What's going on with the Russian economy?

The sanctions are working, but Russia has adapted to them. How is the Russian economy doing after 20 months of the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine? Ukraine's Western allies have imposed severe restrictions on Russia's economy since the beginning of the full-scale invasion.

Eleven sanctions packages covered the Russian banking system, industry, and even the energy sector. The restrictions concerned exporting dual-use goods to Russia that could be used for weapons production. International corporations began to leave the Russian market en masse.

Advertisement:Twenty months into the full-scale invasion, the partners' enthusiasm for introducing new sanctions packages has somewhat waned, and the restrictions that have already been imposed are gradually losing their effectiveness. Moreover, the Russian economy is showing signs of moderate recovery, which has enabled the Russian Ministry of Finance to allocate record war spending in the 2024 budget.

The Kyiv School of Economics (KSE) has recently released a report on the state of the aggressor country's economy as of October 2023. The report indicates that the Russians have adapted to life under sanctions and are managing to circumvent restrictions and even generate income amid high oil prices. What is happening in Russia's economy, and what new sanctions might hinder the Kremlin's ability to finance the war?

Sanctions against Russian oil

Restrictions on Russian oil took effect on 5 December 2022.

The G7 countries, in fact, capped the maximum price at which the "black gold" can be purchased from the Russians at US£60 per barrel. This move was expected to reduce the Kremlin's ability to finance the war rather than lead to an oil shortage in the global market. This mechanism was implemented through the mediation of Western insurers.

The fact is that tankers carry most of the oil that the Russians do not transport through pipelines. Furthermore, each tanker must have appropriate insurance, otherwise the vessel cannot enter ports. This is precisely why Ukraine's allies have banned companies from taking out insurance policies if the selling price of the oil they transport exceeds the established limit.

This restriction initially seemed quite effective as average Russian oil prices fell to US£50-52 per barrel. However, its price has been steadily above US£60 per barrel since July and exceeded US£80 in September.

Russia has managed to circumvent the measures by forming what is called a "shadow" fleet. The Russian Federation has, in fact, purchased or leased old tankers around the globe and used them to deliver its oil.

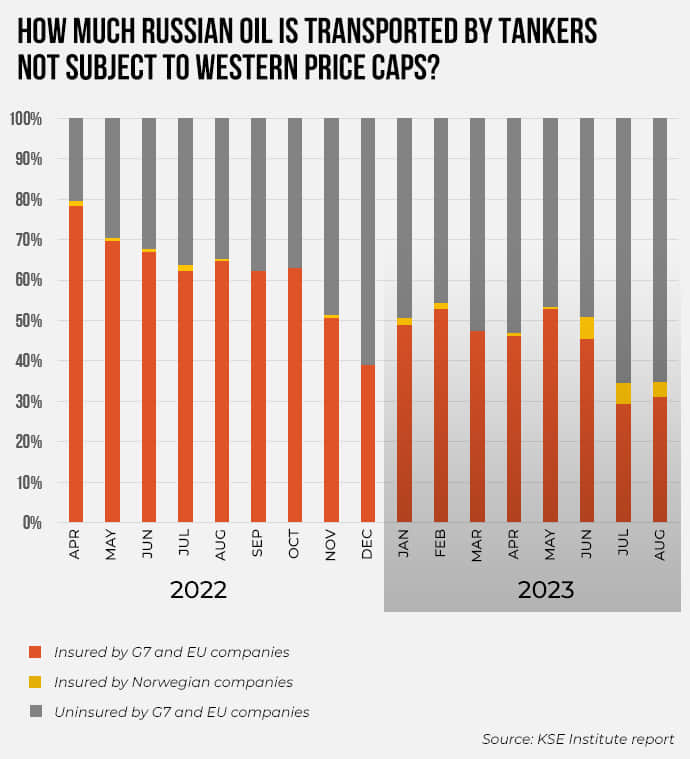

The crucial thing is that these tankers also have insurance policies, but not with Western companies. Therefore, the export price of such oil is not regulated by Western sanctions. As of August, tankers that were not insured by EU or G7 companies delivered a total of 65% of Russian oil transported by sea.

This compares to only 20% in April 2022.

