How Western energy sanctions against Russia are failing

Instead of imposing harsher sanctions after the events of 2014 [start of Russia's hybrid war in the eastern part of Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea - ed.], Western companies helped Russia master gas liquefaction technologies and bring production to a new level. Western countries have fiercely fought "oil" dictators in Iraq, Iran, Libya and Venezuela, yet are missing the biggest one right under their noses. The US, the UK, and the EU have not only been importing Russian oil and gas for decades, but they have also been building pipelines, driving out other, smaller importers and helping Russia master production and transportation technologies.

The second year of the Russian invasion of Ukraine has seen the emergence of many loopholes and gaps in the energy sanctions against Russia. The oil embargo and black gold price caps imposed on Russia are not taking effect in full, and the notorious gas supply is not subject to sanctions at all.

Advertisement:The confrontation around sanctions is increasingly resembling a race, with the winner two steps ahead of the opponent. The outcome of this competition is clear to see: Russia retains its primary source of income, and energy sanctions are having no effect on the Kremlin's desire to end the war.

Sanctions once again come late

Until 2014, the maintenance of deep oil and gas wells in Russia depended almost entirely on four American companies.

A former employee of Halliburton's Russian subsidiary told EP that in some cases they had to complete challenging wells themselves because local contractors were unable to do so on their own. This means that Russia could have been brought to its knees back in 2014 if these companies had been forced to leave Russia. However, the political will was lacking.

The sanctions in place at the time were too weak to cause significant damage to Russia. However, they were strong enough to force the Kremlin to brace itself for truly severe blows. Immediately after occupying Crimea, the Russians launched an import substitution programme.

At the time (in 2014), they had the capacity to provide only 20% of the equipment required for drilling operations; this figure increased to 50% in 2019. US companies remained involved in the supplying services to Russian wells and in training drilling specialists at modern training centres in Russia.

Western companies have played a key role in assisting the Putin regime in developing liquefaction technologies, enabling Russia to transport gas by tanker worldwide and thus to become less dependent on pipelines to the EU. Russia's largest Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) projects, Sakhalin-2 and Yamal LNG, were brought to life through Western technology licences.

French, UK and Japanese companies acquired shares in these projects.

Western countries supplied equipment and materials for oil refining until 2022. Annual contracts worth billions of US dollars helped modernise Russian refineries and consolidate their position in this market. Following the occupation of Crimea, the European Union not only continued to purchase oil and gas from Russia but even increased the volumes.

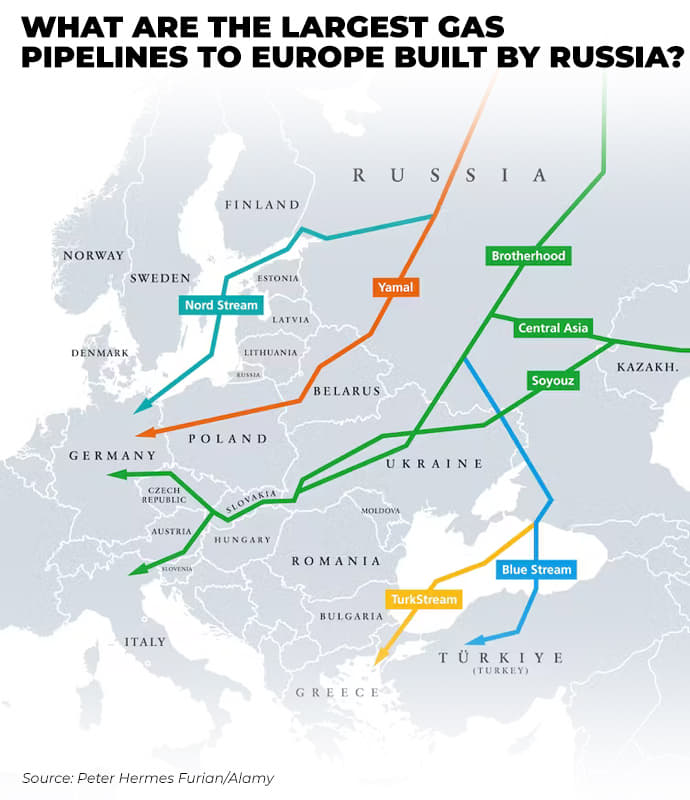

The EU's dependence on Russian gas imports increased from 37% to 45% between 2014 and 2019. Lobbyists helped Moscow build a network of Russian-controlled gas pipelines in the European Union and tried to make customers forget about the war in Ukraine [ongoing since 2014 - ed.]. Russian gas was ultimately made part of the EU's Green Deal.

