“We're tired of beating you Ukes”: Azov fighter Yuzhnyi on his two years of torture in Taganrog, prison humour, and his own system of survival

"Glory to Ukraine, guys. If anyone makes it home, tell them what's happening in Taganrog." - Mykhailo Chaplia was in Pre-Trial Detention Centre No.

2 in Taganrog, Russia, when he came across this message, origin unknown. Now is not the time to reveal exactly where it was encoded.

Mykhailo, a tall and wiry man from Kharkiv with a sharp sense of humour, reminded me of the main character of Ivan Bahrianyi's The Garden of Gethsemane [a 1950 novel which drew on the author's own experience of a Soviet labour camp]. Some of the events described in the book are experiences Mykhailo has lived through. The Russians starved him, tortured him with electric shocks, broke his ribs, locked him in a tiny basement, and attempted to extract absurd "confessions" from him.

Advertisement: Advertisement:Mykhailo Chaplia, alias Yuzhnyi, ultra football fan of FC Metalist and Azov officer, devoted nearly ten years of his life to military service.

He started out in tank reconnaissance in March 2015 and became an armoured personnel carrier driver in 2017, and later a staff officer. He defended Mariupol, and in May 2022 he left the Azovstal steelworks for what the Russians called "honourable captivity". For the first four months, he was held in a prison camp in Russian-occupied Olenivka, Donetsk Oblast.

Then, at the end of September 2022, he was transferred to the pre-trial detention centre in Taganrog, about 120 km (74 miles) east of Mariupol, where he spent 24 months.

Before the full-scale invasion, Mykhailo Chaplia served in tank reconnaissance and as an APC driver, and later became a staff officer

Before the full-scale invasion, Mykhailo Chaplia served in tank reconnaissance and as an APC driver, and later became a staff officer

Taganrog is not just the name of a city - it's synonymous with the conveyor belt of torture designed by Russia. It's where the Russians break people, beating confessions to fictitious crimes out of them until they are ready for a show trial. "Taganrog is the perfect place for Russians because there's no oversight," Yuzhnyi says, recalling the brutality of the guards and investigators. "Dostoyevsky once used the term 'administrative ecstasy' - when people get drunk on power.

That's exactly what it is." Yuzhnyi talked to Ukrainska Pravda. Zhyttia about his two years of torture in Taganrog, the "Telegin system" that helped him get through, the prisoners' gallows humour, and the massive surprise he got after his release.

"When you arrive in Taganrog, they pound you like a meat patty"

Taganrog, September 2022.

When new prisoners arrived, guards from every shift would gather alongside Russian special forces for their "reception". Armed with batons, sticks and tasers, they were tasked with beating several hundred prisoners as they ran down a corridor. "On the very first night, guys' bodies were being dragged away on bedsheets," Mykhailo recalls.

Yuzhnyi was relatively lucky that time - he "only" ended up with cracked ribs and broken fingers. But many of his comrades suffered much worse - their broken ribs punctured their lungs. Some of the prisoners died of pneumothorax.

Initially, Mykhailo was held in the Olenivka prison camp, but in late September 2022, he was transferred to Pre-Trial Detention Centre No.

Initially, Mykhailo was held in the Olenivka prison camp, but in late September 2022, he was transferred to Pre-Trial Detention Centre No.

2 in Taganrog.Photo from Olenivka

"When you arrive in Taganrog, they electrocute you, pound you like a meat patty, and tread on you with their boots. It doesn't matter whether you scream 'I'll sign everything' or stay silent - they beat you anyway, without asking questions. You have to do 200 to 500 squats.

Your muscles are inflamed and you physically can't do anymore, but you do it anyway. Then you go out for a 'walk' - and before that, they beat you again. You have to walk quickly and in perfect sync.

If you don't, they 'teach' you very fast," Mykhailo recalls. When Yuzhnyi arrived in Taganrog, suddenly the regime at Olenivka looked like a children's summer camp in comparison. Though brutal, it had at least been predictable.

