How Poland continues to import Russian agricultural products

As Ukrainian agricultural products are being blockaded at the border, Poland continues to pay hundreds of millions of dollars to Russian and Belarusian companies for seeds, oil and animal feed. The first thing readers should realise is that the EU has not suspended all agricultural trade with Russia, despite its full-scale war of aggression against Ukraine entering its year. The European Union continues to trade with a country that occasionally threatens to turn Warsaw and other European capitals into radioactive dust.

Ukraine's European partners purchase not only vital energy resources from Russia, but agricultural products, with exports of the latter from Russia to the EU totalling billions of dollars.

Advertisement:Talk of sanctions against Russian agricultural products has been taboo since the beginning of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Hardly any country in the pro-Ukraine coalition has even dared to introduce them, with only Latvia taking the first steps to call for such measures. Under the auspices of saving vulnerable countries from starvation, Russian and Belarusian agricultural and fertiliser products have been left untouched.

Russian food can still be exported without restrictions even to countries that have no shortage of other food, including Ukraine's neighbour Poland. Lorries with Polish licence plates freely travel to and from Belarus. Official statistics indicate that Poland paid hundreds of millions of dollars to Russian and Belarusian companies for seeds, oil, and animal feed in 2023.

In some cases, imports of these goods actually increased compared to before the war.

What quantity of agricultural products does Poland import from Russia and Belarus?

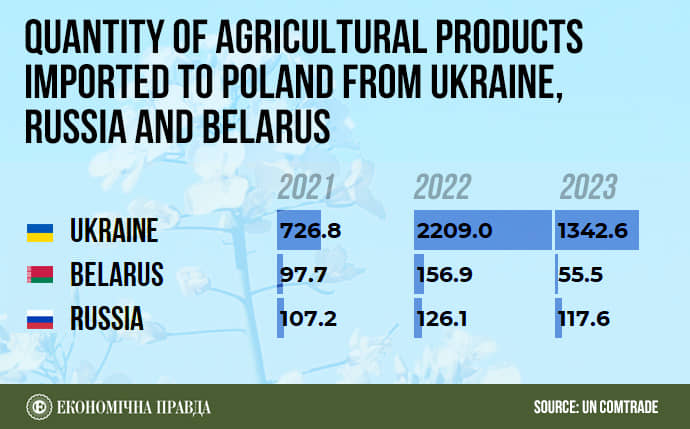

Ukrainian agricultural exports to Poland dropped by 40% last year, although the reduced volume is still significant, being valued at US£1.4 billion. There are two reasons for this decline: firstly, Ukraine is once again able to export goods via the sea, with shipping taking priority over overland trade. Secondly, Poland banned imports of Ukrainian wheat, maize, rapeseed and sunflower seeds in August amid protests; in September the list of proscribed commodities was expanded to include rapeseed cake and meal, corn bran, wheat flour and derivatives.

At present, the road route through Poland accounts for 5% of Ukrainian exports. Therefore, when the Poles resumed blocking Ukrainian road crossing points at the end of the year, it didn't lead to economic disaster, but it did affect certain exports: cables, dairy and meat products, semi-finished products, etc. On top of that, sowing crops is often delayed as farmers must wait weeks for their lorry shipments of seeds and machinery to make it through the blockade.

The protests at the border continue even though Poland has reiterated that the banned Ukrainian goods are only in transit, and not destined for the domestic market. About 6,000 vehicles are currently queuing to leave Ukraine for Poland, with 2,000 waiting to enter Ukraine. At the same time, freight traffic between Poland and Belarus continues uninterrupted through the only operating cargo checkpoint, Koroszczyn-Kozlovichi, near the city of Brest, Belarus.