The EU, the UK, and the US have effectively given the aggressor superprofits.

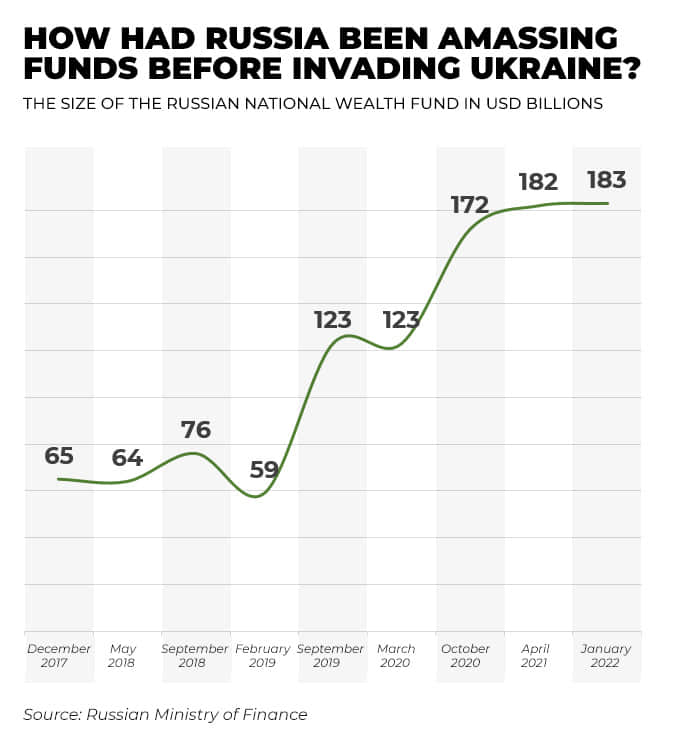

In the years leading up to the full-scale invasion, the Kremlin was putting some of this revenue into the National Wealth Fund (NWF). The funds held there reached US£183 billion. The NWF is currently used to finance weapons production and salaries for the military, among other things.

Western countries did not stop feeding Putin's regime even after blatant crimes committed under the Russian flag.

The oilfield services company Schlumberger has been kept busy drilling complex Russian wells, while Japanese firms are still involved in the Sakhalin-2 LNG project, as no sanctions have been imposed on gas supplies.

Read also: The Devil Wears the Russian Soldier's Uniform. How they tortured people in Kyiv Oblast

The oil embargo was even postponed for a year [after the full-scale invasion - ed.], and an exception was made for one of the branches of the Druzhba (Friendship) pipeline. The results of these partial sanctions are controversial.

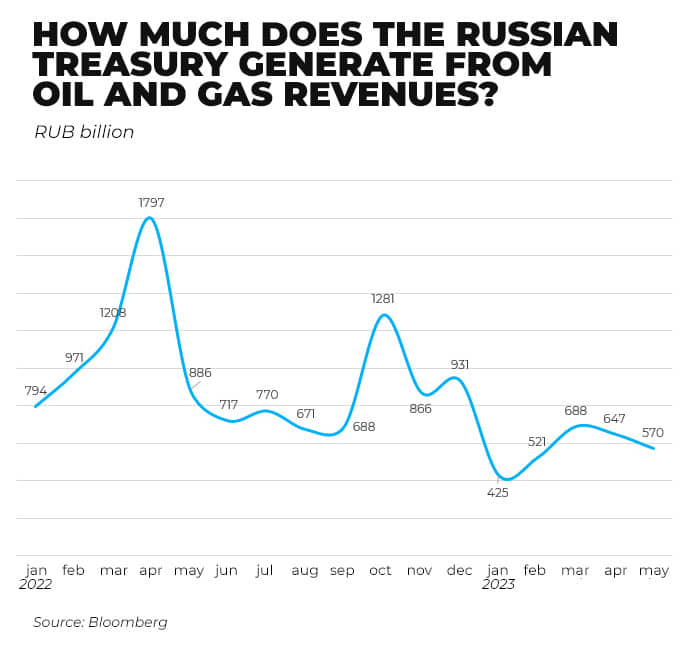

On the one hand, by May 2023, Russian treasury revenues from oil and gas sales had fallen by 38% to RUB 570 billion [roughly US£6,2 billion]. On the other hand, the comparison with 2022 is not entirely accurate, since oil and gas prices were then at their historical highs.