The prisoners there could walk around the territory, talk to each other, and even see the sun. All of those "privileges" vanished at Taganrog. Prisoners had to walk in an "L-shape" - head down, hands behind their back.

Raising their eyes was forbidden, and so was speaking without permission. Even if they were asked a question, they first had to say "Permission to answer, citizen officer."

Advertisement:Every movement - walks, showers, interrogations - was accompanied by beatings, and not just from the guards, but Russian special forces as well. "Whenever a new unit of special forces arrived, the first thing they'd ask was: 'Where are the Azov fighters?' The guards would point us out and say, 'There they are, look.' I was an Azov officer from Kharkiv, a staff officer, and a football ultra, so I got the full treatment.

A dog would grab you in the corridor, and if you flinched, they'd shock you. One of the guys was bitten by the dogs until he bled during his 'reception' and his uniform was torn to shreds. When he asked for a new uniform, the 'citizen officer' sneered: 'Oh wow, what's wrong with your arms and legs?

Why are you covered in blood?' The other guards laughed. Then they said, 'Hey, why've you ruined your uniform?' - and started beating him for that. When they were ordered to stop beating the prisoners with their fists, they switched to torturing them with electric shocks.

I remember one guy near me who couldn't take it anymore and just screamed, 'Please, I'm begging you, just punch me and kick me instead.' That's what they reduced people to."

"You have no choice but to eat shells, scales and tails": everyday life

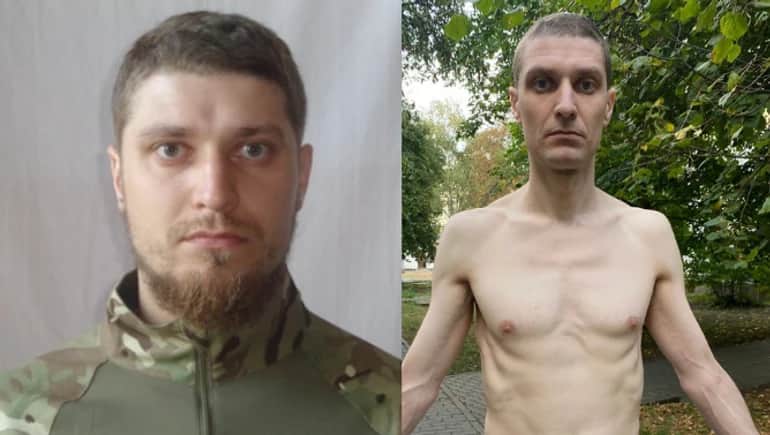

In Taganrog, prisoners immediately underwent a brutal "reception". Not everyone survived.Yuzhnyi before and after Russian captivity.

In Taganrog, prisoners immediately underwent a brutal "reception". Not everyone survived.Yuzhnyi before and after Russian captivity.

A floor consisting of twelve planks, a bench, a table, and a toilet. That was the basement cell where Yuzhnyi spent 17 of his 24 months in Taganrog.

The guards' latrine was in the corridor opposite the cell. They deliberately left it unflushed. Next to it was a shower, which became yet another site of torture.

The prisoners were taken there once a week under blows from batons and tasers. But if they were "lucky" enough to be summoned for interrogation at that time, they would have to wait another week for their next chance to wash. The cells always stank of urine and sweat.

There was dampness, foul smells and mould everywhere. Yuzhnyi was lucky - amazingly, he never contracted tuberculosis. "There was no soap, no toilet paper.

At first we had one cup for two people - you drank from it and used it to wash," Mykhailo recalls. The prisoners dreamed about food constantly. Yuzhnyi craved borshch, syrnyky (curd cheese pancakes), fried duck, crucian carp, burgers, apples, oatmeal cookies and kefir.

Advertisement:They had to eat very different "delicacies": sauerkraut with water, semolina porridge with raw herring or, if they were lucky, with cooking fat.