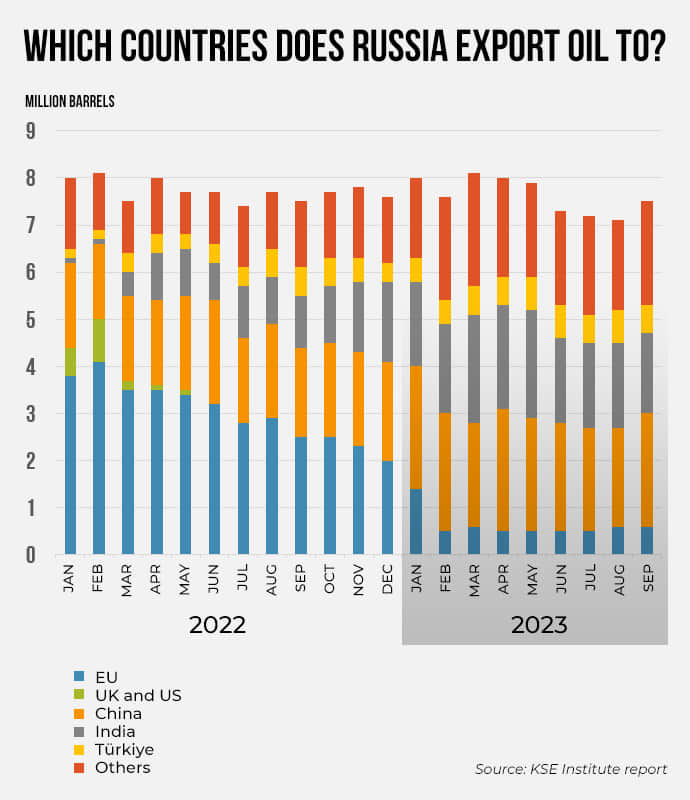

The Kremlin also managed to find an alternative to Western markets besides replacing Western tankers. The EU, the US, and the UK accounted for 55% of Russian oil consumption in early 2022. Raw materials have been transported mainly to China, India and Turkiye since the beginning of 2023.

Of course, this diversification of export destinations has its drawbacks.

Russia is not selling oil for US dollars but for less convertible currencies. India, for example, pays in rupees [US£1 = roughly INR 83]. Consequently, this leaves Russian oil exporters stuck with billions of rupees, which they can actually use only to acquire goods from India.

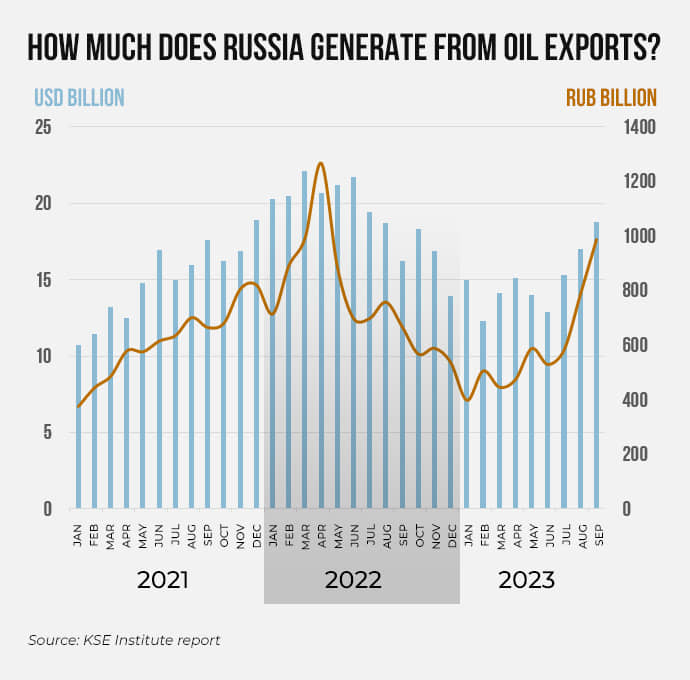

Nevertheless, Russian oil revenues have been steadily increasing over recent months. It's all thanks to the rise in global oil prices and Russia's expanding ability to circumvent price restrictions with the help of the "shadow fleet".