Regardless of the loss in excess profits, the aggressor still has enough money to finance the war. The federal budget deficit in June exceeded the annual plan and amounted to RUB 2.6 trillion [roughly US£28.5 billion].

However, this makes little difference to the Kremlin, as the NWF is able to cover this amount several times over.

Russian oil has found its place

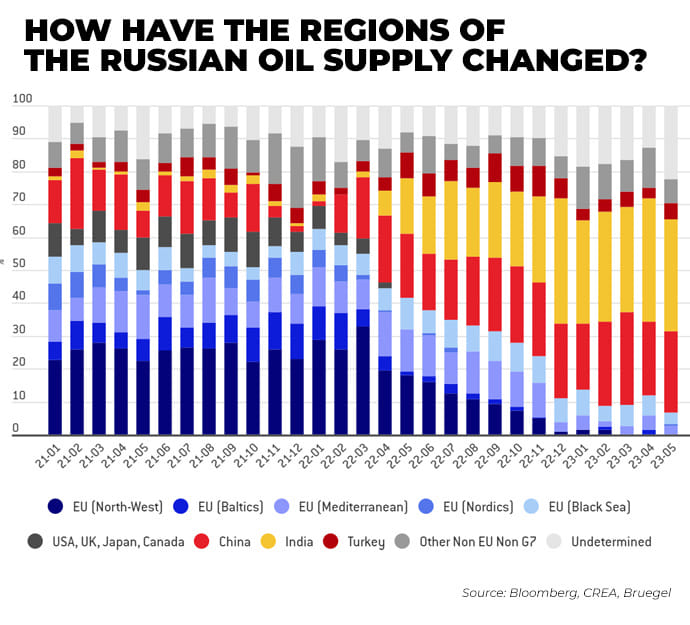

Despite analysts' encouraging forecasts, oil production in Russia has fallen by only 5% since the start of the full-scale invasion. As it turns out, there are still buyers for Russian crude oil. Russia was looking for new customers throughout 2022, before the G7 embargo came into force.

This led to a partial shift in markets: Russian oil moved from Europe to Asia, and Middle Eastern black gold flowed from Asia to Europe.

This shift has taken a toll on Russia. Oil delivery times from some ports have tripled, and logistics costs have risen. Oil has to be sold at a discount in order to drive out competitors and compensate customers for the risks associated with sanctions.

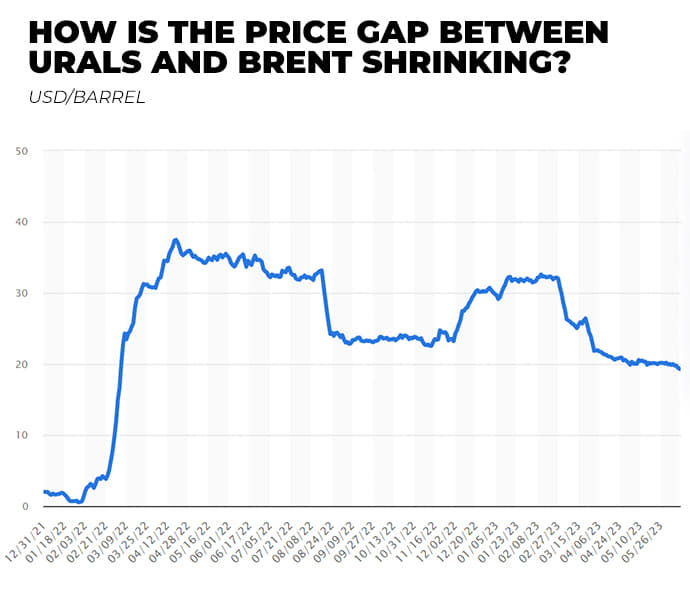

Russian Urals oil [the reference oil brand used as a basis for pricing - ed.] has been sold at a discount below the Brent benchmark since the beginning of the invasion. This discount, of US£20-30 per barrel, has prevented Russia from generating tens of billions of additional US dollars during the war against Ukraine. Western politicians hoped that global oil prices would soon fall and that the price of Urals oil would drop even further, driving the Russian budget into a deep deficit.