Before captivity Mykhailo weighed 105 kg (231 lb; 16 stone 7 lb); when he was released, he was down to 58 kg (128 lb; 9 stone 2 lb). "They feed you worse than a dog. But you have no choice but to eat shells, scales and tails.

You have to eat it all up very fast, wash your dishes, and hand them over to the 'balandyor' [an inmate who distributes the meals]," he recalls. For a while, the prisoners managed to scratch short messages into the bottoms of their bowls. These words gave them more strength than the watery gruel they were fed.

But then the prison wardens found out and they began scrubbing the messages away.

"An addict, a professor, and a Territorial Defence fighter": cellmates

Mykhailo went through hell in the Russian torture chambers because he was an Azov soldier, an officer, a native of Kharkiv, and a football fan.Mykhailo with his wife Sevinj

Mykhailo went through hell in the Russian torture chambers because he was an Azov soldier, an officer, a native of Kharkiv, and a football fan.Mykhailo with his wife Sevinj

The special block cells in the basement held a mishmash of prisoners, both military and civilians. There was Volodymyr Baraniuk, the commander of the 36th Marine Brigade, and the mayor of Kherson, and a Colombian who didn't understand a word of Russian, and dozens of others who had simply been in the wrong place at the wrong time. "For a while, I shared a cell with a drug addict from Luhansk who had hepatitis, a Territorial Defence fighter from Mariupol with lung cancer, and two men from Melitopol - one was a professor, and the other couldn't tell his right from his left.

That's how absurd it all was," Yuzhnyi says. The man from occupied Luhansk was well on in years and suffering from hepatitis. He hoped the Russians would believe he was innocent and release him, but their so-called justice knew no mercy.

"The drug addict, Serioha, was thrown into my cell. He'd been accused of being an artillery spotter and brutally tortured. He had two taser burn marks so big that you could fit your little finger inside.

His legs were purple and so swollen that an infection had already set in. He'd started wetting himself, but they didn't give a shit." Mykhailo looked after his cellmate for about a month.

He begged the guards not to take him out into the corridor, carried him on his shoulders, and helped him wash himself. But there was no soap, which made it twice as difficult.

Advertisement:"I'd call the bathhouse attendant 'citizen officer' and he'd tell me to f**k off - this happened over and over again, at least ten times. But I was getting beaten constantly anyway, so I just kept asking.

Eventually I annoyed him so much that he chucked a bar of soap into my cell - it was tiny and covered in pubic hair, but at least it was something," he says. Ultimately Yuzhnyi paid for his kindness to his cellmate. He was beaten, and Serioha was moved to another cell.

"We're tired of beating you Ukes": the guards

In Taganrog, the Russians beat the prisoners daily and often denied them medical treatment.Yuzhnyi and his comrade (alias "Nikopol") during rehabilitation

In Taganrog, the Russians beat the prisoners daily and often denied them medical treatment.Yuzhnyi and his comrade (alias "Nikopol") during rehabilitation

Walls have ears.

It was in Taganrog that Yuzhnyi fully grasped the meaning of this phrase. When the special block was quiet, the walls of his cell "listened" to Mykhailo's prayers, while he listened to the prison guards' conversations - about their side hustles, visits to prostitutes, and the hanging of Ukrainian female prisoners. The silence was occasionally broken by the screams of prisoners or loud Russian music blaring out - songs like White Army, Black Baron or Arise, Great Country and other Bolshevik-era hits.

The music was a separate form of torture. Once it played all night. The guards would ask the prisoners, "Do you like the music?" - and they had to reply "Yes." But in the brief moments of silence, Yuzhnyi learned to pick up on every rustle from the floors and to distinguish the different tones in the torturers' voices.

"You try to recognise them by their voices, guessing who's coming on shift. You imagine what they look like, their build. You learn to sense every breath and every movement so you know how to behave.

It's like reading a fascinating book - one you desperately want to finish, but can't," Yuzhnyi recalls. The female guards were just as cruel as the men. They would torture prisoners for show to impress their "colleagues".

