Human shield: how the Russians used civilians to protect their headquarters in Bucha

A young man, barely 23, is sitting on a bench. He's wearing black trousers and a black fleece, and the colour seems to sharpen the already angular features of his face. He has a patchy beard and short black hair stubbornly sticking up at the crown.

Most of his time he stares at the floor, hardly uttering a word except for the occasional "da" (yes) or "nyet" (no). This is Nikolai Kartashev, a Russian soldier. Initially a conscript, then a contract serviceman.

An occupier. A gunner who operated a Nona-S self-propelled artillery system in the 1st self-propelled artillery battery of the 234th Regiment of the 76th Pskov Guards Air Assault Division. Now he is standing trial in Irpin, Kyiv Oblast, for the murder of a Ukrainian civilian during the occupation of Bucha.

Those in black are the enemy

The majority of trials for Russian war crimes are conducted in absentia - without the accused present.

Kartashev's case is an anomaly. He is one of the few Russian soldiers who have found themselves on the defendant's bench, a man who can be seen and judged in person.

Advertisement:Fewer than 10 such trials have taken place in the three years of full-scale war. As of March 2025, you might recall one in Zaporizhzhia, where a Russian soldier stands accused of executing Ukrainian servicemen, or another in Irpin, where another Russian is on trial for torturing civilians.

If Kartashev and independent Russian media outlets are to be believed, his story unfolds like a grim, absurd tale. A native of Gukovo, in Russia's Rostov Oblast, he left school at 14 or 15. He was drafted into the Russian army in the spring of 2021 and signed a contract in August.

In January 2022, he was sent for training in Belarus. And on the night of 23-24 February, he crossed the border into Ukraine as part of the Russian force.

Russian soldier Nikolai Kartashev in court on 17 March 2025. He is accused of murdering an unarmed civilian.Photo: Stas Kozliuk

Russian soldier Nikolai Kartashev in court on 17 March 2025. He is accused of murdering an unarmed civilian.Photo: Stas Kozliuk

After the horrors of Bucha, Kartashev claims he tried to "withdraw from participation in the special military operation [as the Russians call the war in Ukraine]".

Instead, he found himself in the occupied part of Luhansk. He says he fled the combat zone in July 2022 and made his way home. In November or December of the same year, he was tried for desertion, receiving a lenient sentence - a year's probation.

In return, he was compelled to continue serving in the military under contract.

Advertisement:Around late January or early February 2023, Kartashev was captured near the city of Kreminna in the Serebrianka forest. But unlike many prisoners of war, he was never placed on a prisoner swap list. The reason soon became apparent: he had been involved in war crimes in Bucha.

Investigators from the Ukrainian National Police have established that convoys of the 76th Guards Air Assault Division attempted to enter Bucha on 27 February 2022. On that fateful day, Kartashev and his fellow soldiers, Dmitry Antonnikov, Ruslan Gorshkov, Denis Monakhov and Artyom Derkach, were in an armoured vehicle advancing along Vokzalna Street towards the junction with Novyi Highway, where the Novus supermarket was. An order from Vadim Tsvetkov, their commander, came through on the radio: anyone wearing black was the enemy.

"Those in black are the enemy," Kartashev would later testify during investigative reenactments in Bucha in 2023. The Russians spotted Valerii Koltunov, an unarmed shop security guard, and opened fire on him. According to Kartashev, visibility was clear and they shot at the civilian in single rounds.

Valerii was hit in the torso but managed to reach the entrance to the shop's back rooms and slip inside. He tried to call for an ambulance from there, but he died of his injuries before help could arrive. Shortly afterwards, the Russian unit came under fire from Pion self-propelled large-calibre guns belonging to Ukraine's 43rd Artillery Brigade and was forced to retreat.

Remnants of a convoy of the 104th Regiment of the 76th Pskov Guards Airborne Assault Division in Vokzalna Street, Bucha, 4 April 2022.Photo: Stas Kozliuk

Remnants of a convoy of the 104th Regiment of the 76th Pskov Guards Airborne Assault Division in Vokzalna Street, Bucha, 4 April 2022.Photo: Stas Kozliuk

Remnants of Russian military uniforms on Vokzalna Street in Bucha, 4 April 2022.Photo: Stas Kozliuk

Remnants of Russian military uniforms on Vokzalna Street in Bucha, 4 April 2022.Photo: Stas Kozliuk

A few days later, they made another attempt to gain a foothold in the city.