However, the reality turned out to be quite different. The deeper Russian oil penetrates the Asian market, the lower the discount below Brent becomes. It was US£37 per barrel at the beginning of the invasion, and now it is £19.

The gap has narrowed by 40% over the past five months.

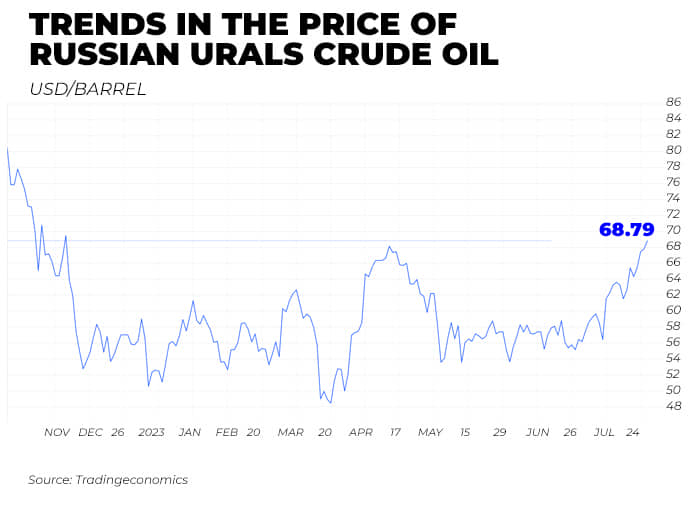

Global oil prices are not going down, since Saudi Arabia is artificially reducing oil production and keeping oil prices high. The rise in global prices, along with the reduction in the discount, has led to a 35% rise in the price of a barrel of Urals oil since March 2023. The average price of Russian oil is now US£67 per barrel.

This is effectively a return to December 2022 levels, before oil sanctions were in place.

This leads to another problem: Russia is increasingly selling oil above a price cap that was introduced in the winter. The new rules deprive tankers of Western insurance policies, should the price of oil from Russia in a contract exceed US£60 per barrel. Therefore, the G7 countries have sought to maintain access to Russian oil while preventing the Kremlin from profiting from it.

However, over the past year and a half, Russia has created a shadow tanker fleet of 15-year-old vessels, insured by dubious companies or by the Russian state or its partners. This fleet is able to transport oil, bypassing Western restrictions. The Kyiv School of Economics (KSE) estimates that Russia is capable of transporting half of its crude oil and a third of its petroleum products via this method.

"It's quite possible that Western transport companies legally transport some of the Russian oil at the permitted price, while the rest is transported by the shadow fleet in roundabout ways at higher prices," KSE analyst Borys Dodonov told EP. He said price caps apply only to vessels leaving Russian ports. If the Russians should resell their oil in the Black Sea to another trader and transfer the cargo to another ship, that oil would not be subject to sanctions, and the Russian oil will safely sail on to customers.

"The Russians often simply manipulate the price in the documents. For instance, the customer pays three times the amount for transport than is actually spent on logistics. In other words, some of the money goes into the pockets of traders associated with Russian companies, while on paper, the price remains US£60 per barrel," Dodonov said.

The KSE study indicates that since the introduction of the price cap, 16% of Russian oil has been sold for more than US£60 per barrel. The picture is even more complicated when it comes to oil products. Petrol, diesel and other premium fuels are subject to a cap of US£100 per barrel.

The market price has not risen above this threshold over the past few months. This means that Russia has not lost anything as a result of this price cap. Loopholes in the sanctions made it possible to ignore price caps and the embargo imposed in the winter by the G7 countries.

The Black Sea Studies Institute and the Blackseanews monitoring group found that European companies are systematically importing Russian crude oil and oil products. The group has identified 40 tankers that violate the crude oil embargo and 67 tankers that violate the oil product embargo since the beginning of 2023. Dodonov believes it is possible to close all these loopholes in the sanctions.

To begin with, he argues that the price cap for oil and oil products should be lowered. The KSE estimates that reducing the price of Russian oil by just US£10 per barrel would deprive the aggressor of US£10 billion in annual revenue. The price cap mechanism must be made to work.

Dodonov believes that the G7 countries are not monitoring market players closely, although they should be conducting investigations, especially of newly created companies transporting Russian oil. This should go hand in hand with stricter requirements for submitting documentation on contracts with Russia. Sanctions against violators of the mechanism should be harsher, including asset freezing and a ban on transporting any oil worldwide.

