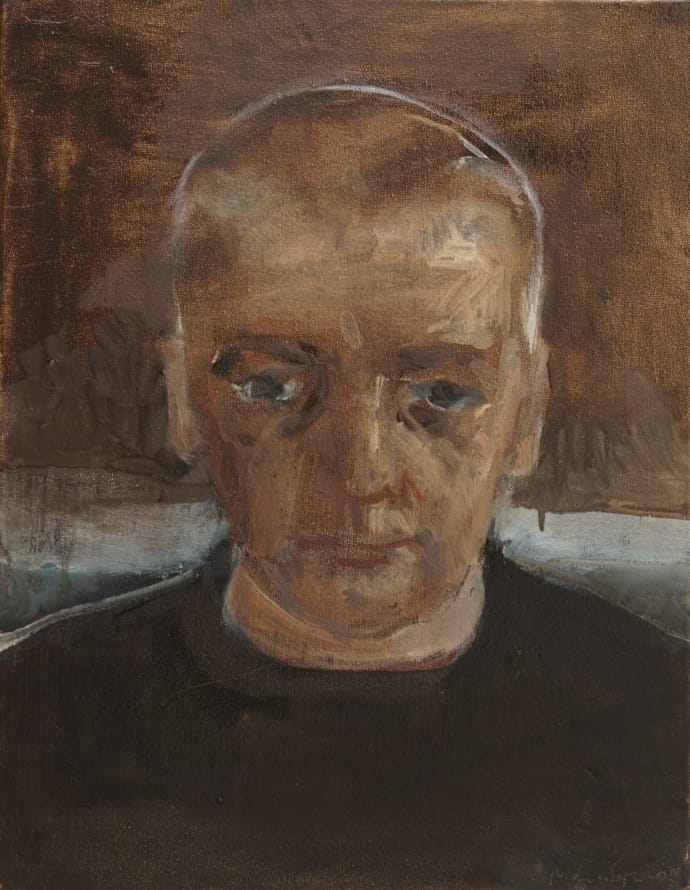

A portrait of Moses

Many years later, Lieutenant Maksym Butkevych, alias Moses, would step out of his barracks on the first floor of the maximum-security penal colony, always remembering the same painting - Bird over Birkenau by Matvii Vaisberg.

"I saw part of the colony as if from above," Maksym recalls. "Of course, it wasn't a concentration camp, just a high-security zone. But there was something deeper than mere external resemblance. Something that makes all concentration camps, penal zones, penal colonies and prisons alike - places where people are punished not for crimes, but for belonging to a community, for their thoughts, for their values."

Bird over Birkenau by Matvii Vaisberg

Bird over Birkenau by Matvii Vaisberg

When Maksym was released in October 2024, he wrote to Vaisberg and told him he would be honoured if the artist would paint his portrait.

Vaisberg agreed instantly - who else but him, known for his works inspired by Old Testament stories, should paint Moses? "We spent several hours in his studio. We talked about some serious matters, but also about simpler things, with humour.

And when he'd finished the portrait, he suggested I take a look. To be honest, I approached it with some apprehension. And then, it took my breath away.

I wouldn't say the person in the portrait was looking at me. He was staring into the abyss. Not into emptiness, but into the abyss itself.

He had to look into it - not because anyone was forcing him to, but because he had to. To hold on to his humanity. To understand the edge we are constantly treading.

And to keep himself from falling in. It turned out to be an incredibly human portrait."

The portrait of Maksym Butkevych by Matvii Vaisberg

The portrait of Maksym Butkevych by Matvii Vaisberg

Many years later, Butkevych was to meet his namesake, the prophet Moses, and rejoice in his warm embrace. Not the Moses of Michelangelo's sculpture, with horns on his head, but the "meekest of all men".

"I always wanted to have your ability to distinguish what is truly vital from what is secondary," Maksym-Moses was to say. "I'm not sure I ever succeeded, but I wanted to. I always wanted to choose my own path. But I'm human, and humans make mistakes.

That's why it was important for me to feel that wherever I went, God was with me. To walk in the ways of the Lord, as the Bible says. That's what guided you throughout your life.

I desperately wanted to have your courage to argue with God. And the strength to ask that the responsibility for my people's mistakes would fall on me alone." Moses was to listen, and perhaps reply: "Brother, it's actually a bit more complicated than that...

But listen, I've been recommended a nice little place nearby. It won't be quick, but I promise it'll be interesting. Come on, let's go."

Author: Mykhailo Kryhel

Translation: Tetiana Buchkovska, Yelyzaveta Khodatska and Violetta Yurkiv

Editing: Teresa Pearce and Shoel Stadlen