A bomb shelter for Russians

The 104th Regiment of the 76th Division of the Russian army was hit hard by the Ukrainian Pion systems.

After that, they retreated to the village of Zabuchchia, entering Bucha for the second time on 3 March. This time they tried to enter the city from the side of the neighbouring village of Vorzel. Ihor Bartkiv, head of the archives department at Bucha City Council, says the first Russians entered the city at around 11:00.

Kartashev's regiment, the 234th, advanced along Yablunska Street in the Sklozavodskyi neighbourhood. It was here, on the premises of a manufacturing company called Ahrobudpostach, that the Russians set up camp. They put their equipment, including Nona-S systems, next to the main building.

Around a hundred Bucha residents were sheltering in the basement of that building at the time.

The main building of Ahrobudpostach, where the Russian soldiers set up their headquarters and held 90 local residents in the basement, 24 January 2025.Photo: Stas Kozliuk

The main building of Ahrobudpostach, where the Russian soldiers set up their headquarters and held 90 local residents in the basement, 24 January 2025.Photo: Stas Kozliuk

Tetiana, one of the women who was hiding at 144 Yablunska Street three years ago, leads us to the bomb shelter. We exit from a dim corridor onto brightly lit stairs and go down into the basement. We see two large metal doors separated by a small corridor.

Made of thick metal, painted grey, with a vent lock that must be turned to lock them, the doors appear to have come straight out of school posters about civil defence, warning of the threats of nuclear war. Next, a long dark corridor and a large room with a table in the middle. Nearby is an entrance to a similar but smaller room.

The ceiling lights are on, but they aren't powerful enough to chase away the shadows from the corners. This is where the civilians lived for more than a week until the Russians allowed them to go home.

Advertisement:"There were about 90-95 people here altogether, including around 30 children. The youngest was a month old," Tetiana recalls.

Tetiana worked in the kitchen at a local cafe. They'd had an order for a large banquet just before the full-scale invasion started, so they had some supplies for the shelter. However, there were so many people that the food ran out in three days and the locals had to dash home to get more.

Tetiana would go to the kitchen to cook in the dark, not turning on the lights. The locals didn't know who might be in the vicinity, and they tried to avoid drawing attention to themselves. Breakfast was served at around 08:30 in the shelter: people would gather in the cafe in the building on quiet days, but during heavy attacks, food was brought down to the basement.

"We lived like this for eight days," Tetiana recalls. "Then one day I got a phone call: 'Auntie Tania, go to the shelter, quick! There's a horde [of Russians] heading towards you!' We went downstairs and locked ourselves in. The Russians opened the first door somehow, using keys from a tank.

But they couldn't open the second one, because our men wedged the lock mechanism with sticks and kept it shut. I started shouting not to take us. By then, we had no electricity and no ventilation.

People were afraid that the Russians were going to come in and shoot everyone. In the end, we decided to negotiate." Waiting behind the door was a Russian soldier with an assault rifle.

He took the negotiators to his commander, who forbade the civilians to leave the basement. The only exceptions were those who were cooking in the kitchen or taking out the waste bucket, since the sewage system in the shelter wasn't working and the Russians wouldn't let them use the toilets upstairs. There was no electricity, so some of the men took turns turning the ventilation handle to try and circulate the stale air.

The main room in the shelter at 144 Yablunska Street in Bucha, where the Russians held 90 local residents for several days, 24 January 2025.Photo: Stas Kozliuk

The main room in the shelter at 144 Yablunska Street in Bucha, where the Russians held 90 local residents for several days, 24 January 2025.Photo: Stas Kozliuk

Beds were made for the children out of wooden display boards about chemical and radiation protection that had been hanging on the walls.

The children's "bedding" consisted of the adults' coats. The youngest child cried almost continuously despite the parents' efforts to calm them down. Still, none of the people there complained about this.

The adults sat on the chairs against the walls most of the time. "The Russians promised they'd let us go. I kept asking them when.

