Ukraine is still pumping Russian gas and financing the war against itself. Will this continue in 2025?

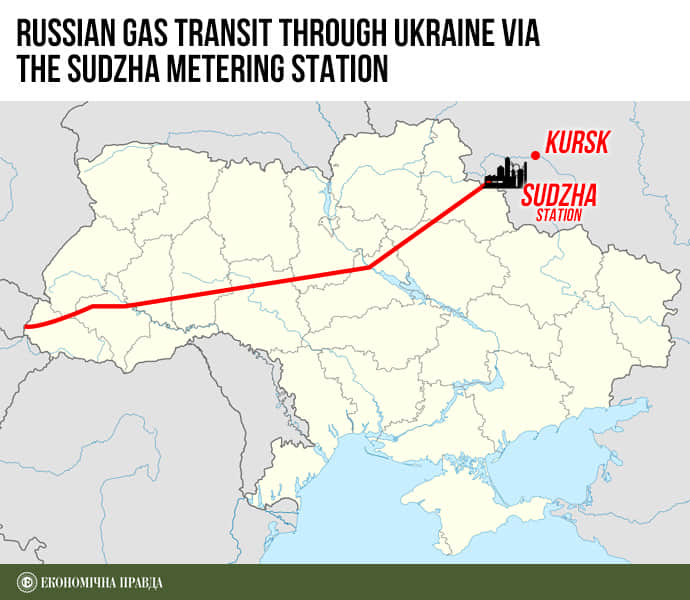

Russia has occupied parts of Ukrainian territory and caused immense damage to its energy infrastructure. Yet Ukraine continues to transport Russian gas to the European Union. Supply lines have remained uninterrupted despite the ongoing fighting in Russia's Kursk Oblast, where the Sudzha gas metering station - the sole entry point for Russian natural gas into Ukraine's transmission system - is located.

The reason for the policy lies in Ukraine's obligations to EU countries under the five-year transit agreement, which expires on 1 January 2025. However, this does not necessarily mean that the flow of Russian gas through Ukrainian territory will end.

Advertisement:Discussions around potential scenarios for the continuation of transit have become more frequent, with one possibility involving Azerbaijan as an intermediary. But what is the true motivation behind this?

Events in Sudzha: how the fighting affected gas transit and prices in the EU

In the early hours of the Ukrainian offensive in Kursk Oblast, which began on 6 August, the Sudzha gas metering station on the Russo-Ukrainian border fell to Ukrainian forces.

Sudzha is the sole facility through which Russian gas has been supplied to the European Union in recent years. The fighting near the station inevitably raised concerns about the feasibility of continuing natural gas transit. On the morning of 7 August, Ukraine's Gas Transmission System Operator (GTSO) reported that the transit of Russian gas was ongoing, without interruption. "The applications [for transit - Ekonomichna Pravda] have been confirmed, and the flow of gas is maintained," the Ukrainian company stated.

That day, the transit volume totalled approximately 39.5 million cubic metres, 6% below the standard level. However, it later recovered to an annual average of 42.4 million cubic metres. At present, the transit of Russian gas remains at maximum capacity.

How did the Sudzha events affect gas prices? They rose by a few per cent in the early hours of the Ukrainian offensive in Kursk Oblast but eventually stabilised. A week before the offensive, natural gas in the EU was priced at US£400 per 1,000 cubic metres.

However, after a week of intense hostilities, the price increased to US£455 per 1,000 cubic metres.

Sudzha gas distribution station before Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine.Photo: Google.com

Sudzha gas distribution station before Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine.Photo: Google.com

Given the scale of the border events, analysts consider even such a slight increase in gas prices to be speculative, as there is no current risk of a halt or reduction in Russian gas supplies. Despite the hostilities near the gas metering station, Ukraine has reaffirmed its status as a reliable transit country.

Sudzha gas distribution station after the Ukrainian offensive.Source: x.com

Sudzha gas distribution station after the Ukrainian offensive.Source: x.com

Things could have turned out differently. The most striking event occurred in August 2022, when Russian energy giant Gazprom artificially inflated gas prices in the EU to US£3,000 per 1,000 cubic metres.

Following this, prices in EU countries dropped to US£300-400 per 1,000 cubic metres.

Why is Ukraine transiting Russian gas?

Kyiv and Moscow signed a five-year transit contract at the end of 2019. Ukraine sought the agreement for several reasons. Economically, the transit provided Kyiv with billions of dollars.

A portion of this revenue was allocated to maintaining the gas transmission system (GTS), while the remainder was added to the state coffers. Additionally, as part of the agreements, Russia committed to paying Ukraine nearly US£3 billion in debt awarded under the Stockholm arbitration. [The Stockholm arbitration refers to a legal dispute between Naftogaz, a Ukrainian state-run national oil and gas company, and Russia's Gazprom. In 2017, the arbitration court found Gazprom in breach of its contractual obligations under the 2009 gas supply and transit agreements and mandated that Gazprom pay Naftogaz £4.63 billion for failing to deliver the agreed gas volumes for transit - ed.].