"I'm used to using feminine job titles in Ukrainian, so I was genuinely shocked at having to address a female guard as 'citizen officer'. I wanted to use the feminine version of the word, but when another guy did that, she snapped 'This isn't your Gayrope'," Yuzhnyi says. Out of all the guards, there was only one - quite an authoritative figure - who didn't harm the prisoners, although one day even the most zealous of the torturers told the prisoners, "We're tired of beating you." But they didn't stop.

"In Taganrog you're not allowed to look out the window. But in one of the cells, someone kept staring outside. The Russians got so frustrated that they said: 'Are you Ukes completely stupid?

We beat you every single day, five or six times a day. Our hands and feet are sore already. Do you not understand that you're not allowed to look outside?

We're tired of beating you'," Yuzhnyi says. The medical staff were slightly more humane than the guards. One female doctor even let a prisoner sit on a bed instead of standing in his cell - he had been injured in the terrorist attack on Barrack 200 [at the Olenivka prison camp where Ukrainian POWs were tortured and killed in an explosion in July 2022- ed.].

But access to even the most basic medical care depended entirely on the guards' moods. Yuzhnyi learned to recognise the most sadistic ones and never asked for anything when they were on shift.

Advertisement:"If you ask for a medic, they'll ask what hurts. If it's a bad shift, don't even bother asking.

If you say your stomach hurts, they'll start punching you in the stomach. 'Does it still hurt?' 'No, citizen officer.'

That's their idea of medical treatment."

"You have to think up a crime for yourself": investigations and trials

The Russians tortured Ukrainian prisoners of war into "confessing" crimes they never committed.Photo: Mykhailo in Mariupol

The Russians tortured Ukrainian prisoners of war into "confessing" crimes they never committed.Photo: Mykhailo in Mariupol

"We need the truth," the officers from the Russian Investigative Committee would say when conducting their brutal interrogations in Taganrog. "They need believable stories. They didn't want us just to sign a piece of paper with fake charges - they wanted us to think up our crimes ourselves," Yuzhnyi explains.

At first they tried to pin civilian murders on Mykhailo, but he had been an armoured vehicle driver, not a shooter. Then they tried to accuse him of setting fire to the Trade Unions House in Odesa on 2 May 2014. But he hadn't even been in Odesa that day - something he had repeatedly stated in interviews with Russian propagandists before ending up in Taganrog.

"I endured everything and refused to sign anything, but I think they just couldn't find 'witnesses' against me," Yuzhnyi says. "The truth is, they'll fabricate whatever they want if they can force another prisoner to testify against you. It has nothing to do with your willpower... There, you finally realise that they humiliate, beat and torture you simply because you're Ukrainian.

People who think 'I'm a civilian, this doesn't affect me' are wrong. To the Russians, a civilian is a spotter and a soldier is a terrorist. All Ukrainians have to go through filtration - they'll strip you down and wring you dry.

The Russians will hang you upside down and electrocute you with tasers and field telephones. Both men and women - it makes no difference to them." Mykhailo knew he might not live to see a prisoner exchange, but he remembered Bruce Lee's words, "Be water," meaning adapt to the circumstances you're in.

Mykhailo mentally prepared himself for two and a half years in captivity. That's roughly how long it ended up being. "Those who kept telling themselves they'd be exchanged tomorrow were wrong.

Sadly, there were some suicides. About two weeks before I was released, a guy in the next cell found a shard of something under the doorstep and slashed his wrists and stomach. He survived by some miracle - they resuscitated him and moved him somewhere else.

It's the worst feeling when you try to lift someone's spirits, saying, 'We're all going to get out of here, brother', only to find out later that one slit his wrists, another one couldn't take it... I never considered suicide because I wasn't interested in dying. I wanted to walk out of there as the victor.

What kept me going was the thought that I was going to get out and live the rest of my life, while they'd be stuck there wallowing in their own filth," Mykhailo recalls.

"I asked for Alexei Tolstoy - they brought me Leo": the Telegin-Chaplia system

During his captivity, Yuzhnyi read a lot of Russian classics - Dostoyevsky, Pushkin, Lermontov. "When there was a decent shift, we could swap books. But not always.