And they kept saying 'Tomorrow morning.' We waited for five days. On the fourth day, I was allowed to go to the kitchen to heat some water for the little children," Tetiana shares. She went into the corridor with two other women.

There she saw several dozen wounded Russian soldiers on the floor. There wasn't much space, so the shelter residents had to step over the soldiers. Three guards with rifles followed them.

In the kitchen they struck up a conversation: they asked whether Ukrainians were happy with President Zelenskyy and tried to convince them that the Russian flag would soon be flying over the Verkhovna Rada (the Ukrainian Parliament). "What are you supposed to say to that? What would you say to a man with a gun?" Tetiana asks.

Advertisement:The people hiding in the basement couldn't see the Russians, but they could hear them clearly.

There were constant explosions around the Ahrobudpostach building, but some were different - louder and more powerful. Tetiana recalls that they would make the shelter tremble and shake. She doesn't rule out that this might have been Russian artillery firing.

Kartashev admitted in an interview with Slidstvo.info that their Nona-S artillery systems were shelling Irpin the whole time they were in Bucha. One system could fire up to 70 rounds a day.

The entrance to the shelter at 144 Yablunska Street in Bucha, where the Russians held 90 local residents for several days, 24 January 2025.

Photo: Stas KozliukThe Russians would come down to the shelter two or three times a day to check on the people there. One of them boasted that he was from Ukraine's Sumy Oblast and recited Taras Shevchenko's poem Zapovit (Testament).

Sometimes they brought rations and drinking water with them. Tetiana recalls that there was a woman in the basement who had lost loved ones because of the Russians. Her husband was the first: he had gone to look for her in the city, but some Russians had stopped him and shot him.

Her stepfather had been hiding in a basement near the Yablunka (Apple Tree) kindergarten. The Russians had ordered him to collect all the locals' phones and take them outside. As soon as he handed over the phones to the Russians, they shot him.

Tetiana says this quietly and calmly, almost as if it was something mundane. But now and then, she falls silent. She pauses for a long time, then changes the subject.

The people were released on 7 March. The shelter residents organised themselves: the parents with the youngest children left first, then those with older children, then the young people. Tetiana had time to grab her things from the kitchen, and through the window, she could see the Russian soldiers.

Young men, their faces uncovered, most of them looking about 20-22, were repairing their military vehicles. As she left the building, Tetiana saw a body to her right on the stairs. And there was Russian military equipment everywhere: outside the building, in the street, in the courtyards of nearby buildings.

And so, in complete silence, the people fled towards their homes, passing the Russians.

The kindergarten HQ

The National Police investigators have established, citing information from Ihor Bartkiv, that the Russians appeared near the Yablunka kindergarten on Tsentralna Street on 4 March, a day later than at Ahrobudpostach. They took up residence in the kindergarten, where around 350 people were hiding at that time, and in the surrounding buildings as well. The high-rise buildings and the nearby civilians provided the Russians with excellent protection from fire.

The 234th Regiment set up one of their headquarters in a high-rise building at 33 Tsentralna Street. Russian soldiers took over the homes of civilians who were either hiding in the basements of their buildings or had moved to the basement of the Yablunka kindergarten. Kartashev lived in one of the apartments.

Local residents who witnessed investigative reenactments with the Russian soldier in 2023 remember him telling the police that he had even tried to clean the floors after himself. Iryna Sylchenko, the head of the kindergarten, says people started arriving at the Yablunka basement after the first explosions on 24 February. "There were 355 people here in total, including 90 children.

They were different ages: there were older ones and some very young ones. We carried beds and blankets from the kindergarten to the basement. I remember a lot of people arrived after a convoy of Russians was shot at on Vokzalna Street.

The explosions were almost constant, so we didn't go outside much. We had food, the kitchen was working and bread was delivered until 4 March. After that it stopped," Iryna recalls.

Advertisement:She remembers that on 4 March, the residents of the bomb shelter heard rumbling: the Russians had arrived.

They entered the grounds in armoured vehicles, breaking through the fence. They parked the vehicles along the walls of the kindergarten and in a courtyard nearby. They went down to the entrance of the shelter and started knocking on the door, demanding that the people come out.

