Has Russia's invasion changed Dutch public opinion on Ukraine …

Back in 2016, when the Netherlands held a national referendum on the European Union's association with Ukraine, Dutch voters weren't overly concerned about the treaty compromising the EU's relationship with Russia. Instead, it was predominantly opposition to European integration that spurred the 'against' vote. While dissatisfaction with their national government also played a substantial role in the referendum outcome, it did not nearly predict people's vote as much as considerations that had to do with the treaty's content or consequences.

A brief history of referendums in the Netherlands

Let's back up a little.

The Netherlands held its first consultative referendum in 2005, asking its citizens whether they were in favour of their country ratifying the European Constitution. This referendum was made legally possible only through the introduction of a bespoke, one-off law. A little over six out of ten voters ticked the box against ratification, with a relatively low turnout.

The European Constitution was shelved as the Netherlands, along with France and several other countries, were unable to ratify the treaty. It would not be until ten years later, in 2015, that more comprehensive referendum legislation was established, even though the country's largest party - the People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) - opposed it. Shortly after, in 2016, a second consultative referendum on an EU-related topic took place.

Grassroots organisations in the Netherlands collected sufficient signatures to call a referendum in which citizens were asked whether the EU should sign an economic association treaty with Ukraine.

The campaign against the EU's association with Ukraine

This movement was spearheaded by, among others, the Forum for Democracy (FvD), which back then was still a think-tank and not yet the prominent political party it became in 2019, as well as other citizen-led organisations like Burgercomite-EU and the Geenstijl blog. The no-campaign was furthermore supported by parties on both extremes of the political spectrum, such as the Socialist Party (SP), the Party for the Animals (PvdD), and the Party for Freedom (PVV). Their outspoken anti-elitist rhetoric emphasised what they called the excessive powers of the "bureaucratic" supranational EU-institutions and "corrupt" establishment elites, as well as the negative impact of potential free movement of labour from Ukraine on the Dutch job market and social security.

Moreover, aside from the legitimacy of the EU and economic considerations as central arguments in the campaign, the "No" camp argued that the association treaty would provoke Putin.

Theories of referendum voting

These arguments are reflective of two prominent theories that govern EU referendum voting. The 'issue-based' theory of referendum voting posits that the referendum vote is largely driven by the subject matter at hand, in this case the economic association of Ukraine with the EU. It can be broadly interpreted not only to include approval or disapproval with the terms of the treaty at hand, but to encompass more generic attitudes towards European enlargement and integration, as well as more extensive consequences of the association such as the EU's relationship with Russia - a fierce opponent of the treaty.

The second-order theory of referendum voting, on the other hand, sees EU referendums primarily as tools for citizens to express their discontent with how their country is being run. It contends that the referendum vote is a vote of support for or condemnation of the incumbent national government or sentiments about national politics more generally.

What can the 2016 Dutch referendum tell us about these theories?

During the 2016 Dutch referendum, we fielded a series of four survey questionnaires to over 20,000 respondents. We included items that map to the issue-based theory of referendum voting, such as how favourably people saw European integration, or to which extent they believed Ukraine needed to take a neutral position between the EU and Russia.

We also included items that correspond to the second-order theory, such as satisfaction with the government and items measuring political cynicism. We compare three logistic regression models where (almost) all these predictors are standardised. This allows us to compare specific predictors' effect sizes, as well as the explanatory power of each model.

The first model tests all issue-based predictors, the second tests all second-order predictors, and the third combines the predictors of both theories. The results provide overwhelming evidence that attitudes towards European integration are, by far, the strongest predictor of the vote against treaty ratification. On the other hand, people's rating of their national government still carried a substantial amount of predictive power, but not nearly as much as sentiments towards the EU.

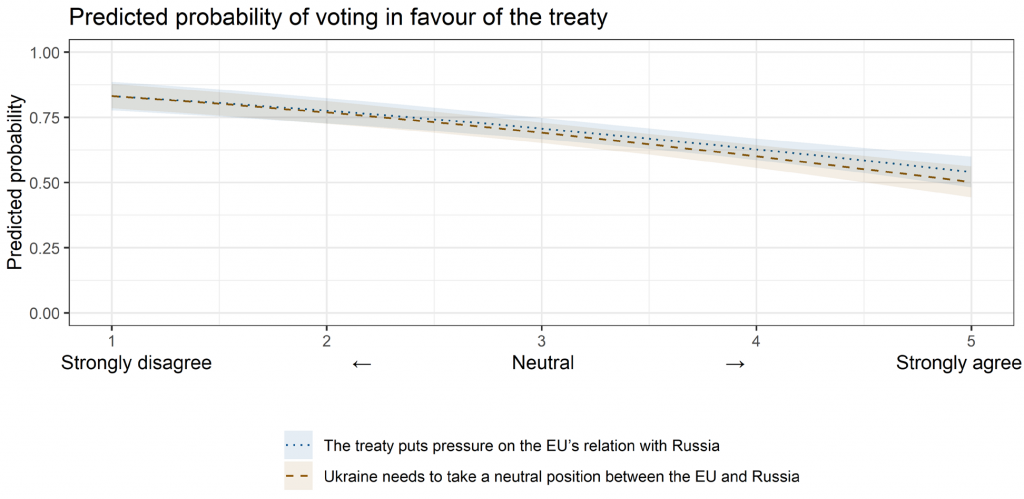

Figure 1: Impact of views concerning the EU's relationship with Russia on support for the association treaty with Ukraine  In addition, as Figure 1 illustrates, the two items we included about Ukraine show that people who were concerned the treaty may jeopardise the EU's relationship with Russia were less inclined to vote 'yes' in the referendum.

In addition, as Figure 1 illustrates, the two items we included about Ukraine show that people who were concerned the treaty may jeopardise the EU's relationship with Russia were less inclined to vote 'yes' in the referendum.

The 10% of people most concerned that the treaty may put pressure on Russia were 35% less likely to vote for the treaty than those with average opinions. Similarly, the 10% of people who most strongly felt that Ukraine should stay neutral were 42% less likely to vote in favour.

Impact of the war in Ukraine

Back in 2016, Russia was presumably not nearly as big a factor in people's considerations as it would be today. In a more recent survey, we asked people why they favoured or opposed Ukraine's bid for accession to the EU.

This survey was fielded at the end of July 2022, during Russia's war on the country. People in support of Ukraine's EU bid frequently mentioned the willingness of Ukrainians to become European Union citizens as a decisive factor. Nearly one in three supporters mentioned Russia's aggression when asked why they favour the Ukrainian EU-bid, as opposed to one in five of opponents mentioning Russia.

The difference in proportion of people referring to corruption as a problem in Ukraine between those in support and those against EU accession was much starker, with fewer than 7% of people in favour mentioning corruption, as opposed to over 40% of those against. Corruption is a big impediment for accession to those who oppose Ukraine's bid. In addition, those respondents tended to mention that the war is not a reason to welcome the country with open arms.

While the EU's stance towards Ukraine's accession is predominantly symbolic at the moment, it is meaningful and demonstrates the soft-power resolve that the EU prides itself on.

Should the Dutch be presented with another consultative referendum about Ukraine's accession, it appears that issue-based notions will remain a defining force in the voting outcome, providing us with lessons when it comes to framing narratives about the war, Ukraine's place in Europe, and the EU's role in peace on the continent.

For more information, see the authors' accompanying paper in European Union Politics