“I'm not a Ukrainian nationalist, I'm Hungarian, but this is my country”: the gardener from Ukraine's west who has been fighting in the infantry for three years

Gy?z?, 50, is an infantryman in the 128th Separate Mountain Assault Brigade from Zakarpattia (Transcarpathia) in Ukraine's west. You could say he's representative of the current infantry of the Armed Forces of Ukraine - a former civilian, aged 50+, an ordinary worker in peacetime. But that's not quite the case.

What makes Gy?z? unique is indicated by his name. He's an ethnic Hungarian, his native language is Hungarian, and in addition to Ukrainian citizenship, he also holds Hungarian citizenship, a fact he doesn't conceal. A short, slim, bespectacled man, Gy?z? lacks all the "heroic" attributes of the formidable Ukrainian soldier: he doesn't glare fiercely from beneath his brow on social media, he has no patriotic tattoos, nor has he grown a beard that requires daily upkeep.

He's "merely" involved in active combat, coming face to face with the enemy, has been wounded multiple times, once dragged a fallen comrade's body for two kilometres, and has taken several Russian soldiers prisoner.

Advertisement:"They asked about my eyesight at the Military Medical Board. I said one eye is -6 and the other one -7. 'That's fine - fit for service. Do you have all your teeth?'"

Someone like Gy?z? could only be from Zakarpattia - from a small Hungarian-speaking village near the town of Berehove, to be precise.

He's a genuinely ordinary working man who, as an ethnic Hungarian, obtained Hungarian citizenship 15 years ago, which enabled him to travel to the European Union a few times and work there legally. Before Russia's full-scale invasion, Gy?z? worked as a gardener in his village, taking care of the gardening at several cemeteries, a kindergarten, and other municipal facilities. He recalls that when he started the job, the local council used to demand daily photo reports of the work he'd done.

But once they saw that Gy?z? was hard-working and responsible, they left him to it. As a gardener, Gy?z? was paid the minimum wage. But the job had its advantages - he got on with the work himself and was his own boss.

On 24 February 2022, the first day of Russia's invasion, Gy?z? received a phone call from the local council informing him that as an employee of a municipal institution, he had to report to the military enlistment office. Gy?z? went, and he was mobilised that very day. Why this happened remains a mystery.

He was no spring chicken; he didn't have a military specialism that was in short supply; and this was at the beginning of the war, when not everyone was being drafted indiscriminately. Perhaps his conscription service, which he completed back in 1990-1992, played a role. Here's how the soldier himself describes his Military Medical Board experience - it's a classic.

"They asked about my eyesight.

I said one eye is -6 and the other one -7. 'That's fine - fit for service. Do you have all your teeth?' I had two missing at the time, but later on, four more got knocked out when a drone hit my shoulder in Robotyne..." Thus Gy?z? became an infantryman in the 128th Separate Mountain Assault Brigade.

He remains a private and a rifleman to this day - lowest rank, lowest position. A few other "lowest" descriptors could be added. Serving as a private in an assault unit is the hardest, most dangerous, most thankless task.

The word "worst" comes to mind as well, but that wouldn't be accurate. The worst is finding yourself in a newly formed unit with incompetent commanders.

Advertisement: In nearly three years of war, the former gardener has become an experienced assault infantryman.Photos provided by Gy?z?

In nearly three years of war, the former gardener has become an experienced assault infantryman.Photos provided by Gy?z?

Aside from his Hungarian heritage, Gy?z? stands out in another way - he doesn't have an alias. With a name like his, that's probably not surprising.

For the former gardener, the war began in Zaporizhzhia Oblast. Together with his comrades, he dug trenches and built dugouts, where they would take cover from artillery shelling and the Russian helicopters that brazenly flew directly over their positions firing unguided aerial rockets at the infantry. It took several successful launches of Stingers and Iglas (man-portable infrared homing surface-to-air missiles) to put an end to the choppers' audacity.

But it wasn't until he got to Kherson Oblast that Gy?z? looked the enemy in the face. His brigade carried out relentless assaults as they liberated settlements. "One group in particular is lodged in my memory - some kind of Russian special forces," Gy?z? recalls. "They were positioned not far from us, and they'd periodically pop up at full height, unload their entire ammunition stock at us and duck back down again.

They acted like Rambo - they were either trying to impress us with their fearlessness or psyching themselves up. Completely reckless. Later we took their load-carrying equipment and weapons..."