They asked who was in the basement. "We told them that we had children, pensioners, cats, dogs, even mice, but no weapons," Iryna continues. As we talk, children are arriving at the kindergarten - their chatter can be heard in the corridor.

The Russians eventually opened the shelter. They checked the locals and then walked around the kindergarten. They boarded up some of the entrances and put a sign on the door on the way to the shelter: "No entry.

Children." At first people were not allowed to go outside. On 6 March, the water and electricity were cut off.

People started asking to go outside where there were toilets and open spaces where you could cook. No one was allowed to leave the kindergarten grounds, so the residents were unaware of what was happening in the courtyards of the neighbouring buildings.

Local residents who hid in the basement of the Yablunka kindergarten during the occupation of Bucha. The exact date of the photo is unknown.Photo: Kindergarten employees

Local residents who hid in the basement of the Yablunka kindergarten during the occupation of Bucha. The exact date of the photo is unknown.Photo: Kindergarten employees

Tetiana met us some 200 metres from the kindergarten in the courtyards of some high-rise buildings.

She and her family had hidden in the basement of their building since the start of the invasion. Tetiana says they knew the kindergarten had a basement, but she and her family had decided to stay closer to their apartment. "There were rumours that the Russians were somewhere nearby.

But they came here on, I think, 4 March [2022]. They settled down in the kindergarten and in our homes. They glanced into our basement, but we said there were only women and pensioners there, and they didn't even come in.

Actually we did have a few men. A little later, they let us go out and go back to our apartments," Tetiana recalls. This probably happened some time between 7 and 10 March.

Tetiana recalls that there were Russian military vehicles and soldiers in the courtyard, and also Russian troops on the roofs. When the people came out of the basement, they were ordered to walk only through the middle of the courtyard, looking only at their feet. At around this time, there were rumours about a "green corridor" through which people could evacuate.

"While the Russians were here, my son managed to let our military know there were civilians in the buildings around," Tetiana says. "I spent the entire occupation here. And imagine: we could hear attacks and explosions all around us, but not a single shell flew into the kindergarten or into our courtyard! Some people used the [green] corridor to evacuate to Irpin and then to Bilohorodka on 10 March."

Iryna, the head of the kindergarten, says the same thing: on 7 March the Russian military summoned her and told her the Ukrainians had agreed to a "green" evacuation corridor. However, the Russians were not too happy about the civilians leaving. They tried to persuade the civilians that they would be safer in the basement.

They said, "We don't know what's going to happen next or who controls the territory."

Children hiding from shelling in the basement of the Yablunka kindergarten during the occupation, March 2022. Photo: Kindergarten employees

Children hiding from shelling in the basement of the Yablunka kindergarten during the occupation, March 2022. Photo: Kindergarten employees

But about 50 people left on 7 March and about the same number the following day. In general it was people with children who left. Iryna recalls that by 10 March most of the people still in the kindergarten were pensioners, and she too decided to leave the city.

On that day, one of the Russian soldiers told her, "Come with us." As they walked to the centre of Bucha, people saw burnt-out buildings and dead bodies lying on the ground. They eventually left the occupation on evacuation buses via Vorzel.

"I remember we were driving along, and people were running to the buses in Vorzel, shouting 'Take us with you!'" Iryna says. "As soon as we reached the Zhytomyr highway, we came under fire. The driver turned around and we drove through some villages to Bilohorodka. I still remember the sights that met my eyes: a burnt-out car, a man in a terracotta-coloured jacket lying there.

Fortunately, we hadn't had seen any killing or torture in the kindergarten basement. We heard that some bodies were found somewhere near the kindergarten. And once we saw a civilian man who the Russians captured.

People say he's dead now." Iryna also recalls that the Ukrainian soldiers were aware that there were a lot of civilians in the basements: some of the people who were in touch with Ukrainian soldiers had let them know. Our conversation is interrupted by an air-raid warning: one of the Russian drones launched that night had turned around in Zhytomyr Oblast and returned to Kyiv Oblast.

The air-raid siren is still going as the corridor fills with children being led to the shelter by their teachers. These little kids seem to have the eyes of adults. Within minutes, everyone is in the shelter.

Advertisement:A police officer who goes by the alias "Beard" confirmed what the civilians said.