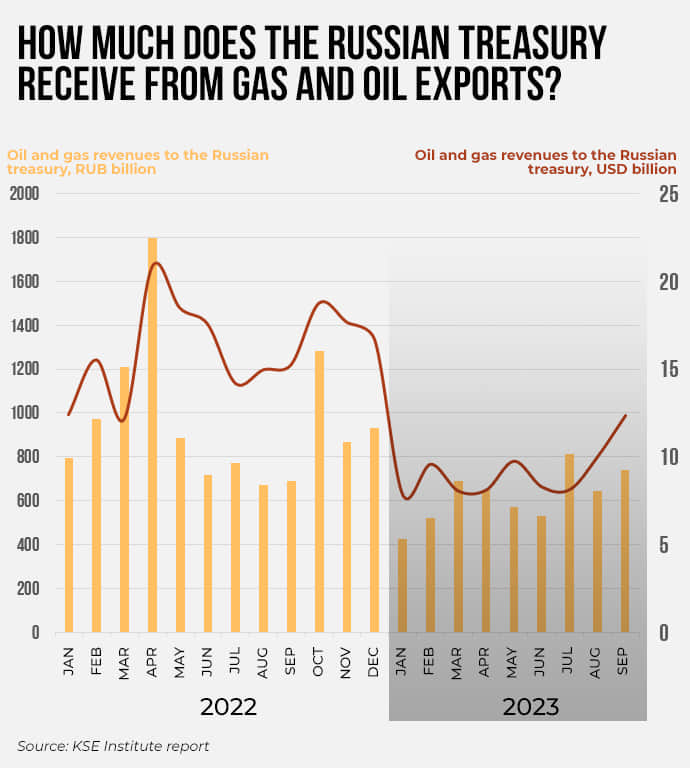

As export revenues grow, so do tax revenues to the Russian coffers. They reached RUB 1 trillion [US£ 10.6 billion] in September.

The state of the Russian budget

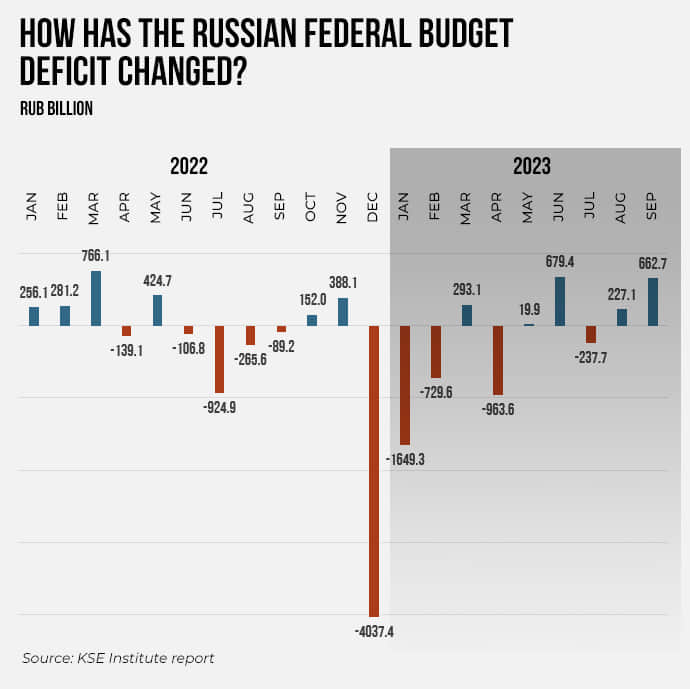

The year 2023 kicked off with good news for Ukrainians: the Russian federal budget deficit was growing faster than expected, reaching 80% of the annual forecast in three months.

However, the actual financial problems in Russia had started a little earlier. The Russian budget deficit exceeded RUB 4 trillion [US£42.5 billion] in December 2022. This happened in the first month of the oil export restrictions.

The record deficit forced the Russian government to seek additional sources of funding.