During one of the assaults, Gy?z? and his comrades captured a Russian sniper. "Our unit was advancing on the katsaps' [Russians'] positions with a tank in front and an infantry fighting vehicle behind us. The tank was moving forward with its mine rollers lowered, while the IFV stopped in front of a strip of forest because the area was heavily mined.

We got out and went in between the trees. The katsaps managed to flee, but in their haste they left a lot of equipment behind. Near the trenches, there were tank shells and metal barrels filled with diesel fuel - a refuelling and reloading point for their tanks.

We had just crouched down near the barrels when a shadow flickered nearby. I radioed the commander, warning that there might still be katsaps around, and the tank raked the area with machine-gun fire. We followed up with bursts from our rifles and grenade launchers."

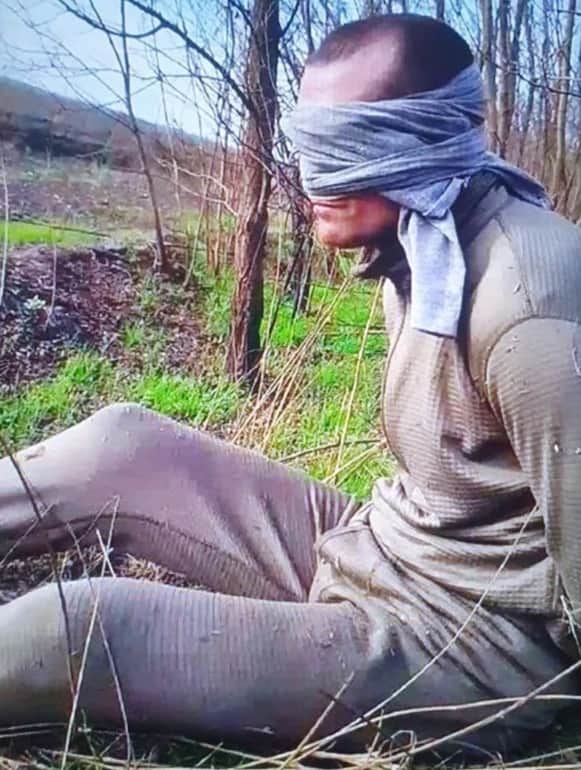

It later turned out that the assault troops had wounded a Russian: one bullet had pierced his body armour. The soldiers had a rough idea of where he was, but they approached him from the sides, while he was waiting in front - sitting against a tree, holding an SVD sniper rifle, ready to open fire. "We took his weapon, removed his body armour and blindfolded him.

The sniper hadn't had time to get rid of his ID - he was a contract soldier. We handed him over to the rear. We knew that if the katsaps had captured one of our snipers, he probably wouldn't have lived for more than a minute.

But at that moment there was no anger, no urge to kill at all costs..." A few days later, the infantry unit had to employ a new combat tactic - storming a village in civilian transport. "We set off in one IFV, but on the way it overheated.

Another vehicle arrived, and we quickly moved everything into it, climbed on top, and off we went. But as we drove through a forest strip, the IFV hit a stump and 'threw a shoe' - the track came off." The squad commander radioed for his Land Rover and two Techniks (four-wheel-drive Volkswagen vans) so they could complete the combat mission.

The assault troops got in and sped into the village. "As we entered, we saw another one of our IFVs near the first few houses," Gy?z? went on. "There were infantrymen lying around it, taking cover from enemy fire. We drove past them and stormed into the street.

The barrel of a Russian tank was sticking out from a window of one of the houses - and it wasn't firing. The gunner must have been so stunned by our cheek that he hesitated. We sped past, but then we were hit with cluster munitions from the air.

We turned at a crossroads, raced to the other end of the village, got out and began mopping up the houses. We entered in pairs, checking the rooms and cellars. We found an Ural truck loaded with 120mm mortar shells in one yard, Shmel flamethrowers in a garage, shells, Mavic batteries and loads of gear.

We could hear Russian tanks rumbling away, retreating from the village... Then this elderly woman came out of a house. She couldn't believe we were Ukrainian forces - we had to show her our military IDs.

I still had my old Soviet one, but it was obvious I wasn't Russian..." Close combat has made Gy?z? a cautious and cool-headed soldier who understands that emotions have to be set aside if you want to survive. "In Bakhmut, the Wagner fighters often pretended to be dead - they'd cover themselves with sheets of metal roofing, with only their legs sticking out.