Beard is now fighting in one of the consolidated police units. Three years ago, Beard worked as an aerial reconnaissance man, including in the area around Yablunska Street in Bucha. He says they saw the Russian paratroopers, knew they had positions there and recorded their coordinates.

"We used Mavic drones, and the video was recorded on flash drives," the police officer recalls. "Unfortunately we lost some of the video because we lost the drones. But yes, we saw Russian paratroopers in the area of Yablunska Street. We saw civilian corpses on that street in mid-March.

There was a lot of Russian equipment, mostly infantry fighting vehicles (BMDs). There were probably Nonas among them, because they're a similar design and height." As for the Yablunka kindergarten, Beard saw about 10 BMDs in the courtyards of the high-rise buildings.

And next to the BMDs were - civilians; they would come out of the buildings in groups of four to six people to cook food on an open fire. There were Russian soldiers nearby. "Ten pieces of equipment in one place is a good, easy target.

And of course we passed on the data to the artillery troops. And of course we reported that there were civilians nearby. The artillery troops we passed the coordinates to said they wouldn't attack the target, specifically because there were civilians there.

Of course the Russians knew there were civilians in the courtyards and basements and knew they were living there. I think we can safely say they were hiding behind them," the policeman says.

Stolen washing machines

The law enforcement officers found out that on 10 or 11 March, at least some of the soldiers in Nikolai Kartashev's regiment left Tsentralna Street and moved on to the Continent residential complex in Oleksa Tykhoho Street. It was then, on Tsentralna Street, that the worst atrocities began, because the Russian soldiers were replaced by others.

The locals recall that they were older and dirtier. Tetiana and her husband Vasylii were taken to one of the apartments to be interrogated because they had helped to build fortifications in Irpin. "My Vaska (Vasylii) told me not to cry out, not to show them that it hurt, because they enjoy that.

I remember three of them: one was Belarusian, one was from somewhere in Chechnya, and one was Russian. They 'talked' with me. They killed my husband, Vasia.

I was basically their prisoner afterwards. I refused to eat, I was afraid the food would be poisoned. I only drank tea with sugar," Tetiana remembers.

She recalls several cases of people who were taken away for "chats" and never returned. After the city was liberated, Ukrainian soldiers and journalists found the bodies of some locals around the kindergarten. Russian troops shot civilians outside a school not far from Tsentralna Street.

The Russians set up another headquarters at the Continent residential complex and installed artillery along the perimeter for attacks on Irpin. Ihor Bartkiv says the 234th Regiment remained in the city until the end of March, until the Russians began to retreat. However, local residents report that there were several Russian rotations at the Continent residential complex, but they do not know which units they were.

Andrii Strakhovskyi, director of the property development company that built the housing complex, was not in the city during the occupation, but he has collected information from local residents. He recalls that the Russians kept people who hadn't managed to evacuate in one of the basements. And as in the other cases, no one was allowed to go outside.

Strakhovskyi says the Russians set up firing positions around the Continent's perimeter. Rotations were held once every 5-7 days. The 76th Division was replaced by Russians who looked like Buryats.

"They broke into every one of the 600 apartments in the complex," he says. "The looting began shortly before the end of March. The videos from Bucha that you may have seen with washing machines on tanks - those are from Continent. They lived in these apartments."

Nikolai Kartashev lived there too, on the third floor. During an investigative reenactment, he even went into the apartment and met the owner. Strakhovskyi recalls that the reenactment drew many locals, some of whom wanted to see Kartashev and others to beat him up.

Yurii, a resident of the Continent housing complex, tries to clean up in the courtyard after the Russian occupation, 4 April 2022.Photo: Stas Kozliuk

Yurii, a resident of the Continent housing complex, tries to clean up in the courtyard after the Russian occupation, 4 April 2022.Photo: Stas Kozliuk

When the Russians fled, they left total devastation behind them: the brand-new housing complex did not seem to have a single window left, there were burnt-out cars everywhere, and in the middle of the courtyard, the Russians had made a model of an artillery system out of a jeep and some wooden boxes.