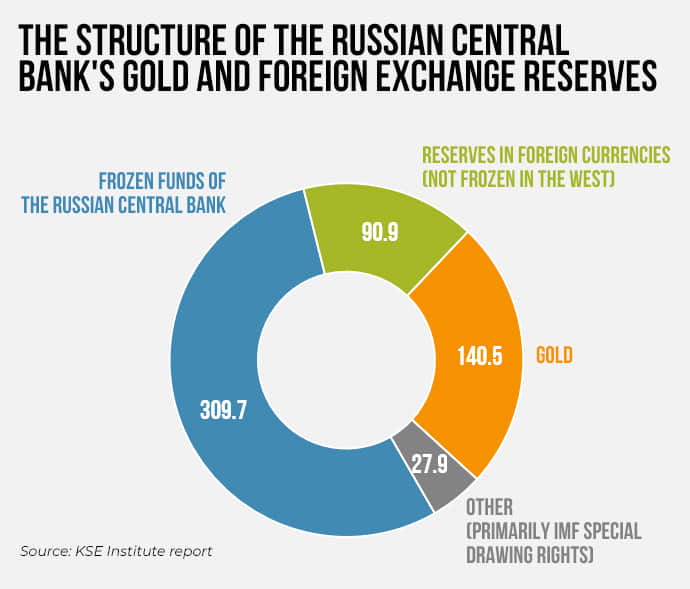

Regrettably, Russia still has significant financial reserves that can support its public finances. "We must admit that Russia was preparing for war not only militarily but also financially. For example, it has reduced its dependence on the dollar and euro in the structure of its gold and foreign exchange reserves.

Besides, it has accumulated about US£180 billion in the National Wealth Fund (NWF)," explains Yuliia Pavytska, co-author of the KSE report on the state of the Russian economy. The Russian government financed its expenditures directly from the NWF in December 2022, the most critical month for the Russian budget, by RUB 2.4 trillion [US£25.4 billion]. The remaining deficit was covered by domestic borrowing, mainly provided by local state-owned banks.

The Russian government also used funds from the NWF in 2023, but to a much lesser extent, covering expenditures worth RUB 560 billion [roughly US£5.6 billion] in January-September. Wasting the National Wealth Fund has had its effect. Although its size has remained virtually intact in RUB terms since the beginning of this year, it has fallen from US£182.6 billion to US£140 billion in foreign currency.

As impressive as US£140 billion is, the vast majority of the IWF's assets have low liquidity. The fund holds almost US£43 billion in relatively liquid assets, such as euros and Chinese Yuan [US£1 = roughly CNY 7.3]. A further US£30.6 billion is gold.

The rest are shares in the domestic majority state-owned Sberbank and other assets that take time to sell. Put another way, the Russian government is running out of options to quickly support the budget with this fund. The necessity to support the Russian federal budget with funds from the NWF fell in 2023 as the situation for the Kremlin began to improve.

The budget deficit was shrinking, and there was even a surplus in some months. Consequently, the annual deficit plan reached 58% in January-September, compared to 80% in the first quarter. The recovery in oil exports and the devaluation of the rouble facilitated this.

The latter was not a decisive factor behind the growth of Russian budget revenues. The higher level of global oil prices meant that Russia's oil and gas income also increased in dollar terms.

Stabilisation in public finances has paved the way for the Russian Finance Ministry to plan an increase in spending in the 2024 budget. The biggest addition is expected in defence, with spending on the war against Ukraine increasing by 68% - from this year's RUB 6.4 trillion [roughly US£68,08 billion] to RUB 10.8 trillion [roughly US£114,9 billion].

What about the rouble and finances?