The second reason was that the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline was nearing completion, with only 30-40 km of pipes left to be laid. This would have allowed the Russians to abandon the services of the Ukrainian GTS, leading to Kyiv losing transit, money, and leverage over the Kremlin. The third reason, discussed off the record by those involved in negotiations, was that transit was seen as one of the few levers of influence capable of deterring Moscow from launching a full-scale war.

Unfortunately, the war did break out, despite hope that this factor would avert it. However, even on day 903 of the Russo-Ukrainian war, Russian gas continues to flow to the EU as usual. Why is this happening and does Ukraine benefit from it?

Transit economics

Ukraine had the full right to declare force majeure on the first day of the full-scale Russian invasion and halt the transportation of Russian gas through its territory, but did not do so.

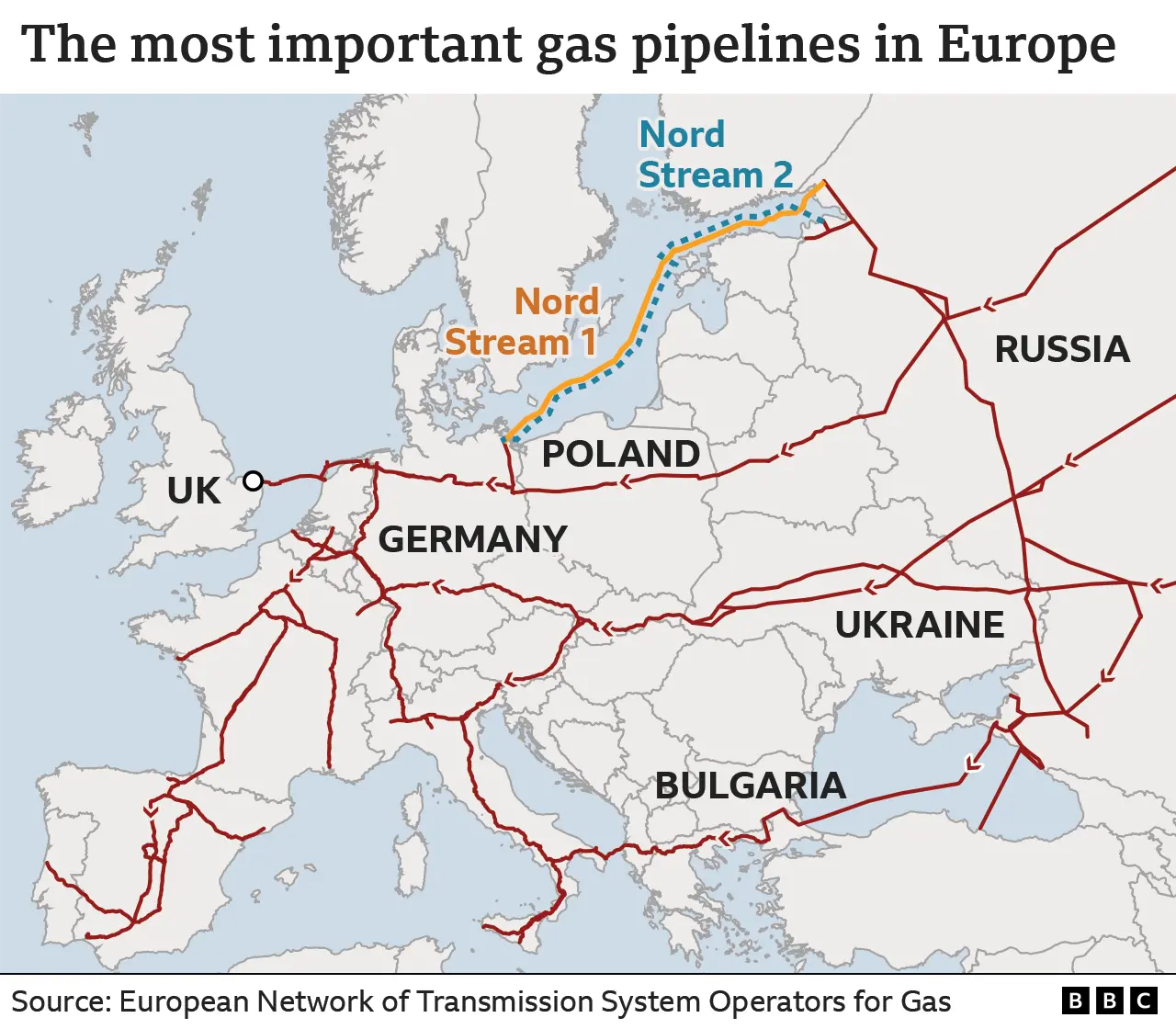

The primary reason was that, two years ago, not all EU countries were prepared to immediately find alternative gas suppliers, and transitioning took time. Before the war, Gazprom supplied 150-155 billion cubic metres of natural gas to the EU annually, accounting for about 40% of the bloc's total gas imports. A total of five gas pipelines run from Russia to the EU through third countries.