You'd walk past, and suddenly they'd get up and shoot you in the back. Since then I've got into this habit - if you see an enemy body and you aren't certain it's a corpse (if it's been lying there for a long time, it's obvious), you fire a confirmation shot. That's what our foreign instructors taught us.

Because the enemy might be wounded, unconscious, or in shock - and then he might shoot you in the back."

Advertisement: One of Gy?z?'s fighting positions.Photo: Gy?z?Advertisement:

One of Gy?z?'s fighting positions.Photo: Gy?z?Advertisement:

"We captured this soldier who kept on mumbling 'Kill me, kill me...' He was driving me nuts!"

A close friend of Gy?z?, Oleh Kurtash, was killed fighting in Donetsk Oblast. "A piece of shrapnel hit him in the head. He was 32.

I dragged him for two kilometres, even though there were Wagner fighters nearby and mines exploding all around us. You have to retrieve the fallen if it's at all possible, not put it off, because most likely it won't be possible later on..." Gy?z? has retrieved many fallen soldiers, sometimes with his own hands, sometimes using an MT-LB (a tracked armoured fighting vehicle).

He's been wounded multiple times himself and has lost count of the number of times he's been concussed. "The first time I was wounded was back in 2022, when a piece of shrapnel got stuck in my leg. I dug it out myself with a knife and bandaged it up.

Then I got another piece of shrapnel in my back from a kamikaze drone. Two of my comrades, Kachan and Kozlyk, were killed right next to me. But I went on the assault because my wound wasn't serious.

In Robotyne [Zaporizhzhia Oblast], a drone exploded inside the dugout and knocked out four of my teeth. We'd taken over a Russian dugout. I camouflaged the entrance with acacia branches and stacked a few katsap body armours on top for extra security.

There were enemy drones constantly flying overhead, watching us. One explosion cleared a way through and another drone flew right inside. What saved me was a Russian sleeping bag that I managed to throw over myself.

The blast wave threw me out of the dugout, and shrapnel scraped my arm. I was in shock and couldn't move at first, but I snapped out of it quickly." Gy?z? managed to take a prisoner at that position.

"Their commanders were sending katsaps straight into our firing lines, telling them it was the grey zone. There were only three of us on that position: two digging, one keeping watch, then we'd rotate. I was on guard when I got a warning over the radio: a drone had spotted a katsap nearby.

Then I saw him myself - he'd stepped into a crater. I warned the guys to put down their shovels and grab their weapons. I hid in the bushes and waited.

When he got within 10 metres of us, I jumped out, aimed my rifle at him and barked: 'Hands up!' He froze, he was completely stunned, not realising how close he'd got to us. He wasn't warmly dressed, even though it was winter. And he was soaking wet, as it had been snowing and raining before."

The prisoner put up no resistance. Judging by his military ID, he was a 49-year-old contract soldier from Krasnodar. "He was married - he had a wedding ring on.

We took away his rifle, body armour and knife, then told him to sit quietly until we could get him to the rear. But he started mumbling: 'Kill me, kill me!' I told him, 'I'm not going to kill you, I'm going to swap you for one of our soldiers.' But he kept on repeating: 'Kill me, kill me...' He was driving me nuts! Together with Archie (our current company commander), we later took four more prisoners - scouts who had a local guide with them.

They started spinning tales about how they hadn't been fighting and hadn't shot anyone. We took them to a farm and handed them over. Even gave them some tea before that."

Gy?z? has often had to shoot at close range, but he doesn't keep count of the number of Russians he has killed. "I don't know and I don't want to know. I remember every fallen comrade, I can name them all.

But the enemy doesn't interest me. I understand that I could die too, it's happened so many times. But when I go to the contact line, I don't think about it.

It's only on the second or third day after returning that I start feeling anxious. That's when I take deep breaths and tell myself: nyugi, felejtsd el! (Hungarian for 'Calm down, forget about it!')"

Advertisement: An ethnic Hungarian from Zakarpattia, Gy?z? may not look like a fearsome fighter, but he is one of the best and most experienced in his company.Photo: Gy?z?