Once I asked for a Bible - they brought me Mayakovsky. I asked for Alexei Tolstoy, and they brought me Leo Tolstoy," Yuzhnyi says. He had become interested in the Russian writer Alexei Tolstoy (a distant relative of Leo Tolstoy) back in Olenivka, where he read his trilogy The Road to Calvary.

One of the characters, Ivan Telegin - a former nobleman and officer - is arrested by both the Bolsheviks and the Whites. To stop himself from going mad in prison, Telegin would do 100 exercises in the morning, in the afternoon and before bed. In captivity, Yuzhnyi saw himself in Telegin and decided to do the same - training every morning, afternoon and evening.

Mykhailo invented the name "the Telegin system" when he asked his brothers-in-arms who were being released from captivity to "say hello to Docent from Telegin", because Vladyslav Dutchak, alias Docent, had also trained with Yuzhnyi back in Olenivka. The system came in handy in Taganrog. In a cramped cell where he could barely turn around, Yuzhnyi did planks, push-ups and squats.

To get through interrogations, Yuzhnyi created his own survival system, inspired by the character of Telegin from Russian literature.Docent and Yuzhnyi in Mariupol

To get through interrogations, Yuzhnyi created his own survival system, inspired by the character of Telegin from Russian literature.Docent and Yuzhnyi in Mariupol

Yuzhnyi knew the guards would torture him with gruelling exercises during inspections or interrogations, so he toughened himself up so much that eventually it became easier for him to repeat them.

And the self-discipline helped to keep his spirits up. "The body gets used to exhaustion. But this requires a special philosophy - not just doing squats for no reason.

If you do 20 squats like that, you'll get out of breath and your knees will start to crunch. I did these exercises to show that people can do anything. I had a goal - to survive.

I knew I'd have to go to the next inspection anyway and I'd be forced to do exercises, but I could stand it. Each time I did it better and better. They said to do 200 squats, and I did it.

They told me to do the splits, and I did. They were amused by it, they had fun. One of them was boasting to another one: 'Look how I taught him.'

It's hard and it's painful, because my joints were broken. Of course, that inspired them to test my pain threshold further. But then they saw that I made no sound, and they weren't interested any more," Mykhailo says.

Gallows humour

As well as the "Telegin system", praying and humour helped Mykhailo survive in captivity.Yuzhnyi after his release

As well as the "Telegin system", praying and humour helped Mykhailo survive in captivity.Yuzhnyi after his release

Even in the hell of Taganrog, there were sometimes funny situations.

Sometimes the POWs got the chance to make fun of the guards. The main thing was not to let them realise it. Once Mykhailo made a good joke when the Russians asked if he'd heard of Yevgeny Prigozhin, the former head of the Wagner Group.

"I found out about the capture of Bakhmut when they were shouting "We've taken Artemivsk!" [as Bakhmut used to be known]. The food slot in our cell door opened, and they shouted: 'Do you know who Prigozhin is?'

'Permission to speak, citizen officer.' 'Granted!' 'He's the husband of that singer, Valeriya.'

'Are you f**king crazy?' [Valeriya is married to Russian music producer Iosif Prigozhin.] 'I don't know, citizen officer.' Yuzhnyi also gave nicknames to some of the torture chamber staff.

For example, the "balandyor" was called Kolya-pyramid, because he used to stack the plates of food in a pyramid, one on top of the other.

The prisoner swap. Freedom. The cafe

On 13 September, Mykhailo Chaplia and 48 other Ukrainian prisoners came home13 September 2024.

On 13 September, Mykhailo Chaplia and 48 other Ukrainian prisoners came home13 September 2024.

Ukraine brought back 49 prisoners, and Yuzhnyi was among them.

"Where have you guys come from?" "We're back from captivity." "Is Azov coming back?"