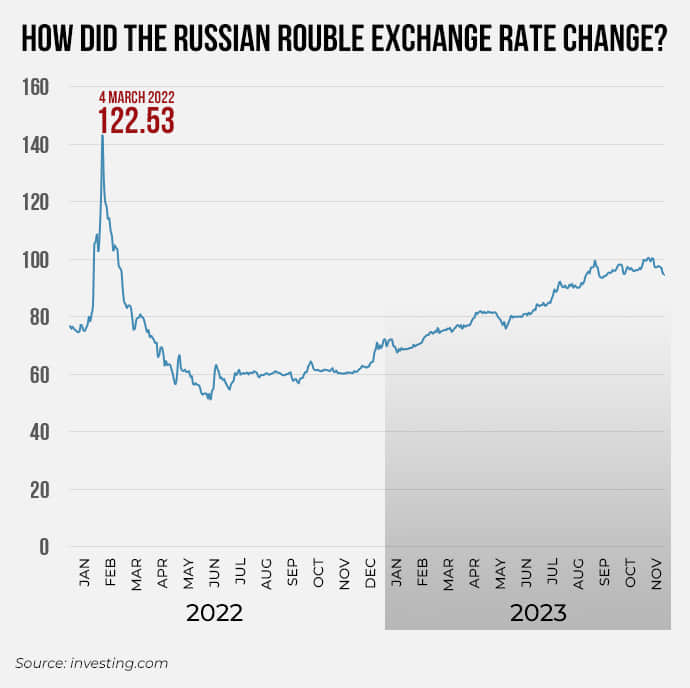

Western sanctions have not only drained Russia's sovereign wealth fund, but also led to the devaluation of the rouble.

Problems with foreign exchange earnings from oil sales and other restrictions resulted in the dollar's exchange rate in Russia rising to 100 roubles in the summer and has been fluctuating around this psychological mark for two months now.

The Central Bank of the Russian Federation has few options to support the rouble. The majority of its liquid reserves (approximately US£310 billion) are frozen in the EU, the UK and the US. The rest of the US£570 billion is mainly gold (US£141 billion).

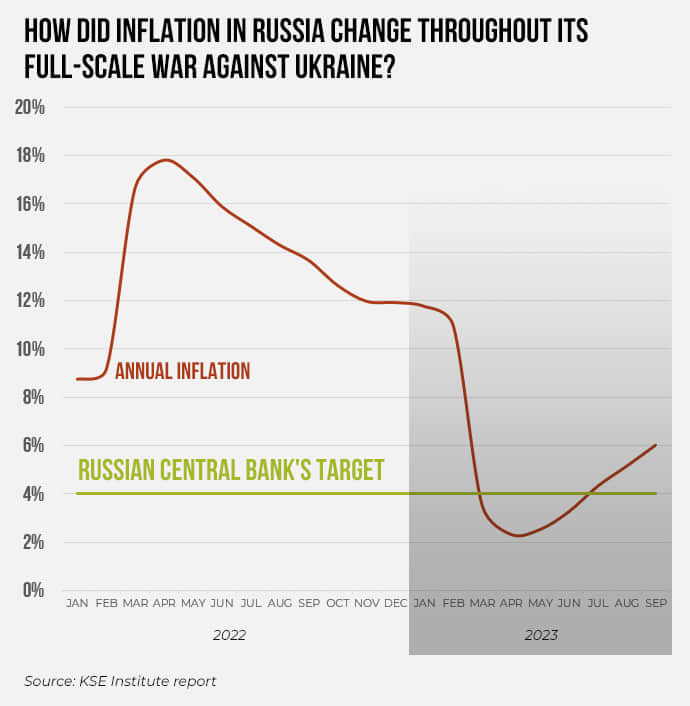

The devaluation of the rouble has hit Russians not only psychologically, but has already affected the rate of price growth.

At the beginning of the year, Russian statistics services reported that annual inflation had fallen below the Central Bank's target of 4%. However, this was primarily due to the high comparative base of 2022, when price growth rates reached 16-18%. Moreover, Rosstat's inflation data itself raises doubts about its reliability.

Over the course of the year, the service repeatedly changed the structure of the market basket on the basis of which it calculates the price growth rate.

The Russian Central Bank responded to the surge in inflation by gradually raising its key interest rate. Its size will ultimately affect the cost of lending and the cost of the Russian government's borrowing on the domestic market. This could slow down the economy's growth in the future.

How much will the Russian economy grow?

Western sanctions had a negative short-term impact on the Russian economy.