An ethnic Hungarian from Zakarpattia, Gy?z? may not look like a fearsome fighter, but he is one of the best and most experienced in his company.Photo: Gy?z?"My comrade begged me: 'Let me go, Gy?z?, I need to get married - will you replace me?' How could I not? If it's important, then go"

For a long time now, Gy?z?'s unit has been holding a village that was recaptured from the Russians in the summer of 2023.

The hardest part now is getting in and out of their positions due to the constant threat from drones. Combat "deployments" drag on, with no replacements for the infantry. The fortified positions of his mountain assault company resemble an underground town, with tunnels dug between the basements and cellars of ruined houses.

Gy?z?'s longest "deployment" lasted four months (!). Since he is the most experienced, knows how to do everything and has the worst possible trait for the army - he never says no - his comrades often ask him to stay longer. The same fate that had the Berehove enlistment office examining him like a horse, checking his teeth, has followed him to the battlefield - he remains the unit's workhorse.

"Our combat deployments usually last no more than two months, but things don't always go to plan. There was a young guy in my group who had planned his wedding. He'd been there for a month and a half and was supposed to rotate out, but there was no one to replace him.

So he begged me: 'Let me go, Gy?z?, I need to get married - will you replace me?' How could I not let him go? If it's important, then go." The firing position measures just 10 square metres.

Yet because of the constant drone threats, the infantry sometimes have to stay put for three to four days straight, unable even to stretch their legs. Provisions, ammunition, cigarettes, gas canisters, trench candles and so on are dropped by drones. They cook their own meals.

After a month of being cooped up in these conditions, in constant danger, people start going a little nuts. "I force myself to keep busy, checking the perimeter, looking for weak spots, digging new firing positions. Once I got within 15 metres of the katsaps without even realising it."

During his longest deployment, Gy?z? even contrived to wash four times. He heated water in a basin over some trench candles, then poured the melted wax into new candles to keep them going. Better than wet wipes anyway.

"The Russians only attempted one assault during that whole time. We f**k them over with small-arms fire. But the attacks from mortars, artillery and drones were constant, 24/7.

Psychologically, it was tough. Some of the guys even ordered anti-anxiety pills, which were dropped in by drone. There were a few attached intelligence officers from a neighbouring brigade in my group.

They'd been with us for a month and were due to leave, but their deployment was extended by two weeks due to the drone threat. One of them thought it was my doing as the senior in the group and started having a go at me: 'Who do you think you are? You're not even Ukrainian!' He called me all sorts of names.

I replied: 'I may not be Ukrainian but I've been here longer than you.' He never brought it up again. He even wanted us to take a photo together later..." The only means of communication at the positions is radio.

A Russian chopper detected the Starlink and destroyed it with a missile. The long periods of being unable to contact their loved ones at home are yet another psychological burden for the soldiers.

Advertisement: The Russian sniper captured in Kherson Oblast.Photo: Gy?z?

The Russian sniper captured in Kherson Oblast.Photo: Gy?z?

"I don't have anyone but my mother. She's 70, and she used to work in intensive care at the district hospital.

She's retired now and suffers from diabetes. In the first few months I told her I wasn't on the contact line, but she didn't believe me and kept asking me to turn on the video. So I had to come clean."

Before going on lengthy combat deployments, Gy?z? would warn his mother that he wouldn't be in touch for a month or two, and she put up with it. But when the silence dragged on for longer, she would become extremely worried and start calling his comrades. "That's when the senior sergeant contacted me over the radio, called my mum from his own phone and put it on speaker so we could talk.

The guys were amused by our Hungarian - they couldn't understand a word. They know I have Hungarian citizenship and they're fine about it. Mum's holding on, despite her age and her illness.

She still does the housework, but she can't manage the heavy labour anymore, so when anyone from my area goes on leave, I ask them to stop by and see if she needs help." Gy?z? has been home on leave himself, and he admits that not everyone in his home village understands his decision to join the Armed Forces of Ukraine. "Some people say I didn't have to join the army, I could have gone abroad like other people have done.

I don't care, they can say what they want. I joined because it's my duty. I'm not a Ukrainian nationalist, I'm a Hungarian, but this is my country.

If everyone runs away, then who's going to kick the Ruscists' asses?" Author: Yaroslav Halas, officer in the 128th Separate Mountain Assault Brigade, especially for Ukrainska Pravda. Zhyttia

Translation: Anastasiia Yankina, Tetiana Buchkovska

Editing: Teresa Pearce