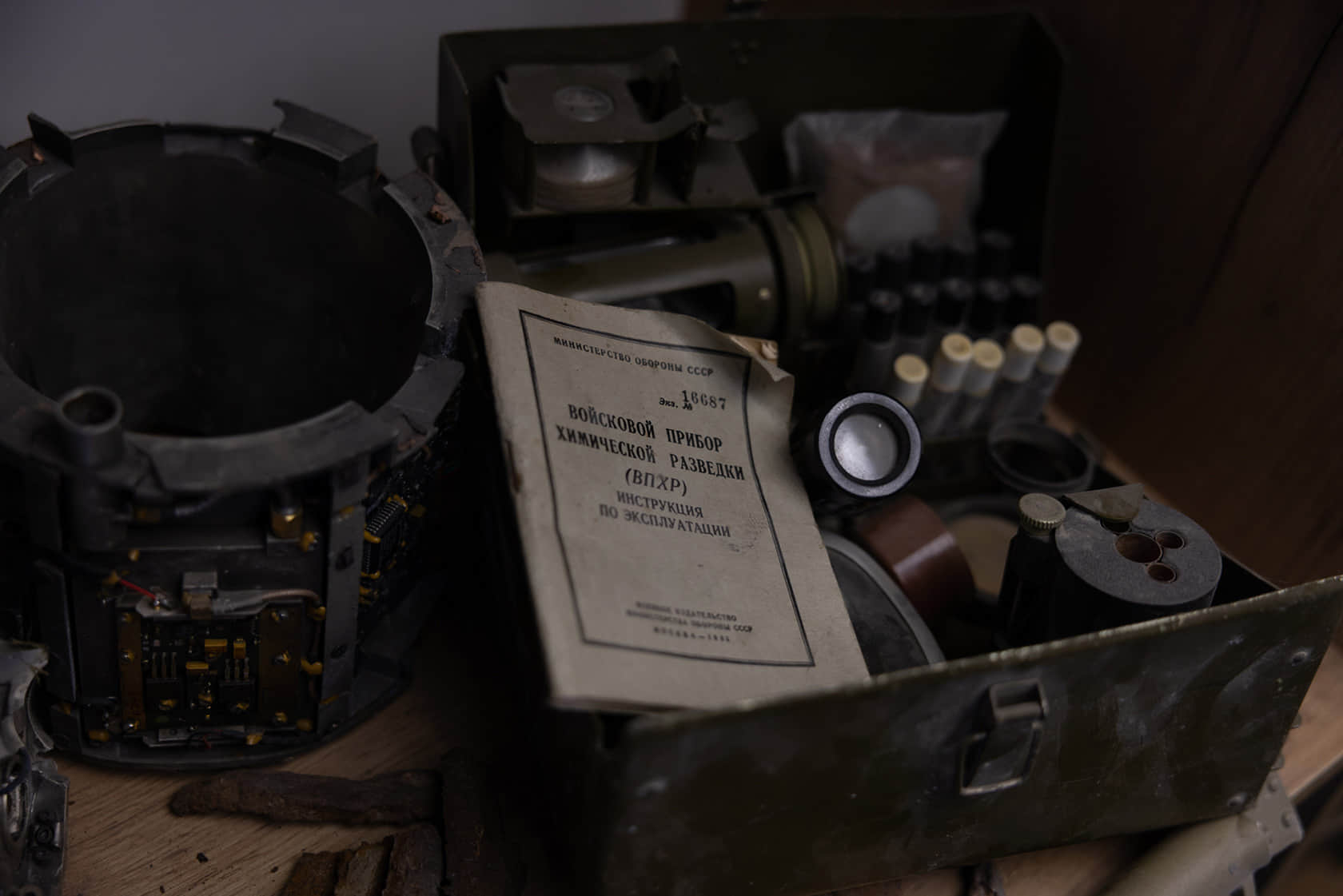

Local residents collected all the "artefacts", hoping to open a museum, which is still under development. All the items are kept in one room. Andrii shows us everything that has been preserved: parts of tanks, projectile boxes, plastic bags that held rations, and even chemical reconnaissance devices dating back to the 1960s.