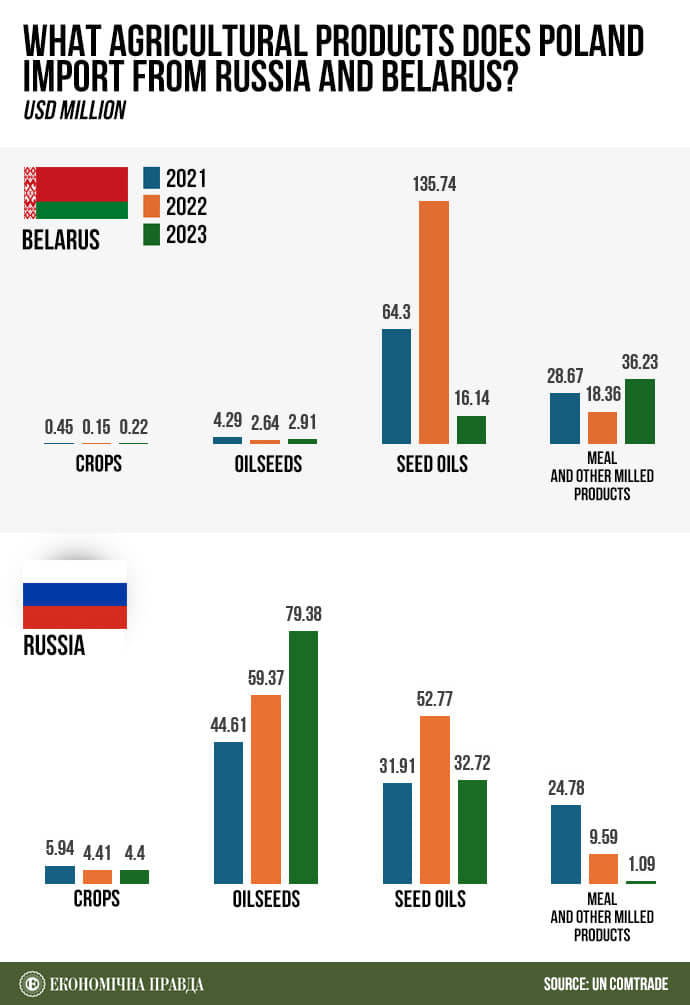

UN data revealed that Poland exported a total of US£3.7 billion worth of goods to Russia and US£2.8 billion to Belarus last year. On the other hand, Poland imported goods to the tune of US£450 million from Belarus and US£2.6 billion from Russia, 50% of which by quantity consisted of fuel imports. At the same time, if we focus on agricultural products alone, the value of their imports from Russia to Poland reached US£117 million, exceeding the pre-war 2021 figure.

Notably, imports of grains and oilseeds more than doubled, while imports of seed oil remained virtually unchanged. However, imports of meal and other milled products fell from US£25 million in 2021 to just US£1 million in 2023.

For reference: The volume of "agricultural products" is defined as the amount of trade in goods classified as HS 10 Cereals, HS 12 Oilseeds, HS 15 Seeds and HS 23 Milled products and meal (the HS numbers indicate which category a commodity falls into under the U.S. Harmonised Tariff Schedule).

Finished food products are not included.

It's a similar story when it comes to Poland and Belarus. Imports of grains, oilseeds, and meal gradually increased in 2022 and 2023. Poland bought a total of US£55 million in agricultural products from Belarus last year.

Notably, these goods included rapeseed meal (milled rapeseed used in livestock feed). Poland has banned the import of this product from Ukraine effective September 2023 under pressure from protesters, though it has continued to acquire it from neighbouring Belarus. Moreover, the volumes grew after the embargo was introduced as Poland purchased US£7.7 million worth of rapeseed meal from Belarus in October-December.

Therefore, Poland has not only continued to trade with Russia and Belarus, but also upped its imports of agricultural products, which are the cause of long-running economic disputes with Ukraine.

However, two facts must be understood to put these figures into context: Fact one: The volume of Poland's imports from Russia and Belarus is significantly lower than from Ukraine. Last year, Ukraine sold US£1.4 billion worth of agricultural products to Poland, while Russia and Belarus exported US£117 million and US£55 million, respectively.