The West should eventually ban the unsafe passage of obsolete 15-year-old tankers, which mainly carry Russian oil through the [Bosphorus and Dardanelles] straits.

Gas isn't sanctioned

The Russians don't even need to circumvent gas sanctions, because there are practically none. LNG from the United States overtook Russian pipeline gas in deliveries to Europe for the first time in 2022. However, this resulted from Russia's decision to cut supplies.

The European Union began looking for alternatives, building LNG terminals and filling gas storage facilities. There has been some success in doing so, but the EU still needs 30 billion cubic metres of gas per year to get through the winter. It will be imported from Russia.

Russia is leaving operational the TurkStream gas pipeline, the Ukrainian gas transmission system, and LNG terminals through which natural gas is delivered to the EU.

A study by the ANTS National Interests Advocacy Network estimates that at the current rate, Russia is expected to supply 26.5 billion cubic metres of gas to the EU in 2023. This figure is five times less than the volumes before the invasion, but the average price has since increased. Consequently, Gazprom, a Russian state-owned multinational energy corporation, is able to replenish the Russian treasury by RUB 100-150 billion [roughly US£ 1,1-1,6 billion] monthly.

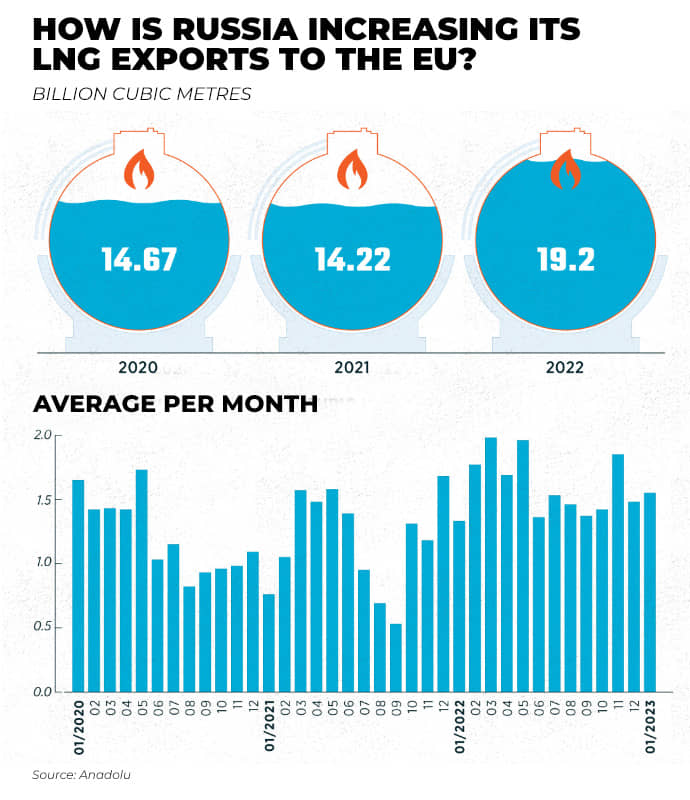

Even if the pipeline supply should eventually stops, Russia will still have significant capacity to export LNG, available for delivery anywhere worldwide. Reuters reports that Russia sold 45 billion cubic metres of LNG in 2022, half of which went to European ports. This is 20% more than in 2021. Going forward, Russia plans to increase the capacity of its LNG terminals and become the world's fourth-largest exporter.

"Global consumption of natural gas is on the rise, and it will soon take second place after oil on the list of the energy sources in highest demand.

It is considered relatively environmentally friendly and easier to use than other fossil fuels. Natural gas is also an essential commodity for the production of plastics and fertilisers, the demand for which is constantly growing. Russian gas will remain in demand across all markets to which it can be delivered.

Therefore, we should not assume that the decrease in natural gas imports from Russia is irreversible," Professor of Economics Oleh Karii told EP. Should Western countries fail to enforce the ban on Russian gas and tighten restrictions on Russian oil, sooner or later Russian supplies will re-enter the market via roundabout routes, nullifying all the progress made over the past year and a half. This article was written as part of an ANTS project titled Russian Assets as a Source of Recovery of the Ukrainian Economy, implemented in cooperation with the National Democratic Institute (NDI) and with financial support from the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

By Bohdan Miroshnychenko, Ekonomichna Pravda

Translation: Artem Yakymyshyn

Editing: Monica Sandor