Artefacts collected by residents of the Continent housing complex in Bucha after liberation, 11 March 2025.Photo: Stas Kozliuk

Artefacts collected by residents of the Continent housing complex in Bucha after liberation, 11 March 2025.Photo: Stas Kozliuk

A Soviet-era chemical reconnaissance device found by residents of the Continent housing complex after the retreat of Russian troops from Bucha, 11 March 2025.Photo: Stas Kozliuk

A Soviet-era chemical reconnaissance device found by residents of the Continent housing complex after the retreat of Russian troops from Bucha, 11 March 2025.Photo: Stas Kozliuk

It is difficult to say exactly how many people were held in the basement at the Continent.

Andrii Strakhovskyi says it may be several dozen. And none of them want to talk to journalists and recall the traumatic events that happened three years ago. The Bucha City Council archive department does not have an exact number of the civilians the Russians used as a shield.

"This is a huge housing complex," Bartkiv says. "Some people were there for a few days and evacuated, some left later, and some stayed. But the Russians did the same things there as they did in other places: they robbed, tortured and killed. In general, one shouldn't look for logic in their actions: the youngest victim in our hromada was 19 months old, and the oldest was 100. [A hromada is an administrative unit designating a village, several villages, or a town along with their adjacent territories - ed.] Because of the Russians, people died not only of gunshot wounds but also from lack of help.

Some died of blood loss, others had heart problems and couldn't get help." Bartkiv is convinced that the occupation of Bucha is one of the most carefully recorded Russian war crimes, since the video from surveillance cameras has been preserved. The Russians were also photographed and filmed by the locals, who didn't always understand the risks.

Some Russians also lost their documents during the retreat, and these contain the names of their personnel. Ihor Bartkiv is collecting all available information and organising it into an archive, which he shares with the police.

A resident of Bucha killed by the Russian military at the Continent housing complex, 4 April 2022.Photo: Stas Kozliuk

A resident of Bucha killed by the Russian military at the Continent housing complex, 4 April 2022.Photo: Stas Kozliuk

As of March 2025, together with the National Police, it has been possible to identify over a thousand Russians involved in crimes against civilians. Sometimes it is possible to establish not only the locations of Russian headquarters, but also the Russian soldiers who killed people.

This is how journalists from The New York Times found the Russians who killed the fighters of the Territorial Defence Forces on Yablunska Street.

Closed court

Even more could be learned from court hearings, especially those where Russian soldiers are being tried. However, the Ukrainian judicial system has its own problems, such as the lack of judges or the time or inclination to hear cases. For example, in January 2025 the Irpin city court, which is dealing with Kartashev's case, started the proceedings from scratch because the panel of judges had changed.

There had already been a change of defence lawyer for the accused Russian - he is now represented by Mykola Motruk, a lawyer from a free legal aid centre.

Nikolai Kartashev, a Russian soldier accused of murdering an unarmed civilian, in court, 17 March 2025.Photo: Stas Kozliuk

Nikolai Kartashev, a Russian soldier accused of murdering an unarmed civilian, in court, 17 March 2025.Photo: Stas Kozliuk

The next session was held a mere two months later, on 17 March - all the previous ones had been postponed for one reason or another. During that session, the court went into closed mode at the request of Kartashev's lawyer, referring to the Geneva Conventions. Now, neither journalists nor residents of Bucha and Irpin are permitted to attend.

This was allegedly due to the publication of the names of the accused and his lawyer. In its ruling, the court referred to the fact that Kartashev had been threatened. During a break in the hearing, we tried to clarify with the Russian whether there really was any risk.

The accused replied that he "just doesn't want to be shown". We asked Mykola Motruk, Kartashev's lawyer, a similar question during the break, but he refused to comment. Although there is no case law in Ukraine, certain court judgments can become acceptable practice.

Whether court hearings concerning Russian occupiers should be closed to the people who suffered from those Russians' actions is a debatable issue - because it raises the question of whether the right of a Russian prisoner of war accused of a war crime ranks higher than society's right to see a fair trial. Reference: According to Bucha City Council's archives department, as of March 2025, 581 residents of the Bucha hromada have been identified. Another 48 people were not identified and were buried in the cemetery with numbered plates, and 37 people from the Bucha hromada are still missing.

Another 34 are in Russian captivity. Author: Stas Kozliuk Editor: Yevhen Buderatskyi

Translation: Tetiana Buchkovska and Yuliia Kravchenko

Editing: Teresa Pearce