Fact two: Apart from meal, imports of which from Ukraine have been embargoed, Poland scarcely imports any other Russian and Belarusian goods.

The only other item still traded is Russian sunflower seeds, though in meagre volumes of around £50,000 per month.

Just business under Polish number plates

The only checkpoint on the Polish-Belarusian border still open for freight traffic is Koroszczyn-Kozlovichi. Last spring, Polish hauliers protested here for the first time. Back then, they protested against Belarusian and Russian firms that were "taking the bread from their mouths" and registering shell companies in Poland to continue doing business in the EU after sanctions had been imposed.

At the same time, the EU has implemented carveouts for hauliers transporting agricultural products from Russia and Belarus in its sanctions regime. Ukrainska Pravda journalist Mykhailo Tkach, who spent several days at the border between Poland and Belarus and was detained by Polish secret services, has confirmed that most of the vehicles crossing the border into Poland had Polish number plates. After all, Russian and Belarusian goods travelling to Poland can be transported by road and rail, as the railway connection between Poland and Belarus remains operational.

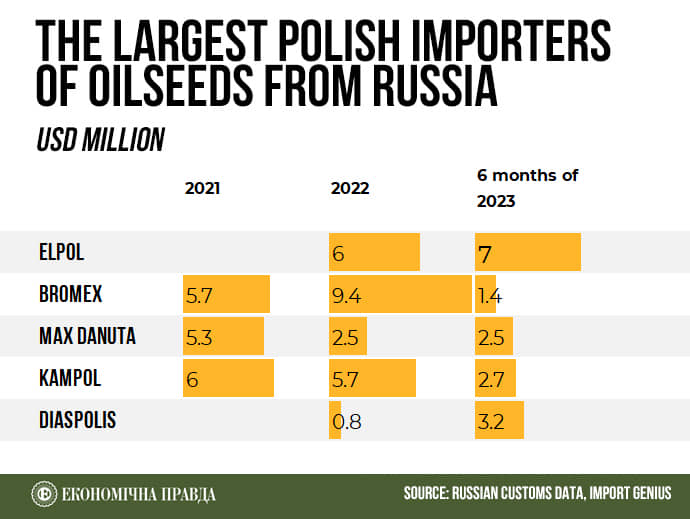

There are dozens of Polish companies that are willing to trade with the Russians. Having analysed the Import Genius data, Ekonomichna Pravda has identified the largest importers of oilseeds (mustard seeds, flax, etc.), which represent the bulk of Polish imports from Russia. Since April last year, Poland's imports of Russian oilseeds have exceeded those from Ukraine almost every month and have stayed at US£5-8 million per month.

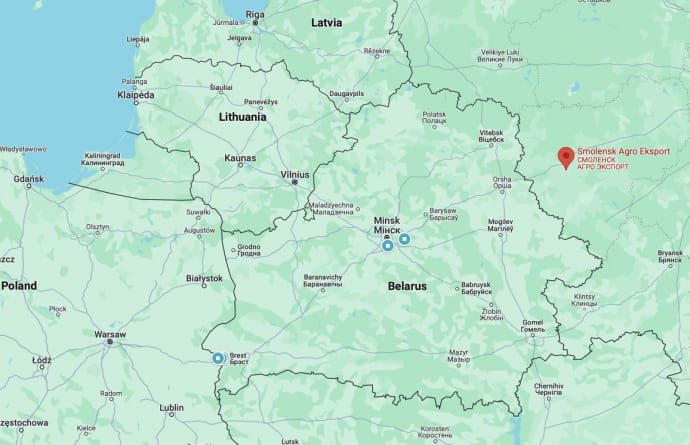

Elpol emerged as the leading importer of Russian oilseeds, purchasing US£7 million worth of goods in the first half of 2023 alone. In contrast, the company's imports of oilseeds from Russia barely exceeded US£6 million in the whole of 2022. Elpol mainly procured flax and mustard seeds, with Russia's Smolensk Agro Export Limited Liability Company (LLC) being the main supplier, likely chosen due to its proximity to the Belarusian border and the main road.