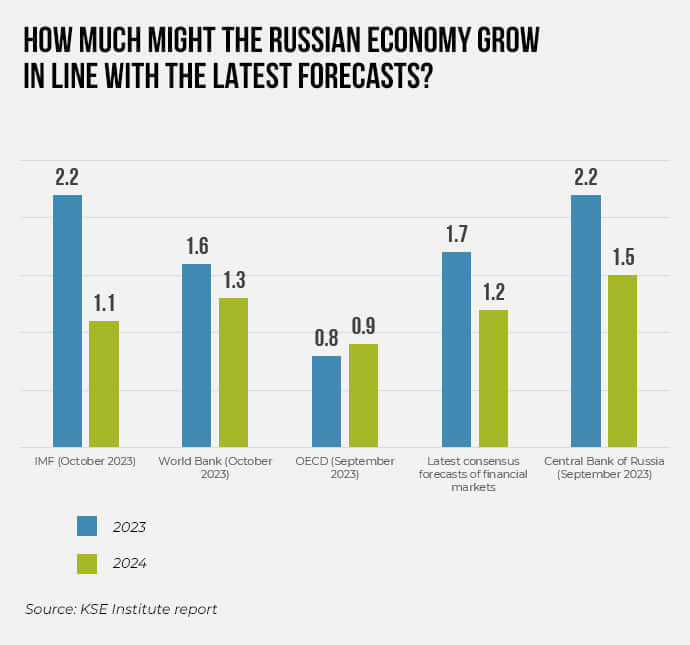

According to the World Bank, it fell by 2.1% in 2022. However, Russians are currently managing to adapt to living under international restrictions. The world's leading financial and economic organisations expect Russia's GDP to grow by 0.8-2.2% in 2023.

One of the biggest incentives working to restore the Russian economy is currently military procurement.

The funds that the Kremlin uses to equip the occupation army and produce missiles, ammunition and heavy equipment have helped to increase production in related industries. In addition, Russia's relatively high GDP growth rate is affected by the low comparison base of the previous year. This effect is expected to wear off in 2024, and the growth rate of the Russian economy will slow down slightly.

What needs to be done?

The Russian economy is showing signs of recovery from the sanctions.

This means that Putin's regime will be able to accumulate more resources to continue the war that led to the sanctions in the first place. Therefore, the West needs to work to impose new and tougher restrictions on Russia so that it can feel the cost of war. Special attention should be paid to the energy sector.

In particular, the price cap for Russian oil should be lowered. This will reduce the aggressor's budget revenues from the sale of the share of oil that is still exported by Western tankers. An additional sanctions step proposed by Kyiv School of Economics analysts is to impose restrictions on Russia's tanker purchases to limit its ability to replenish its "shadow fleet".

Unfortunately, the development of a "shadow fleet" of tankers has become an effective mechanism for Russia to circumvent energy sanctions. However, it is possible to try to extend sanctions to this fleet. To do so, Western countries should demand that Russian tankers have Western environmental risk insurance to pass through their territorial waters.

Most Russian oil and oil products are exported through ports on the Baltic and Black Seas. The way out of these seas is through rather narrow straits controlled by NATO countries. Moreover, these countries themselves have a vested interest in ensuring that shadow fleet tankers have high-quality insurance, as most of these vessels are old (over 15 years old) and the risk of an accident during oil transport is quite high.

Potentially, expanding the insurance requirements for Russian tankers could subject them to price controls and significantly limit Russia's revenues from the sale of oil and oil products. In addition to expanding restrictions on oil, the West may hit another component of Russia's energy exports - liquefied natural gas (LNG). KSE analysts say that Russia still exports US£8 billion worth of this fuel to the EU.

Ultimately, the aggressor uses these funds to wage war against Ukraine. Among the proposals already being discussed as part of the next sanctions package is a ban on the export of Russian diamonds. According to KSE's calculations, this is worth about US£4 billion a year.

Read also: How Western energy sanctions against Russia are failing

Among the financial sanctions, the most painful for Russia may be further isolation of its banking system from the global financial market by disconnecting more banks from the SWIFT system.

In addition, Ukraine continues to insist on putting Russia on the Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering (FATF) blacklist. Finally, the West should strengthen control over violations of existing anti-Russian sanctions. Violators should be held accountable for helping Russia circumvent restrictions.

It is also necessary to strengthen cooperation with third countries so that they do not become intermediaries for circumventing sanctions. By Yaroslav Vinokurov, Ekonomichna Pravda

Translation: Artem Yakymyshyn and Myroslava Zavadska

Editing: Susan McDonald