Both Nord Stream pipelines have been shut down, and the Yamal-Europe gas pipeline, with a capacity of 38 billion cubic metres per year, is also blocked.

Gas supplies to the EU are currently routed through the TurkStream and Blue Stream pipelines via Turkiye, Southern and Southeastern Europe, and through one of the two entry points into the Ukrainian gas transmission system. As some of these nations are Ukraine's strategic partners, providing Kyiv with financial and military assistance, gas transit continues. How much does Russia make from all this?

Gazprom transports 12-14 billion cubic metres of gas annually through the Ukrainian GTS, earning about US£5 billion. Ukraine's GTS Operator receives US£700-800 million annually from transit fees. The lion's share of these funds is allocated to transportation costs, particularly the purchase of fuel gas for compressors and the maintenance of the gas transmission system.

If Ukraine ceases transit after 2024, when the current agreement expires, it will miss out on US£800 million in annual revenues, while Gazprom will suffer a loss of US£5 billion.

Transit after 2024: pros and cons

Ukraine's public stance on continuing transit from 1 January 2025 is "no negotiations or agreements with Gazprom and the Russians". However, such a position does not mean that there will be no supply. "Naftogaz is not going to negotiate an extension of the agreement with Gazprom.

On the other hand, the Ukrainian state possesses a key strategic asset - the gas transmission system. It is of utmost importance for us to keep the GTS working," said Naftogaz CEO Oleksii Chernyshov. "One of the proposals currently under discussion is to replace Russian gas with supplies from Azerbaijan.

This is what government officials are doing now," President Volodymyr Zelenskyy stated in early July. Ukraine's Energy Minister Herman Halushchenko noted that Kyiv currently has no concrete proposals for transiting Azerbaijani gas. "I always say we need to have a specific document on the table.

So far, there is no specific proposal that can be discussed. We will talk once possible initiatives become practical proposals," the minister added. What do industry experts and market participants think about the potential transit extension?

Serhii Makohon, former Head of the Ukrainian GTS Operator, has been a consistent advocate for ending transit after the expiry of the current contract. "Gazprom generates about US£5 billion a year from transit, while Ukraine receives US£800 million, but most of this money is spent on transit itself. [Ukraine's] treasury receives US£100-200 million in taxes and dividends. If we compare these figures, I don't see much economic sense in doing this [continuing the transit]," Makohon says.

He believes the Kremlin also views gas as a political influence on Slovakia and Hungary. "The parties of [Slovak Prime Minister Robert] Fico and [Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor] Orban are quite pro-Russian. We frequently hear their remarks about their efforts to block aid to Ukraine," Makohon adds. Mykhailo Honchar, Head of the Kyiv-based think tank Strategy XXI, also supports halting transit. "In times of war, priorities somewhat differ from when commercial approaches dominate.

You cannot let the enemy earn money and feed their war chest. We should not make a tragedy out of the absence of transit," he said.

Azerbaijani or Russian supplies

Honchar views the idea of transiting supposedly Azerbaijani gas as a "hoodwinking tactic." He says that, in reality, it would be Russian gas being transported under the guise of Azerbaijani supplies. "Azerbaijan currently has no available gas for transit through Russia and Ukraine to the European Union.

Everyone understands perfectly well that it will be Russian gas disguised as Azerbaijani gas. This would be a swap, where SOCAR [the Azerbaijani state-owned oil and gas company] buys gas from Gazprom, and the fuel, documented as Azerbaijani, is then transported to the EU. Why would we want that?" Makohon wonders.

According to Honchar, behind the proposal could be a scheme to benefit the Kremlin. "The funds that some Gazprom-affiliated company with European registration will receive will not flow to Russia, but will remain in the European Union. These funds can be used to purchase various critical equipment and materials that Moscow needs to produce missiles and precision weapons.

This equipment could then be legally transported through Azerbaijan to Russia. Therefore, when we discuss the continuation of transit, we should be looking at the military sphere, not the gas sector," he says. Makohon also believes that the Azerbaijani gas issue involves corruption and scheming.

"If the EU needs gas, let's do everything transparently. Let's tell the Russians: 'If you need transit, give us back the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, stop targeting our energy sector, and on top of that, we will introduce an additional duty on the transit of your gas'. For us, this is an additional US£2-3 billion for energy sector recovery.

It will be transparent and clear, otherwise I see no point in agreeing to transit some Azerbaijani gas that does not even exist," Makohon concluded.

Translation: Artem Yakymyshyn

Editing: Rory Fleming-Stewart