Other Polish importers also do business with the firm due to its convenient location; it is also the main Russian supplier to the Polish companies Piast, Bromex and MAX KROLIKOWSKA DANUTA.

However, the proximity of Russian companies' facilities to Belarus' borders is not always a decisive factor for Polish business. Companies purchase products from exporters in Moscow and even the Ural region, which lies over 2,000 kilometres (roughly 1,240 miles) away from Poland. Official trade data also shows an overall increase in agricultural imports to Poland as Russia's full-scale aggression against Ukraine rages on for the third year.

Most of the companies analysed by the Ekonomichna Pravda follow this trend. For example, imports from Russia by the Diaspolis company surged from US£800,000 in the whole of 2022 to more than US£3 million in the first half of 2023 alone.

Six of these companies alone imported oilseeds and grains worth almost US£20 million from January to July of last year, making up half of all imports in those categories. The second most popular Russian agricultural product in Poland is seed oil.

Last year, the value of seed oils imported decreased to US£3 million, compared to US£23 million in 2022. Nearly all of it consists of technical oils and fats, primarily imported by the Polish companies ENERGY WORLD, OLEOCHEMIA, and AGII.

For reference: Technical oils are defined under HS 1518. These are oils and fats of vegetable and animal origin that are used for industrial applications rather than human consumption, particularly by the energy sector.

Ukraine also exports them to Poland but in smaller volumes.

However, imports of Russian technical oil have not fallen so dramatically due to a sector-wide boycott, but rather the business decisions of only one company: Energy World, which imported US£22 million worth of oil from Russia in 2022, purchased only US£2 million in the first half of 2023. Many more companies are involved in the import of Russian agricultural products to Poland. Moreover, not all of them officially report such trade.

The editorial office has obtained the transcript of a conversation with representatives of the Polish company Agrolok which, at the request of Ukrainska Pravda, was contacted by an individual who posed as the manager of a Brest-based Belarusian company interested in establishing a rapeseed meal contract. The nature of the conversation makes it clear that the representative of the Polish company was willing to close such a deal. The representative was intentionally clued in to the fact that the fictitious grain was actually sourced from Russia, despite officially being labelled as Belarusian - a revelation that didn't sour his interest in the deal, judging by his request to receive further information by mail.

Another manager of the same company was more cautious about knowingly importing Russian products. "That's a whole other can of worms. To be clear, if the documents say it's Belarusian, then it isn't the end of the world," the company representative said in the audio recording. It should be borne in mind that the import of rapeseed meal, the commodity discussed in the call, from Ukraine has been banned by Poland since September 2023.

At the same time, the customs data analysed by Ekonomichna Pravda contains no evidence of any trade between Agrolok and Russian firms after 2017.

Conclusion

Not all these imports arrive in Poland in lorries, since the country's railway connection with Belarus is still operational. However, trade data reveals that while Polish protesters are blockading the Ukrainian border, in some cases halting non-agricultural shipments including humanitarian and military cargo in an attempt to gain additional leverage, the free trade of Russian agricultural products continues unhindered at its border with Belarus, and the volume of trade continues to grow as the war in Ukraine enters its third year. "Business is business", as the saying goes. On 29 February, Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk announced that Poland would thoroughly analyse the implications of Latvia's decision to ban imports of Russian food and did not rule out that Poland would take such steps itself.

That being said, the agricultural products mentioned here should also be added to the list of sanctioned products if Poland wants Russia to be defeated as much as the Ukrainians do.

Translation: Artem Yakymyshyn

Editing: Ben McBride, Teresa Pearce