"Yes it is." Yuzhnyi and his brother-in-arms, alias Nikopol, can be seen in a video that immediately went viral. Thin but smiling, they hold the Ukrainian flag.

Mariupol defenders Nikopol, Nava, Bilyi and Yuzhnyi with his wife Sevinj at the Charlie Chaplia cafe.Civilian life

Mariupol defenders Nikopol, Nava, Bilyi and Yuzhnyi with his wife Sevinj at the Charlie Chaplia cafe.Civilian life

Mykhailo had a feeling that the prisoner swap was coming.

In the summer of 2024, there were six or seven people left at the post where he was detained. The Russians started taking POWs out of Taganrog. At the time, Mykhailo thought his brothers-in-arms were being taken to be exchanged, but in fact, most of them were going to be tried and sent to prison.

On one September day in 2024, the guards told Yuzhnyi to come out and get dressed. They gave him one light jacket and one pair of winter shoes. His wedding ring and cross were not given back.

Two POWs were brought back from Taganrog, and several dozen others from other prisons. Most of them thought they were being taken to another prison. But Yuzhnyi realised that he was going home because the POWs were not beaten or tortured on the journey, and that only happens at prisoner swaps.

While she was waiting for her husband, Sevinj made his dream come true by opening a cafe called Charlie Chaplia in Lviv.The cafe logo features a heron ("chaplia" in Ukrainian) with a moustache like Mykhailo's

While she was waiting for her husband, Sevinj made his dream come true by opening a cafe called Charlie Chaplia in Lviv.The cafe logo features a heron ("chaplia" in Ukrainian) with a moustache like Mykhailo's

On the train, Yuzhnyi made another unexpected discovery.

"Jafar the border guard, Arn, an Azov soldier, and Misha, who's a police officer, were travelling with me on the special Rostov-Voronezh train," Yuzhnyi recalls. "They were sitting in different places, but I noticed that they all had the same shoes on - the same blue sneakers that our guards and balandyors used to wear. I asked the guys where they got those shoes from and they said: 'The Red Cross gave them to us.' Then I realised that those sneakers were supposed to be for us [POWs]. The Russians had just helped themselves to everything.

All we got from the Red Cross was one Mariia cookie and two or three sweets."

Yuzhnyi has already started going to his favourite football team's matches

Yuzhnyi has already started going to his favourite football team's matches

Mykhailo was brought back exactly two weeks before his 37th birthday. His wife Sevinj - they've been together for 10 years - was waiting for him at home. He'd thought about her constantly in captivity, and when he saw her again at last, it was as if they'd never been apart.

"I immediately started asking which of my relatives was still alive and how things were in Kharkiv. My grandma had died. I'd intended to go home before the full-scale invasion, but I didn't make it...

For the first five days after I got out, my eyes were red from the light because I hadn't seen the sun in two years. But it's an incredible thrill when you feel the wind stroking your cheek. This is freedom," the soldier recalls fondly.

But the biggest surprise for Yuzhnyi was the Charlie Chaplia cafe - a long-cherished dream of his that his wife made come true as she waited for him to come home from captivity. The cafe's logo is a heron ("chaplia" in Ukrainian) with a moustache like Yuzhnyi's, and those delicious burgers that he craved so badly are on the menu. Yuzhnyi is now undergoing long-term rehabilitation.

He plans to open several Charlie Chaplia cafes in other cities, to continue his military service, and to help other soldiers who return from Russian torture chambers. "The deep metaphysics of captivity can only be described by those who were there. We found ourselves in this absurd world through the looking-glass, and we stayed there for years.

But now I thank God that I went through that, because I went down to the very depths and I pushed off and up. I did not disgrace the honour of an Azov soldier, an officer, a Ukrainian, a Slobozhanets [someone from Sloboda Ukraine]. And I think I came out of there the winner."

Mykhailo Chaplia Olena Barsukova, Ukrainska Pravda. Zhyttia

Translation: Yelyzaveta Khodatska, Yuliia Kravchenko and Anna Kybukevych

Editing: Teresa Pearce